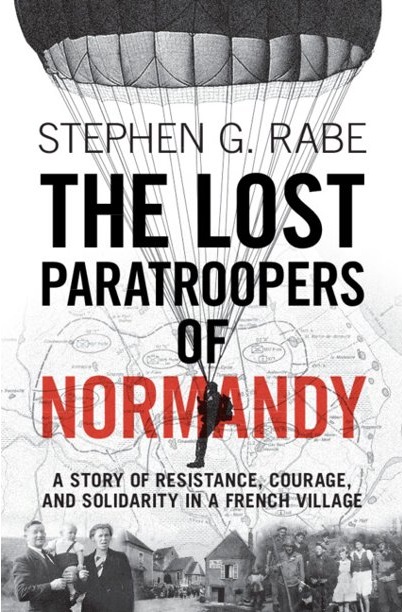

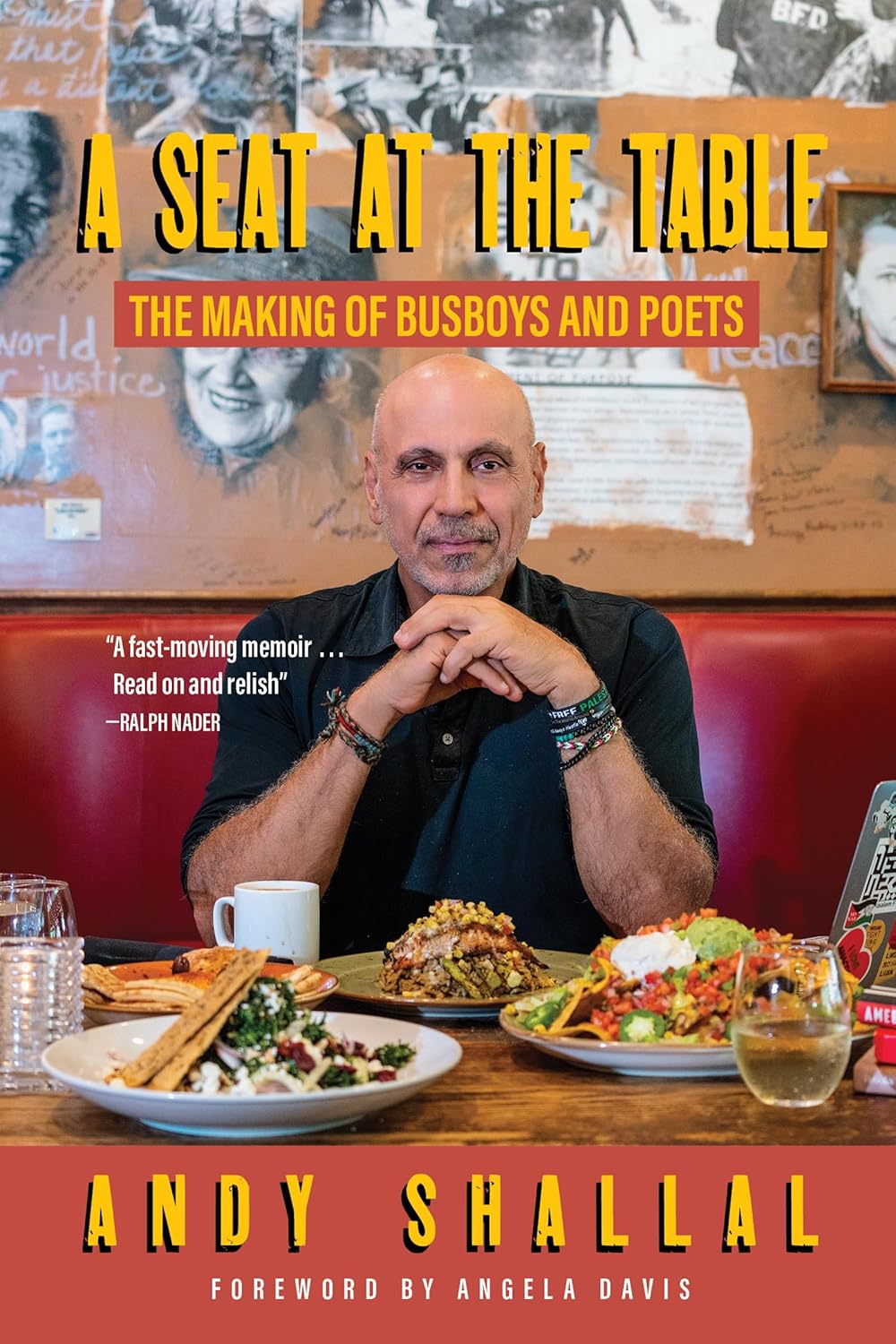

A Seat at the Table: The Making of Busboys and Poets

- By Andy Shallal

- OR Books

- 224 pp.

- Reviewed by William Rice

- September 23, 2025

The activist founder of a DC fixture shares how it all began.

Television’s “The Bear” depicts restaurant management as so stressful that it’s almost taken away this viewer’s appetite for dining out. Some of that same struggle is described in Andy Shallal’s new memoir, A Seat at the Table, but in this account, the joys of the hospitality industry far outweigh the costs — especially when left-wing politics is stirred into the pot.

Shallal is the founder and owner of Busboys and Poets, the combination restaurant, bookstore, and performance space that’s been feeding Washington, DC, bodies, minds, and souls for 20 years now. It began at 14th and V streets in Northwest, but there are today eight locations throughout the core metropolitan area. Anyone in the DMV even vaguely associated with liberal causes has probably been to an author reading or other presentation at a Busboys.

In the book, Shallal displays a radical’s ambivalence about America: big fan of the nation’s ideals, less than excited about its historical follow-through. Like a lot of immigrants and people of color, he has good reasons for his mixed feelings. A Muslim native of Iraq, his experience of the U.S. began as a child with the scatological mispronunciation of his first name, Anas, and continued bumpily thereafter — especially when his birth country and his adopted country were at war.

At a neighborhood gathering soon after 9/11, he resents having to condemn the attacks more roundly than anyone else in order to prove his loyalty, and he rejects the offer of an American flag to display on his property. (When someone places a miniature Stars and Stripes on his mailbox, he takes it down.)

As his success as a restaurateur grows, so does his interest in and support of leftist causes. Shallal was a onetime delegate to the Democratic National Convention and, years later, hosted a ball to celebrate the election of Barack Obama. But his politics generally lie outside the moderate mainstream; his position on the intractable Israel-Palestine issue, for instance, is hardline pro-Palestinian with no apparent doubt or ambivalence. His impressive collection of progressive friends and admirers includes Ralph Nader, Howard Zinn, and Angela Davis (the latter of whom wrote the book’s foreword).

Shallal was introduced to the restaurant business early — when his bookish father wound up the unlikely owner of a pizzeria in Northern Virginia — and the book offers a tasty smorgasbord of culinary descriptions for foodie readers. His depiction of a fancy tofu dish is enough to make a carnivore salivate.

Shallal is the rare small-business owner who’s had a string of successes. His winning record of creating popular eateries is only partially marred by his first solo venture: a casual Mediterranean establishment between Dupont and Logan circles that languished until a favorable review by legendary Washington Post restaurant critic Phyllis Richman saved it.

Shallal tells his brief tale — it’s a small-format book of just under 200 pages — with workmanlike writing: The prose is comfort food, not a gourmet meal. He occasionally hits on a new expression, but in general, busy phones “ring off the hook,” a tough boss is the “Manager from Hell,” and crowded eateries are “bustling.”

In the end, A Seat at the Table is an inspiring story — what used to be called “an American story” before other Western countries became more socially mobile than we are now. An 11-year-old boy from Baghdad lands in the wilds of Northern Virginia in the mid-1960s, and 40 years later, he’s a successful entrepreneur who invents an entirely new space for cultural and civic engagement.

(Not to take away from the accomplishment, but it’s worth noting that the author’s father began in America as U.S. representative of the Arab League, and the Shallals’ living arrangements both here and back in Iraq were always ample and gracious. So, this isn’t exactly an “up from poverty” story.)

Shallal has an unusual and useful perspective on a subject that’s never far from the surface in DC: race. Early in the book, his uncle — who preceded young Anas to the States — worries about how dark his nephew looks when he meets his brother’s family at the airport. The boy tries to straighten his hair. White schoolmates call him the N-word, and Black students ask if he’s a light-skinned “high yellow.”

One discouraging but very human reaction to being mistaken for a disfavored minority is to put as much distance between yourself and that group as possible. Yet Shallal seems never to have done that. He instead became an amateur historian of the Harlem Renaissance (the name Busboys and Poets was inspired by the life and work of Langston Hughes) and opened the first Busboys in the fabled U Street Corridor, the one-time cultural center of Black DC that had fallen on hard times.

Near the end of his memoir, Shallal gives an impromptu private tour of the yet-to-open flagship Busboys to two older Black women who’d been peering in the windows. They seem put off when, in answer to their questions, he announces he’s from Iraq. But when they see the mural he created of famous and should-be-famous civil- and human-rights leaders, the visit ends in a communal hug.

William Rice is a writer for political and policy-advocacy organizations.