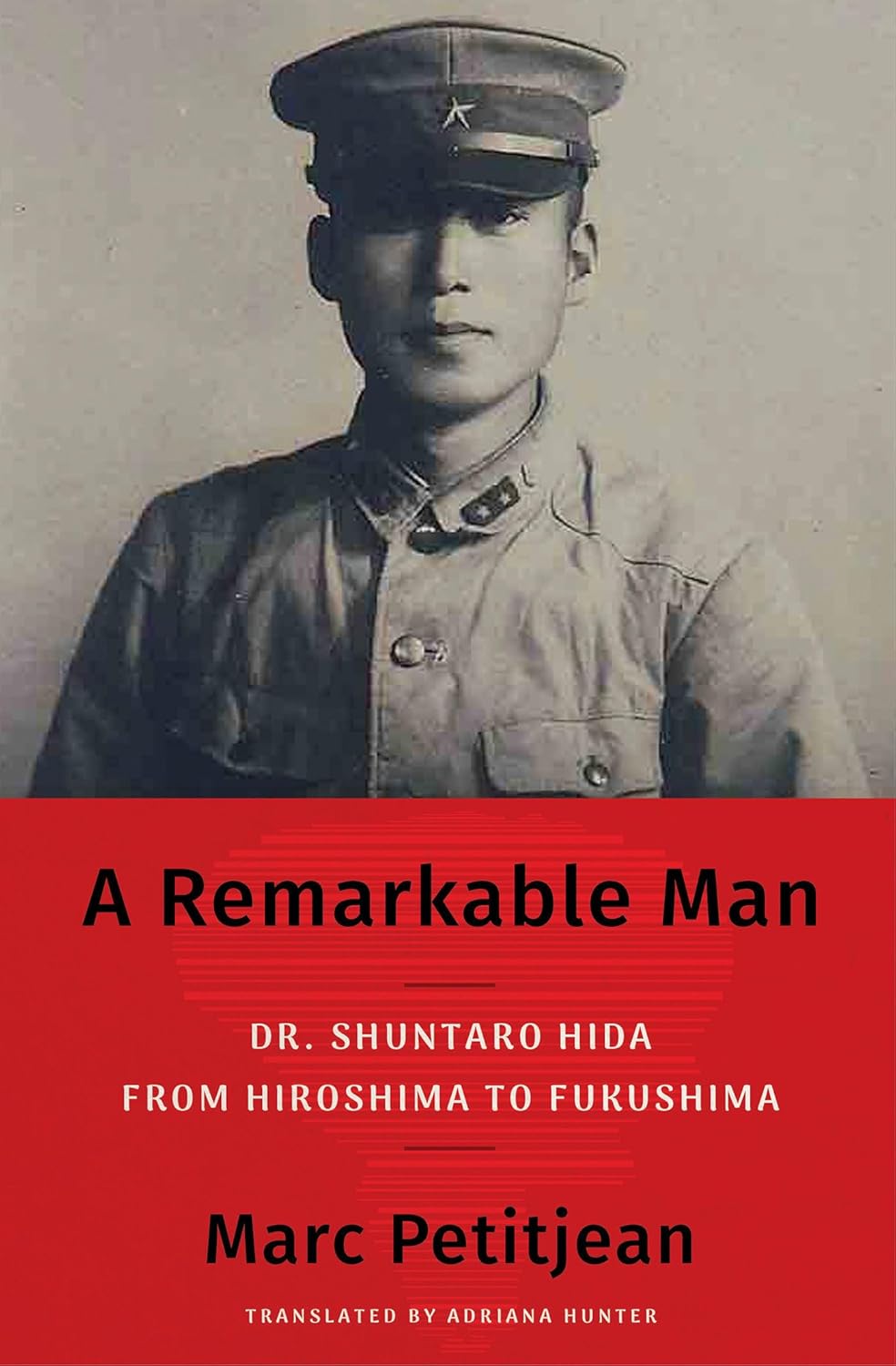

A Remarkable Man: Dr. Shuntaro Hida from Hiroshima to Fukushima

- By Marc Petitjean; translated by Adriana Hunter

- Other Press

- 192 pp.

- Reviewed by Alice Stephens

- July 24, 2025

A physician and atom-bomb survivor exposes the truth about radiation poisoning.

On August 6, 1945, a young doctor was seven kilometers from ground zero when the atomic bomb detonated over Hiroshima. As told in Marc Petitjean’s A Remarkable Man: Dr. Shuntaro Hida from Hiroshima to Fukushima, the man rushed toward the mushroom cloud against a tide of fleeing victims, so many of them that he had to wade in the river rather than go through the crowd.

“Those who were still alive moved or moaned. Cried for help. I felt I was being put to a test as a human being. If I’d let myself scream then, I would have gone mad. And it all would have been over. But on the threshold of madness…how can I put this? I resisted.”

The young man, Shuntaro Hida, had been rushed through his medical training in order to become a military doctor during the final years of World War II. Posted at Hiroshima’s military hospital, Dr. Hida, following Japan’s surrender, tended to the hibakusha, as atomic-bomb victims are known in that country, learning from their conditions and symptoms about the effects of radiation on the human body. Thus began a lifelong mission to study, treat, and educate others about radiation sickness.

It was an uphill battle. The biggest obstacle was the American government. According to the author, the U.S. did not want the world to see the horrific human toll of the atomic bomb. When the first American troops arrived in Japan a month after the bombing, they assured the Japanese that there was no threat from radiation. According to Dr. Hida, Douglas MacArthur, appointed governor of Japan by President Harry S. Truman, “said that the atomic bomb was an American weapon classified as a defense secret, which meant that all information relating to the atomic bomb was protected. This included the effects of radioactivity on victims.” Doctors were not allowed to keep written records on their patients, nor to do research.

Furthermore, when bomb victims sought medical help from the Americans, “instead of being treated, they were examined and studied like guinea pigs. The American government had given orders not to tend to the hibakusha’s wounds or treat their conditions because they didn’t want anyone thinking they regretted what they’d done or were apologizing for using the bomb.”

Dr. Hida asserted the reason behind this obfuscation was that if news of the effects of residual radiation came out, it “might threaten the civil nuclear power program that the United States intended to develop and export.”

From his long experience of observing and treating radiation sickness, Dr. Hida concluded that radiation from the bombs lingered and spread far from the explosion sites by weather and other natural forces, contaminating the air, land, and water and showing up in crops, animals, and by-products consumed by the public. Working against the official narrative of governments and power companies, he continued to alert the world to the dangers of radiation until his death in 2017.

His task became more urgent in 2011, when a major earthquake caused a catastrophic tsunami to flood Japan’s Fukushima Daiichi Power Plant, releasing radiation into the environment in the second-worst nuclear accident after Chernobyl. Following that incident, according to the author, the Japanese government engaged in a misinformation campaign to minimize the effects of radiation:

“A map of contamination across Japan was circulated, then swiftly altered. There was no point unnecessarily panicking the population. Neither should they give credence to the idea that radioactive pollution could spread hundreds of kilometers from the site, as it had with Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The Japanese government was prepared to do anything to prove that radioactivity was innocuous; one politician, Yasuhiro Sonoda, even went so far as to be filmed drinking water from a nuclear reactor cooler.”

The author first met Dr. Hida in 2005 when he filmed the documentary “Atomic Wounds,” about the then-88-year-old crusader’s long career as an advocate for radiation patients and opponent of nuclear power. When the Fukushima accident happened, Dr. Hida was 94, yet he continued to advise victims of radiation, lecture, give interviews, and gather data.

This slim volume, originally published in French and adeptly translated by Adriana Hunter, is largely comprised of Dr. Hida’s own words excerpted from Petitjean’s interviews, with the author providing background information and historical context. Petitjean doesn’t pretend to be impartial, writing with immense admiration for Dr. Hida’s lifelong dedication to the hibakusha and his brave opposition to powerful governments in warning an oblivious world about the dangers of radiation.

As nuclear energy is being embraced by more countries, nuclear arms proliferate, and wars rampage across the globe, the world must heed the voices of Dr. Hida and the hibakusha. In 2024, the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to Nihon Hidankyo, an association of hibakusha who advocate for the rights of bomb survivors — a demographic who not only survived unimaginable physical and mental suffering, but are today pariahs in Japan, shunned and discriminated against — and strive for a world free of nuclear weapons. Now, the rest of the world needs to catch up.

Alice Stephens once lived in Nagasaki, where people still leave bottles of water in the streets for the bomb victims, many of whom died begging for water. She believes it is a war crime to use nuclear arms and fervently hopes it will never happen again.