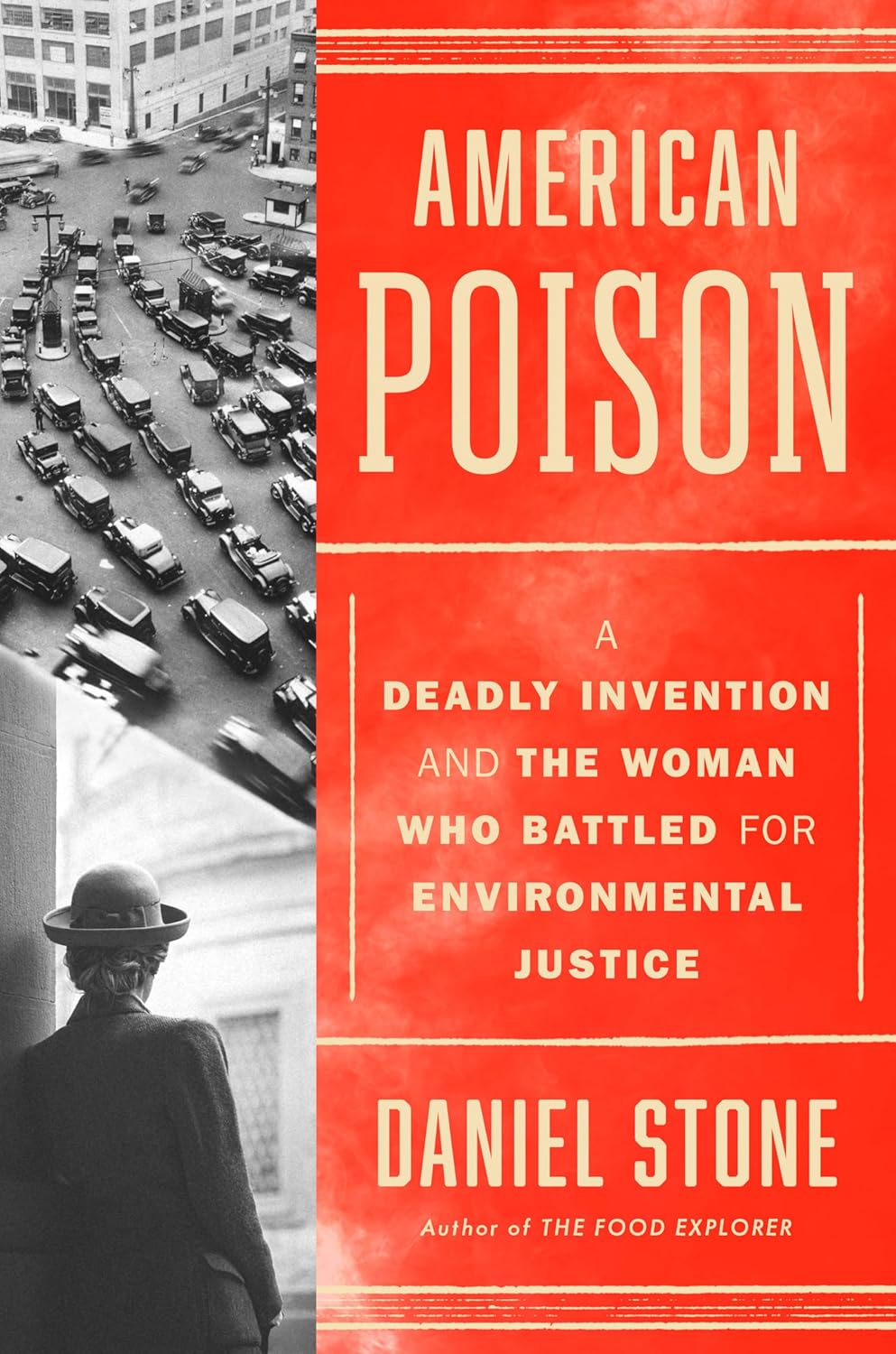

American Poison: A Deadly Invention and the Woman Who Battled for Environmental Justice

- By Daniel Stone

- Dutton

- 368 pp.

- Reviewed by Rose Rankin

- March 12, 2025

A timely tale about corporate whitewashing that contaminated a nation.

It’s frightening to learn the extent of contamination from “forever chemicals” known as PFAS —how nearly every human body carries them in their tissue, every water source brings them into our homes, every product from cookware to clothing is infused with them. It’s also an infuriating example of corporate malfeasance, essentially prioritizing profits over safety.

Yet as Daniel Stone’s American Poison makes clear, PFAS is just another in a long list of dangerous substances that have been spread throughout our environment while enriching their inventors. His subject is tetraethyl lead, better known as leaded gasoline, and the decades-long battle to get it out of our cars. It’s in many ways a disheartening story, but it also proves that change is possible even in the face of entrenched corporate interests.

American Poison centers on Alice Hamilton, a physician and public-health expert whose work from the 1910s through midcentury revealed the colossal amount of safety issues in industrial factories nationwide. Unfairly lost to history, Hamilton was Harvard’s first female faculty member, and she broke barriers as a White House advisor and an acclaimed researcher at a time when few women could obtain any medical training.

Hamilton’s dogged pursuit of evidence-based findings on the chemicals workers were exposed to brought her into direct conflict with Thomas Midgley, the inventor of tetraethyl lead, and his boss, Charles Kettering, who licensed the invention to General Motors (GM) in 1922. Stone weaves together Hamilton’s research and growing clout as a scientist with Midgley’s efforts to discover a fix for “engine knock” in the early 1920s. This was a noisy effect from the incomplete combustion of fuel in the engines of early automobiles, and it prevented cars from reaching high speeds.

As autos took the nation by storm after World War I, solving this engine issue was of prime importance to all car manufacturers, including GM, which worked with Kettering’s laboratory. After many attempts to find a chemical that could combine with gasoline to stop engine knock, Midgley demonstrated that tiny amounts of tetraethyl lead worked perfectly — except that it poisoned him and others who worked with it. He and Kettering were able to keep the noxious effects of “Ethyl gasoline” quiet for a little while, but a grisly poisoning at a GM plant in 1923 alerted the nation to its dangers.

To Hamilton, lead was a well-known industrial toxin that didn’t belong in exhaust fumes, but weak-willed federal officials and an aggressive PR campaign by GM kept leaded gas in the pumps. The book has the feel of a true-crime thriller at times, as Hamilton and other public-health officials search to determine the cause of the hallucinations, violent outbursts, and gruesome deaths happening to workers handling tetraethyl lead. Her research led her to the incontrovertible fact that Ethyl gasoline was a dangerous poison that dispersed lead throughout the air and landscape, putting literally everyone at risk.

The climax for Hamilton came at a 1925 government hearing meant to disclose all the data, both from scientists like herself and from experts hand-picked by the auto industry. But rather than end with a bang, the story whimpered to a close under the weight of depressingly familiar tactics — corporations using compliant scientists to introduce doubt and “debate” about empirical findings; lackadaisical government regulators failing to rein in a profitable industry; and medical experts being sidelined for sharing inconvenient truths. Hamilton herself was barely allowed to speak.

Ethyl gasoline continued to sicken the U.S. and the entire world for another 50 years, with GM and its subsidiary Ethyl Corporation using the playbook later copied by tobacco and oil companies. Writes Stone:

“At the core of their plan was doubt, denial and delay. So long as they could leverage doubt to create a defensible environment of uncertainty, they could stall critical questions.”

Despite her research on tetraethyl lead being ignored, Hamilton went on to live a long and productive life and enjoyed many professional accomplishments. Midgley suffered grievous physical and mental affects from continuous lead poisoning and eventually committed suicide. (But he still made millions from his noxious invention and from his next blockbuster, CFCs, the compounds that caused the ozone hole.) Kettering, meanwhile, remained a celebrated industrialist in spite of his role in covering up the risks of leaded gas.

American Poison isn’t all doom and gloom, though. In fact, Stone remains more positive than many readers (including this reviewer) will. In the 1950s and 1960s, Clair Patterson proved leaded gasoline’s toxicity once again, and public opinion finally shifted, although the invention of the catalytic converter — which mitigated engine knock — also helped turn the tide.

Stone shows that with enough time and improved scientific capabilities, we can actually find safer alternatives to dangerous inventions. But the underhanded tactics, complicit regulators, and limitless greed that caused decades of life-altering lead poisonings nationwide leaves the reader with a sense of exhausted frustration more than hope.

Rose Rankin is a freelance writer from Chicago. She focuses on history, science, and gender issues, in particular, women’s literary history.