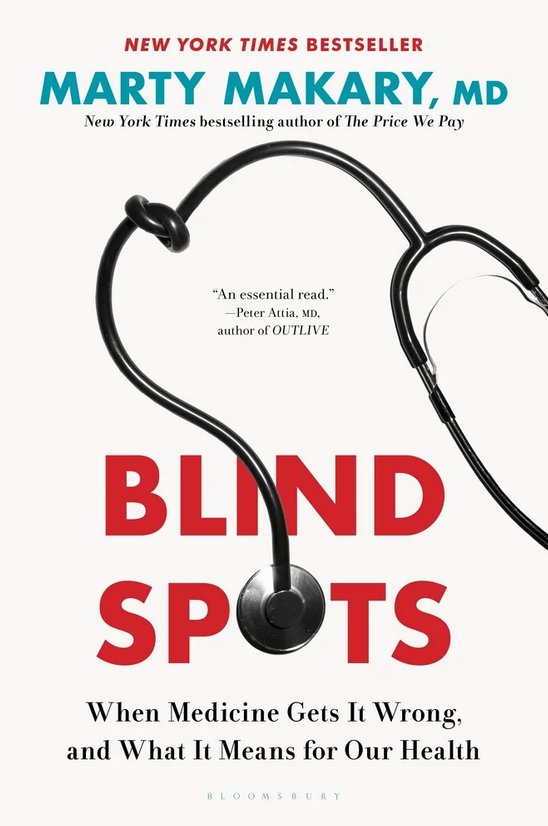

Blind Spots: When Medicine Gets It Wrong, and What It Means for Our Health

- By Marty Makary

- Bloomsbury Publishing

- 288 pp.

- Reviewed by Randy Cepuch

- October 4, 2024

How much is that dogma in the window?

In some ways, doctors are no different than the rest of us: They tend to believe what they’re told, and they struggle to keep up with change. Even as we’re relying on them to keep us healthy, they’re often relying on dogma — a word that appears hundreds of times in this book and is defined as “an idea or practice given incontrovertible authority because someone decreed it to be trust based on a gut feeling.”

Blind Spots: When Medicine Gets It Wrong, and What It Means for Our Health by Marty Makary (a surgeon and professor at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and leader of the Evidence-Based Medicine and Public Health Research Group) takes on more than a few costly and dangerous shibboleths. He dares to ask, “Could it be that many of our modern-day health crises were caused by (or hastened by) the hubris of the medical establishment?”

Raise your hand if you believe even one of these things: Infants should be kept away from peanuts. Hormone Replacement Therapy increases the odds of developing breast cancer. Antibiotics do no harm. Cholesterol levels are the primary factor when considering heart disease. Breakfast is the most important meal of the day. Ovarian cancer originates in the ovaries. Marijuana is harmless. Fevers are bad and should be reduced immediately. Early-detection tests for cancer are always godsends.

(Okay, you can put your hand down now. But it was up, wasn’t it?)

The aforementioned are all among the myths debunked in this fascinating and occasionally terrifying look at how modern medicine suffers from junk science and “groupthink.” How can that be? Aren’t all drugs and procedures subject to rigid and definitive tests before being put into practice?

Well, no. Makary observes that “over 10,000 medical journal articles were retracted in 2023, setting a new record.” Part of the problem is that the scientists authorizing research grants or editing medical journals tend to be seniors in the medical profession who’ve spent many years doing things just so — for reasons they can’t always explain and that sometimes don’t hold true.

It’s not that medical thinking doesn’t progress. We no longer see any of those “More doctors smoke Camels” ads that were common in the 1950s. It’s painfully slow, though — sometimes literally painful. As recently as the 1970s, Makary writes, “Pediatricians and obstetricians were taught that premature babies had nerves too underdeveloped to feel pain. Even major operations were done on preemies without anesthesia.” Until the 1990s, some especially unpromising preemies were simply put in closets to die quietly. (One who luckily dodged this fate went on to become a doctor quoted in this book, despite a treatment of pure oxygen shortly after birth that left him blind in one eye.)

While much of Blind Spots encourages skepticism, anti-vaxxers who insist that some of those who’ve taken the Hippocratic Oath are hypocrites regarding covid will find little support here. Instead, they’ll find the story of how, more than 200 years ago, a doctor demonstrated that exposure to cowpox led to immunity from smallpox — the dawning of vaccines — and how Thomas Jefferson created the National Vaccine Institute to begin the ultimately successful eradication of the disfiguring illness.

Misguided and unhelpful resistance to medical progress isn’t new, of course. In the 16th century, theologian Michael Servetus dared to suggest that the heart pumped blood through the body. Writes Makary:

“His theological beliefs got him in trouble. John Calvin had him arrested for heresy and he was burned at the stake. Publish or perish, they say. Sadly, for Servetus, it turned out to be both.”

That’s certainly an unlikely fate for Makary, a co-developer of now widely used surgical checklists (similar to flight checklists used by pilots) and the author of two previous New York Times bestsellers, The Price We Pay: What Broke American Health Care — and How to Fix It (2021) and Unaccountable: What Hospitals Won’t Tell You and How Transparency Can Revolutionize Health Care (2013).

But just as medications come with warning labels, so does this book. Before the table of contents, there’s a publisher’s note indicating that what follows is “not intended to provide medical advice to individual readers. To obtain medical advice, the reader should consult a medical professional who will dispense advice based upon each reader’s medical history and current medical condition.”

Sure, but Blind Spots will help you learn several critical and surprising things about what to ask and what to avoid, and it’ll encourage you to choose doctors whose treatments are based on evidence rather than hearsay.

Randy Cepuch is a frequent reviewer for the Independent and a member of its board of directors.