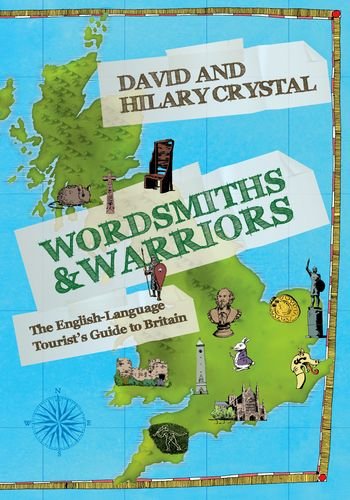

Bob Dylan: Things Have Changed

- By Ron Rosenbaum

- Melville House

- 304 pp.

- Reviewed by Charles Caramello

- December 4, 2025

A jagged exploration of the icon’s spiritual underpinnings.

A widely published and much-praised author and journalist, Ron Rosenbaum has written several books whose eclectic subjects range from Shakespeare to Hitler, from a defense of love to “travels with Dr. Death.” As a journalist, he worked as a staff writer for the Village Voice. He has contributed “influential long-form pieces” to the New Yorker, the New York Times Magazine, and other equally storied outlets of the zeitgeist. And, most pertinent, he interviewed Bob Dylan for Playboy in 1977.

Rosenbaum has listened closely to Dylan’s prodigious catalog of songs and albums since the 1960s, tracking their evolution and its correspondence to Dylan’s biography, and he clearly has mastered the now vast literature on the musician. Equally important, he enjoyed uncommon access to Dylan for a full week for his Playboy interview and, as he charges a fellow interviewer, is still “dining out” on the encounter. From his studies, interviews, and conversations with Dylan cognoscenti, he has fashioned in Bob Dylan: Things Have Changed an original if uneven piece of work.

Clear in his purpose, Rosenbaum proffers Bob Dylan as “a kind of companion to the songs whose secrets don’t always yield themselves up easily,” and as a book focused “on the lyrics rather than…crude biographical criticism.” Not a “formal biography” of Dylan, it offers, rather, “a biography of his impact on the consciousness of the culture,” or, more precisely, “a biographical essay about (and memoir of) that impact [and] an exploration of [its] source.” That key word, impact, recurs often, underscoring Rosenbaum’s contention, hyperbolic in letter but not spirit, that “Dylan has remade American speech, American thought, American attitude.”

Fleshing out that impact, Rosenbaum offers capable and perceptive analyses of three adjacent themes, or problems, in the Dylan canon: the self as “an infinite succession of discontinuous selves”; the self as tangled up in the warring rivalry between “sincerity” and “authenticity”; and, perhaps surprisingly, the self as a determined questor for “love.” Though he tricks out the first two with unnecessary references and allusions, he handles the third with a refreshing directness rooted in Dylan’s “love songs” as exemplified in the cuts on Blood on the Tracks, “one amazing hymn to regret.”

Rosenbaum identifies Dylan’s theodicy, however, as the principal source — and driving force — behind his impact and, together with Rosenbaum’s own theodicy, the force behind this book. Theodicy, the philosophical “attempt to reconcile the persistence [of evil] with a supposedly benevolent God,” defines the “argument with God” that Rosenbaum puts at the center of Dylan’s ethos. He situates it — for Dylan as individual and as representative of a generation — between “two Holocausts. Hitler’s and the nuclear one to come,” that he further identifies, in a shrewd turn, with two profound events in that generation’s formative years: “the Eichmann trial” in 1961 and the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis.

Rosenbaum’s thesis about Dylan’s theological bent shouldn’t surprise anyone who was paying attention, nearly six decades ago, to the album John Wesley Harding, or even, as the author correctly allows, to anyone paying attention to most of Dylan’s writing since then. In any case, he grounds his thesis in well-executed, persuasive readings of individual songs and albums. To that extent, Bob Dylan offers a rewarding and at moments compelling read, such as when Rosenbaum powerfully presents Dylan’s Nobel Prize lecture.

The book, unfortunately, also grates on the ear (at least on my ear), though this is evidently by design. Rosenbaum mimics throughout his text “that raspy, nasty voice,” as he nicely calls it, that’s easily identifiable as Dylan’s, particularly its sarcastic and supercilious version from Bringing It All Back Home through Blonde on Blonde, the albums bookending the height of Dylan’s “put-down” manner. While Rosenbaum, of course, can neither rival Dylan’s inimitable wit nor capture on the page his nasal and strident pitch, he does replicate the studied offensiveness of the man’s mid-1960s voice.

The book’s voice matches its content. Generally evenhanded, Rosenbaum can stoop to the mean-spirited — as in his gratuitous savaging of Allen Ginsberg’s presence on the Rolling Thunder tour — and rise to the hysterical, as in his ranting about the “Jesus freaks” who “hijacked [Dylan’s] soul for several years,” turning him into “a robotic preaching automaton.” Likely in excess of the facts, Rosenbaum’s passion here follows from his idée fixe that those “Jesus freaks,” as he repeatedly calls them, didn’t convert Dylan to Christianity so much as bamboozle him into betraying his deeply embedded if vexed Judaism, or, as the author puts it, “the Jesus betrayal (yes, I took it personally).”

Righteous anger, then, explains Rosenbaum’s obsessive rehashing of that “betrayal,” but it does not explain the book’s overall repetitiveness. Rosenbaum frequently restates points soon after introducing them, often in the same language. More vexing, he fixes on select Dylan phrases, notably, “It’s that thin, that wild mercury sound,” from the Playboy interview, and “on a whole other level,” a snippet from Dylan’s magnificent early jeremiad, “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll.” Significant in their original utterances and in Rosenbaum’s initial discussions of them, they become tedious when over-cited and suspect when employed as vague shorthand.

Bob Dylan, moreover, suffers from unironic preening. Keen to confirm both his scholarly bona fides and his journalistic street cred, Rosenbaum refers often to his Yale background and his other books, as well as to his many conversations with everyone from Vladimir Nabokov’s son to Johnny Cash’s daughter. In addition, if I might borrow one of his stylistic gambits, he’s very well read it’s well known, and to ensure that we know it, he conjures a seemingly endless parade of poets and novelists, theologians and scholars, philosophers and physicists from antiquity to the present.

But Rosenbaum’s mannered self-regard also serves to reveal the figure in the carpet hiding in plain sight: Not “a kind of biography” at all, Bob Dylan is, rather, a kind of autobiography — namely, the author’s Augustinian confession of his own theodicy, his own argument with God discovered independent of, but nurtured by, Dylan. Bob Dylan, put differently, belongs in the ranks of the film “I’m Not There” and other putative biographies of the man that comprise, instead, generically indeterminate, often imaginative homages to Dylan and others.

Seen from this point of view, Bob Dylan: Things Have Changed reads like an ambitious experiment in autobiographical New Journalism that went slightly awry. Nonetheless, the experiment has produced a solid contribution to the crowded Dylan library. Serious students will be obliged to read it, and casual fans are encouraged to. The book may not bowl over either group, but it will provide aficionados with a refresher, and novices with a foothold, on the theological side of Bob Dylan.

Charles Caramello is a professor emeritus of English at the University of Maryland and John H. Daniels Fellow at the National Sporting Library and Museum in Middleburg, VA.