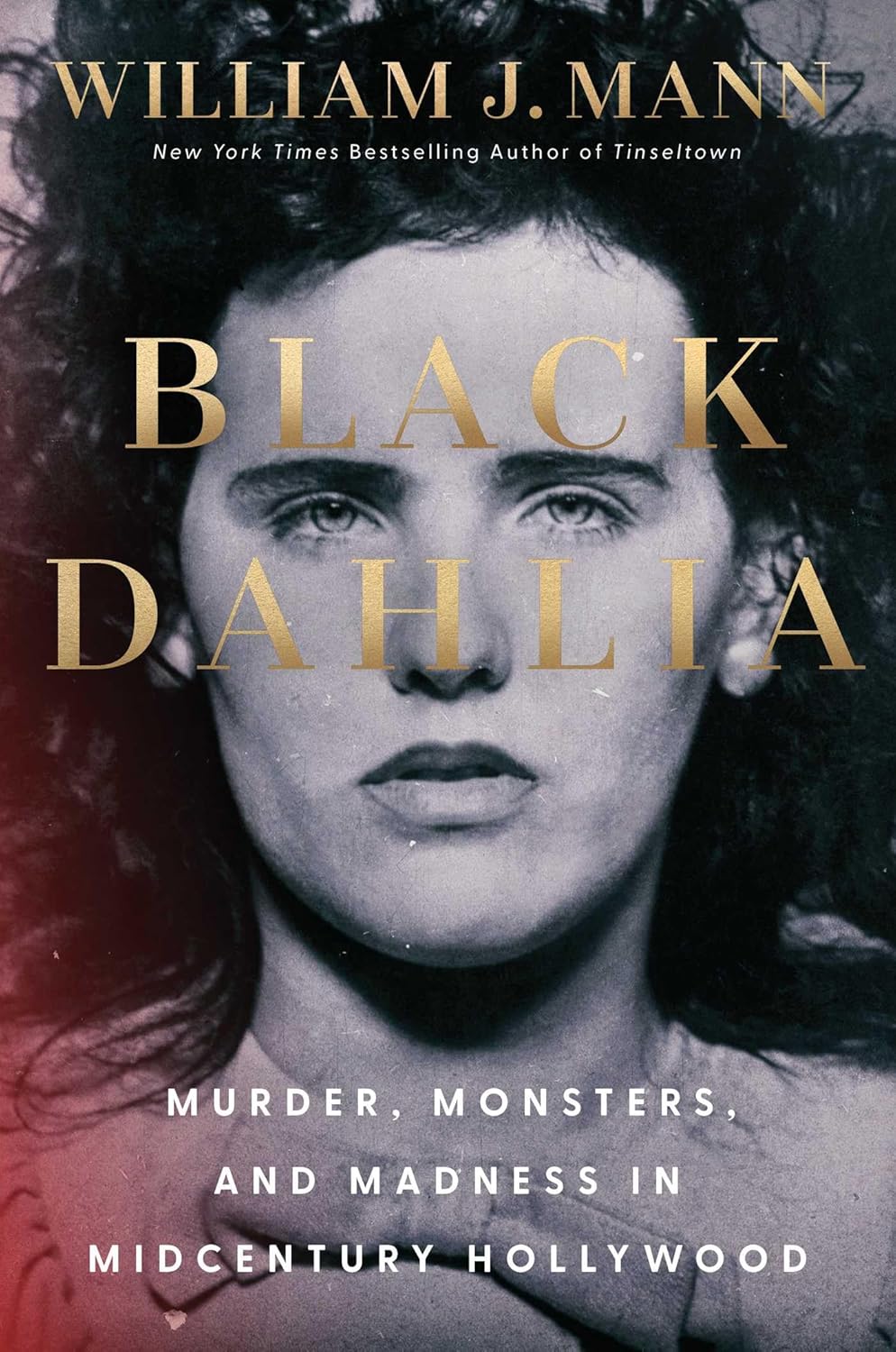

Black Dahlia: Murder, Monsters, and Madness in Midcentury Hollywood

- By William J. Mann

- Simon & Schuster

- 464 pp.

- Reviewed by Diane Kiesel

- February 5, 2026

A stellar recounting of the grisly, 80-year-old cold case.

The nude, mutilated, blood-drained, bisected body of Elizabeth Short (aka “the Black Dahlia”) was dumped on a grassy Los Angeles lot on the frosty morning of January 15, 1947, but she’s never been laid to rest. Novelists, true-crime authors, filmmakers, and internet sleuths have kept her image alive nearly 80 years as they hunt for her killer in this famously unsolved crime.

Professor and prolific author of Hollywood tales William J. Mann joins the crowd with his new book, Black Dahlia. Relying on police reports, the autopsy, contemporary newspaper accounts, FOIA requests, grand-jury transcripts, and interviews, he crafts a solid, entertaining narrative about the brief life and horrible death of the 22-year-old drifter/grifter. But even with his dogged scholarship, Mann has no more idea of who murdered Short than the LAPD homicide squad did the day her body was discovered.

Born July 29, 1924, in Medford, Massachusetts, Elizabeth Short — called “Beth” or “Betty” — was one of thousands of starstruck young women who boarded buses to Tinseltown during World War II, hoping to be “discovered.” She had cascading dark hair and icy blue eyes. Men were fascinated as she pranced by in black skirts, slyly revealing a rose tattoo on her thigh. A drugstore soda jerk said patrons nicknamed her the Black Dahlia because of her wardrobe, the flowers she wore in her hair, and Alan Ladd’s then-popular film noir, “The Blue Dahlia.”

Short’s circumstances were humble. She skipped out of cheap rooming houses without paying the rent, relied on the kindness of strange men for meals, and engaged in do-it-yourself dentistry, filling her rotted teeth with melted candle wax. Despite her dreams of stardom, she did nothing to facilitate a movie career other than wander the streets of Hollywood day and night, alone. In hindsight, it’s not hard to see that the Dahlia’s story might not end well.

Around 50 years ago, coinciding with the unsettling rise in inner-city violent crime, the haunting story of the Dahlia’s demise caught fire in the literary world. Crass crime novelists John Gregory Dunne and James Ellroy were among those mesmerized. Dunne fictionalized her story in his 1977 True Confessions, calling her “the Virgin Tramp.” A decade later, Ellroy, in The Black Dahlia, painted his fictional Short as a “compulsive liar with 100 boyfriends.”

Nonfiction authors, for their part, claim to have solved the crime, sometimes with ludicrous results. Retired L.A. detective Steve Hodel, in Black Dahlia Avenger: The True Story, blamed Short’s murder on his own late father, a doctor who fled the country after being acquitted of sex-abuse charges involving Hodel’s half-sister. Hodel’s conclusion was based, in part, on a photograph he claimed was of the Dahlia buried in the Old Man’s personal effects, although the picture hardly resembles Short.

All of this begs the question: Do we really need another book about the Dahlia? The answer is yes, so long as it’s Mann’s, which captures a defining moment in Los Angeles true-crime lore. His focus in Black Dahlia is less on the killer and more on Short’s final months, appreciating she was both a symbol and victim of her time. Mid-20th-century American men could sow wild oats with impunity, but women who dared to do the same paid a price. (See virtually any episode of “Mad Men.”)

Between July 1946 and her death, Short was involved with no fewer than 18 men, most of them married, some unsavory. Some were one-night stands; none lasted long. Then, for a reason none of the sleuths (professional or otherwise) ever figured out, Short, on December 8, 1946, skipped out of L.A. on an evening bus to San Diego. Once there, she parked herself in an all-night movie theater until usher Dorothy French took pity on her and brought her home for a hot meal and a place to sleep for the night. It turned into a month of nights before French’s mother tossed Short out.

A married traveling salesman she’d met in San Diego, Robert “Red” Manley, drove Short back to L.A. on January 9, 1947, depositing her luggage at the Greyhound bus terminal and Short in the lobby of the posh Biltmore Hotel. He left at about 7 p.m., claiming he never saw her again. The only reliable sighting of the living Dahlia thereafter was by a Biltmore doorman, who saw her leave the hotel alone at 10 p.m. that night. Manley was a prime suspect, but after being sweated under the lights by cops and Los Angeles Herald-Express reporter Agness Underwood (soon to become the first woman city editor of a major newspaper), he was cleared.

Back then, the police and the press were intertwined in a way considered shocking today. Short’s unretrieved suitcase from the Greyhound depot was found by Los Angeles Examiner reporters, and police traveled to the newspaper office to inspect it. The FBI relied on Hearst’s International News Service wirephoto technology to access the deceased’s fingerprint for an identification. And an Examiner reporter, not a detective, informed Short’s mother about the murder. He pretended the Dahlia had won a beauty contest and pumped Mom for details about her daughter’s life. Not until he got what he needed did he reveal the truth.

The investigation was a textbook example of snafus in a high-profile case. LAPD politics led the brass to substitute the loose cannons of the Gangster squad for experienced homicide detectives who weren’t doing the job fast enough. The young, eager Gangster cops were duped by an egotistical police shrink, Dr. J. Paul de River, a doctor with no psychiatric training, who used the case to boost his career. De River focused on Leslie Dillon, a strange true-crime buff who reached out to him to offer his crime-fighting assistance. Precious time was wasted on a suspect who’d probably never met the Dahlia.

The cops were looking for a sick brute who, among other things, slit the Dahlia’s mouth from ear to ear, gouged the rose tattoo from her thigh and shoved it into her vagina, and sliced her in half with precision. Could he have been the med-school dropout Short briefly dated, who’d worked alongside medics in the war? How about the restaurant owner she temporarily lived with, who grew jealous of her other beaus and ejected her? Or, did she just have an unlucky encounter with a psychotic stranger?

Back in January 1947, a week into the investigation, with all potential leads having quickly gone dry, the head detective, Harry Hansen, spoke to reporters. “We’re right back where we started. We’ve got nothing.” All these years later, they’ve still got nothing, but we’ve got Mann’s outstanding chronicle of the sordid case.

Diane Kiesel is a former judge of the Supreme Court of New York. Her latest book, When Charlie Met Joan: The Tragedy of the Chaplin Trials and the Failings of American Law, was published in February by the University of Michigan Press.