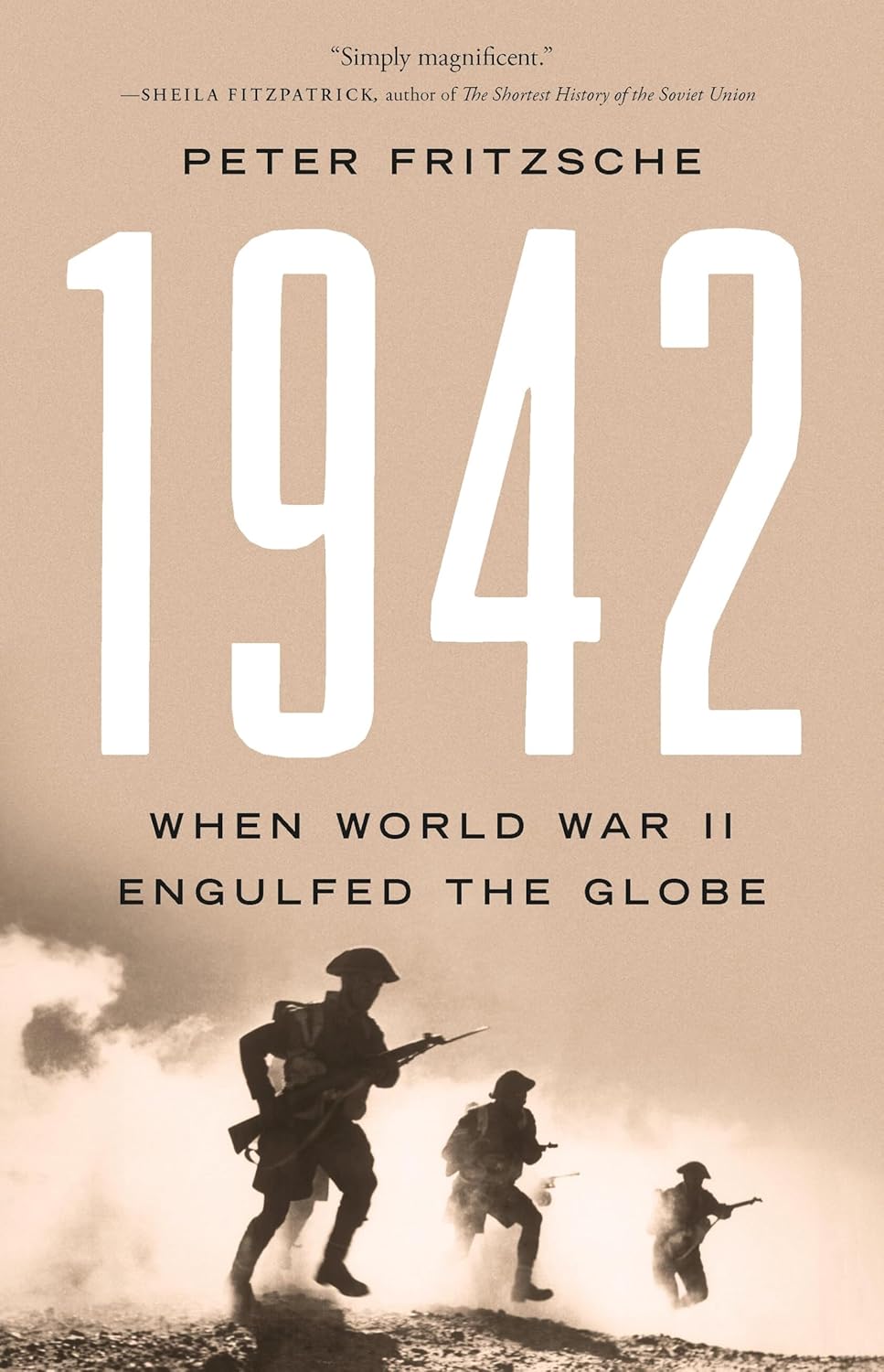

1942: When World War II Engulfed the Globe

- By Peter Fritzsche

- Basic Books

- 576 pp.

- Reviewed by Eugene L. Meyer

- October 23, 2025

Why WWII’s second full year was truly an annus horribilis.

For many authors of nonfiction history, a year is a peg, a convenient device to declare a period of importance, even a turning point — and what more important time in recent memory than the years that framed the Second World War?

But which year? Consider: 1940: The Last Act: The Story of the British Forces in France after Dunkirk by Basil Karslake; 1941: The Year Germany Lost the War by Andrew Nagorski; and June 1944 by H.P. Willmott.

Now along comes Peter Fritzsche’s 1942: When World War II Engulfed the Globe. Whereas other year-themed books focus on military campaigns, decisive battles, and larger-than-life heroes and villains, historian Fritzsche uses 1942 as a starting point. It was, he writes, when the entire planet became fully engulfed in a conflagration on a scale never before seen. In this sweeping, ambitious book, he reframes “the good war,” as it was subsequently called (and almost fondly remembered), at least on these shores.

However, he writes, the idea of “our war” and the “people’s war” left out groups who were “abandoned, denationalized and demilitarized.” America, he notes, was also at war with itself over race, as African American soldiers were called upon to defend the kind of democracy they lacked at home. There is, then, this glaring contradiction:

“The war compressed and hardened existing social patterns even as it popularized and amplified democratic messages.”

This is a serious work that uses a wide lens to capture the big picture while homing in on stories too often lost in our patriotic popular culture. 1942 seeks to illuminate the lives of individuals and families, both on the home front and on the front lines. Thus, we have the relatable letters an everyday German soldier sent to his parents before dying on the Eastern Front. And we suffer with a Ukrainian Jewish family as it struggles to survive famine, virulent antisemitism, and executions.

A professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and the author of several other works on Nazi Germany, Fritzsche uses geography to good effect. Though all the world’s a stage, the war played out in European and Pacific theaters. But the play’s the thing. By his own description, 1942 is more about “the world at war than it is about the provisional victory known as World War II.” He then adds, almost parenthetically, “Thank goodness the Allies won.” It seems curious, too, that Fritzsche suggests anti-communism “motivated Axis aggression in the first place,” when much of what he writes argues otherwise.

Recognizing Japan and Germany as the aggressors, he recounts that citizens of both swore allegiance not as much to the nation as to its leader: Emperor Hirohito and Adolf Hitler, respectively. But there is more to distinguish the two countries that united with Italy to comprise the Axis Powers.

He ably presents the case for Japanese advances. Beyond establishing a so-called Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, the Japanese waged an anti-colonial war against the Western nations that had established empires they called “possessions” in Southeast Asia and the Pacific — from the British in Singapore and Malaya to the French in Indochina, the Dutch in Indonesia, and the United States in the Philippines. Whether the subject peoples wanted to be “liberated” is another question; the war was fought, Fritzsche writes, “to occupy space.”

None of this is to excuse such murderous excesses as the Japanese 1937 Rape of Nanking, responsible for 130,000 deaths, or other aggressive actions Japan undertook, including the attack on Pearl Harbor, arguably provoked by America’s decision to cut off its oil spigots, which Japan needed to carry out its own expansionist, allegedly anti-colonialist aims.

But what separated German from Japanese aggression, Fritzsche states, was the former’s emphasis on race. If Japan was seeking to expand its economic sphere, the German goal was to ethnically cleanse whole countries to make more room (“lebensraum”) for Aryans. It was Hitler’s own “great replacement” theory, and it was grounded in the notion that German blood was superior to all others. Yet the unparalleled Nazi barbarism — embodied by the Holocaust — was minimized by the Allies in their narrative during the war, which they sought to win without such inconvenient distractions as the slaughter of 6 million Jews.

Still, by 1942, the world had learned “of the German efforts to murder Jewish families,” Fritzsche writes, “but other horrors endured by civilian populations such as bombardment, evacuation, forced labor, and famine remained largely unseen in the reporting of the war. Because they did not fit into the militant picture of the war between the Allies and the Axis.”

Phrases like “the winds of war” or “the good war” tend to elide the non-military mass deaths — more than 70 million, mostly civilians — and dislocation of millions of refugees on an unprecedented scale. The well-known execution of citizens in Lidice, Czechoslovakia, after resistance fighters there killed high-ranking Nazi official Reinhard Heydrich, received a great deal of press and overshadowed much larger massacres inflicted in both Europe and Asia.

The author concludes on a curious note. “The experiences of 1942,” he asserts, are “relevant to any estimation of global dangers to social and political life today.” Whether or not that particular year merits such grand projections into our time, 1942 is a worthy consideration of a world gone mad.

Eugene L. Meyer, a member of the board of the Independent, is a journalist and author of, among other books, Five for Freedom: The African American Soldiers in John Brown’s Army and Hidden Maryland: In Search of America in Miniature. Meyer has been featured in the Biographers International Organization’s podcast series.