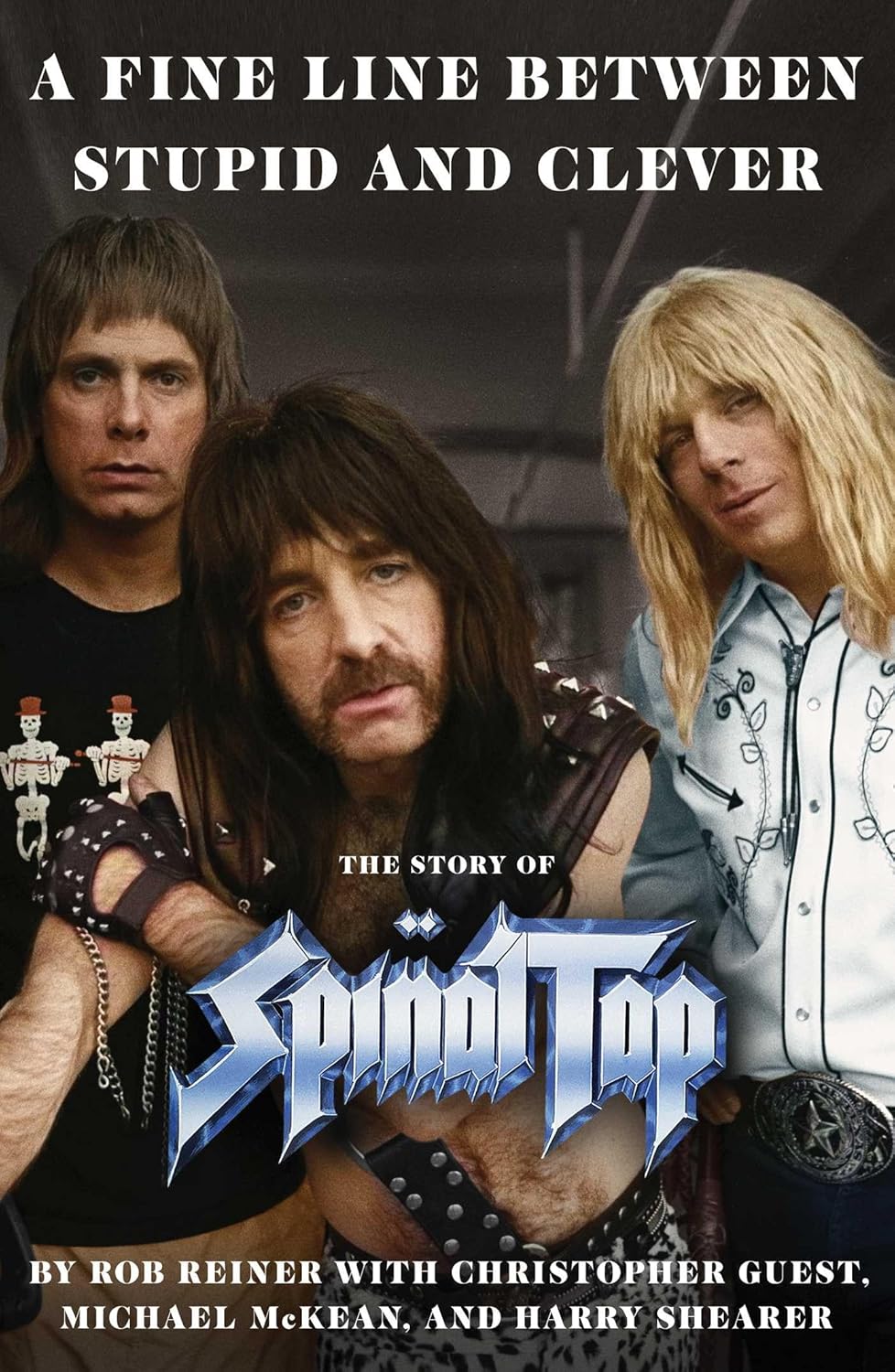

A Fine Line Between Stupid and Clever: The Story of Spinal Tap

- By Rob Reiner with Christopher Guest, Michael McKean, and Harry Shearer

- Gallery Books

- 288 pp.

- Reviewed by Daniel de Visé

- September 15, 2025

What’s wrong with being sexy?

“This Is Spinal Tap” feels like the ultimate cult film: powerfully appealing to a select group of fans, baffling to everyone else. Studio executives found Rob Reiner’s 1984 “mockumentary” utterly unfunny. Test screenings in Dallas and Seattle were disastrous. Many theatergoers thought it was a serious documentary about a real band. Either you got the joke or you didn’t.

In fact, the jokes in “This Is Spinal Tap” weren’t really jokes. The humor was deadpan, and I suppose it was subtle, although I can’t imagine not laughing at it. Perhaps you needed some working knowledge of Yoko and the Beatles to find something funny in the overreaching band girlfriend who mispronounces “Dolby.” Maybe only Yardbirds fans got the merciless British Invasion parody “Gimme Some Money” and spotted the Jeff Beck pageboy mop atop Nigel Tufnel’s head. And maybe you had to be in a band yourself to grasp the ignominy of taking second billing to a puppet show on an amusement-park stage.

But we music heads love “This Is Spinal Tap.” We’ve spent decades wondering at the specific source of every shot in the film. Was the song “Stonehenge” a sendup of Led Zeppelin at its most pompous and Tolkienesque? Which real-life band lost the most drummers to bizarre gardening accidents? Did any actual bass player ever get trapped onstage inside a giant plastic pod?

Now, at last, we have answers tucked within the pages of A Fine Line Between Stupid and Clever: The Story of Spinal Tap, penned by Reiner, the film’s director, with help from his fellow screenwriters (and the movie’s stars) Christopher Guest, Michael McKean, and Harry Shearer.

I read the book in an afternoon. My copy ran to fewer than 200 pages, not counting a faux, 60-page oral history that’s printed upside-down and backward at the end. (A B-side. Har.)

It was fascinating and depressing to learn how hard Reiner and company labored to convince anyone to make the film. How could so many aging studio execs have failed to find it funny? I guess you have to consider that it came together more than 40 years ago and to imagine how all that rock ‘n’ roll humor might’ve come off to someone old enough to have missed the whole arena-rock era. Even now, I suppose, you could find cinema patrons who have no reference point for the “Big Bottom” bassline, canker sores, or “Hello, Cleveland!”

The concept for “This Is Spinal Tap,” I can now reveal, began as a satiric mashup of “The Last Waltz,” Martin Scorsese’s cinematic farewell to the Band; “The Song Remains the Same,” Led Zeppelin’s cheesy-but-righteous concert film; “The Kids Are Alright,” the aerobic Who documentary; and “Don’t Look Back,” D.A. Pennebaker’s Bob Dylan doc.

Reiner and his co-writers had a gift for “schnadling,” a term evidently coined by Guest, which means settling into character and improvising stuff. Guest, in my mind, was the pivotal player in the project. He came out of National Lampoon, and for much of the 1970s, he and various collaborators had been writing and performing parody songs, first for “Lemmings,” the off-Broadway sendup of Woodstock, and later for the “National Lampoon Radio Hour” and a series of long-playing Lampoon records. Guest did a killer Dylan impression and a brilliant James Taylor. On the 1975 Lampoon album “Good-bye Pop,” he rolled out a Cockney accent, the template for Tufnel.

Spinal Tap, the band, first performed in 1979, on a network pilot titled “The T.V. Show,” in a sketch that parodied the old “Midnight Special.” Reiner played deejay Wolfman Jack. “This Is Spinal Tap,” the film, came together as a collection of funny ideas on index cards. Guest had once watched a British rocker stroll into a Bleecker Street guitar store with a prominent bulge in his crotch that later slipped to his ankle. Shearer remembered a promoter who prostrated himself after a dreadful convention show, beseeching the performers, “I’m not asking you, I’m telling you: Kick my ass.” Reiner had written a sketch with actor Bruno Kirby about a limo driver with a Sinatra obsession. All of those bits went on cards.

McKean’s lead-singer character, David St. Hubbins, was modeled on the blond-tressed ‘70s idol Peter Frampton. Shearer’s mustachioed bassist Derek Smalls was the quintessential “quiet one,” based on softspoken rock bassists John Entwistle and Bill Wyman, but with an onstage alter ego drawn from the S&M stylings of Judas Priest. And Reiner’s Marty DiBergi channeled Scorsese.

To prepare for the movie, Shearer embedded with a real touring hard-rock band, Saxon, taking copious notes. And he, McKean, and Guest all went backstage at an AC/DC show and saw how much of it really was a show. “Like, they had a huge wall of Marshall amps,” Guest recalled, “but if you walked behind them, they were not all plugged in.”

The umlaut over the “n” in Spinal Tap, which my computer refuses to print (probably because the letter doesn’t exist), was a nod to Motörhead and Blue Öyster Cult.

There never was a proper script for “This Is Spinal Tap,” just a rough treatment and a 20-minute reel that Reiner assembled featuring some of the best bits. None of the studios liked it. But pirated copies made the rounds in Hollywood, and some of them reached an appreciative audience. Reiner heard that one was found in the Chateau Marmont bungalow where John Belushi died.

Reiner shot the film as a series of improvised scenes based on the funny ideas on the index cards. Most of its immortal lines — “These go to eleven”; “You can’t really dust for vomit”; “It’s such a fine line between stupid and clever” — were apparently unscripted. Music videos depicted Tap’s past incarnations, first as a Yardbirds-style blues-rock band and later as a flower-power hippie band. DiBergi followed Tap on its ill-fated U.S. tour, although that footage, and indeed the entire movie, was actually shot in Los Angeles.

Even as the film came together, ideas continued to trickle in from real life. The writers read a Rolling Stone article about Van Halen and its absurd contract rider, which forbade brown M&Ms backstage. And Guest attended a Shakespeare production in Central Park where the wireless mics malfunctioned, broadcasting taxicab calls over the loudspeakers as the actors froze.

As Reiner relates it, “This Is Spinal Tap” opened on March 2, 1984, to small and mostly befuddled audiences. But the critics got it. In the weeks and months that followed, music heads found their way to theaters. Musicians, of course, loved it even more. For years after its release, it played on VCRs in tour buses across the nation.

A Fine Line Between Stupid and Clever is a cult book about a cult film. If you’re in the cult, you know who you are. Enough of my yakkin’.

Daniel de Visé is the author of five books, including The Blues Brothers: An Epic Friendship, the Rise of Improv, and the Making of an American Film Classic.