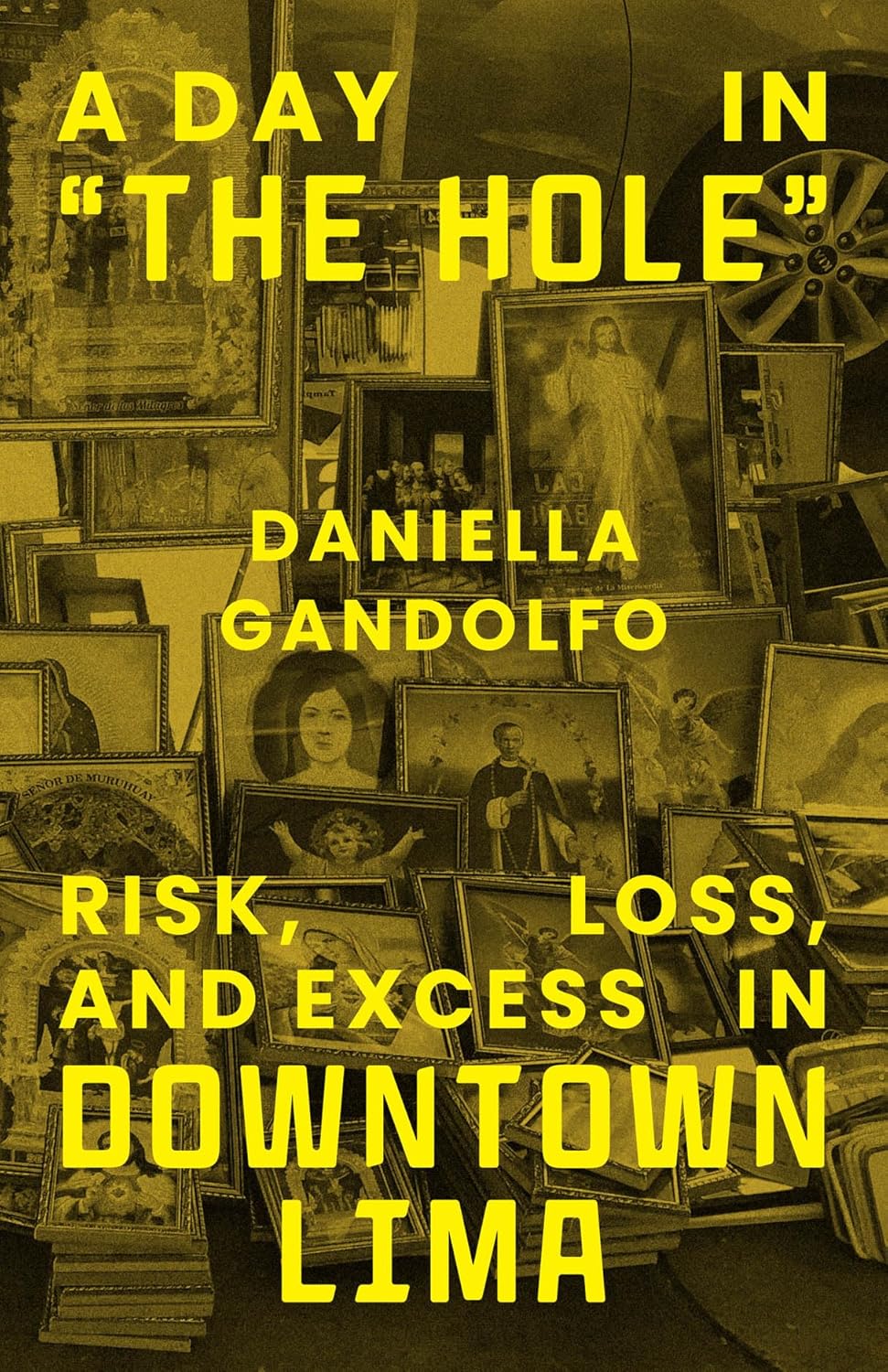

A Day in “The Hole”: Risk, Loss, and Excess in Downtown Lima

- By Daniella Gandolfo

- University of Chicago Press

- 194 pp.

- Reviewed by Cara Tallo

- January 5, 2026

Chaos and commerce thrive in the Peruvian capital.

The Cambridge Dictionary defines a hole as “an empty space.” But while the capitalist chaos of El Hueco, the market at the center of Daniella Gandolfo’s latest anthropological excursion, A Day in “The Hole”: Risk, Loss, and Excess in Downtown Lima, exists on the abandoned foundation of a would-be high-rise, it’s anything but empty.

From the beginning, Gandolfo, a Lima native, grounds the reader in the visual of two office towers, both planned for construction on neighboring corners in the Peruvian capital’s downtown during the urban-planning boom of the mid-20th century. One was erected; the other was left a nascent slab, waylaid by disagreements and bureaucracy.

The tower that was built now houses the country’s Superior Court, ironic given these offices overlook the footprint of the planned second tower, where vendors at El Hueco (which literally translates to “the hole”) regularly flout official rules in the name of efficiency, profit, and survival. This tension — the physical and philosophical structure of the court building versus “Hueco’s hole and squalid building” which “refuses to be reduced” to the forms and checkboxes of bureaucracy — is one in a series of dichotomies that Gandolfo lays bare over the course of the book.

Another comparison of opposites: El Hueco and the neighboring collection of vendors in Mesa Redonda are part of Lima’s historic downtown, declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1991. These markets are linchpins of the city’s informal economy, but their largely unregulated, overcrowded spaces are prone to deadly fires and illegal trafficking. As Gandolfo puts it, these teeming spaces do “not just scoff at Lima’s heritage,” they keep it “on the brink of obliteration.”

Throughout the book, Gandolfo works to help the reader discard traditional capitalistic expectations around how a market like El Hueco “should” work — centering “state regulations and their infractions” — to understand the messy realities of how it actually works. Vendors man tiny stalls for long hours and “expose themselves not just to eviction and merchandise seizures” by city officials punishing those without proper licenses, but also to “mafias” promising protection from those same officials. Together, they push “the logic of capitalism to its very limits,” writes Gandolfo, “often putting everything on the line for short-term gains,” which can be significant. When a large portion of Mesa Redonda shut down for several weeks after a fire, the estimated losses were around $420 million, or $20 million a day.

The “Day” Gandolfo refers to in her title is one August 24th, as the vendors of El Hueco gather to celebrate the 34th anniversary of their cooperative organization. On this day, as Gandolfo enters the sunken market, there’s blaring music and balloon decorations for the occasion, while a “blue translucent nylon tarp” acts as a makeshift roof to protect against the winter drizzle. She uses the event to introduce us to a number of colorful vendors at the market, as well as to an even more transcendent character: the Lord of Miracles. At first appearing as a sort of “patron saint” of El Hueco, it becomes clear that this large image — with its ties to “Indigenous and African forms of praise and worship that were historically repressed as idolatrous and defiant” — has become a modern symbol of resistance to state-sponsored urbanization efforts.

Before sitting down to write, Gandolfo observed life in and around El Hueco for the better part of a decade. Over that period, she sees a community that is alternately celebratory and corrupt, both believing in a future where the 1,500-odd members of El Hueco’s co-op organize to build a safer facility and unsure of what tomorrow will bring.

There are no easy answers in this exploration, but that is by design. Weaving the work of economists, philosophers, and fellow anthropologists, Gandolfo makes the case for El Hueco as a nexus of strategic resistance to traditional capitalism, which respects and rewards a privileged few. El Hueco and its vendor cooperative operate with a fluidity that can feel foreign and uncomfortable juxtaposed with the machine of global capitalism, where linear progress is recognized as a marker of modernity.

The Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines a hole as “an opening,” leaning into the potential of an undefined space rather than emphasizing its absence of structure. This feels more apt in the case of El Hueco given the dynamic backgrounds of the characters at the market in particular and in Lima as a whole.

Gandolfo’s work is a heady but thought-provoking interrogation of the complexities of building economies and communities in any city. While there’s no magic formula for balancing the many competing interests in a such a venture, as she writes, “Lima’s markets are still a source for Peruvians’ imagination of alternatives to the social order even if we don’t yet know exactly what these alternatives are.”

Cara Tallo is the former executive producer of NPR’s “All Things Considered,” “Invisibilia,” and “Morning Edition.” She’s currently pursuing her MFA at American University while freelancing at MakingitWork.io.