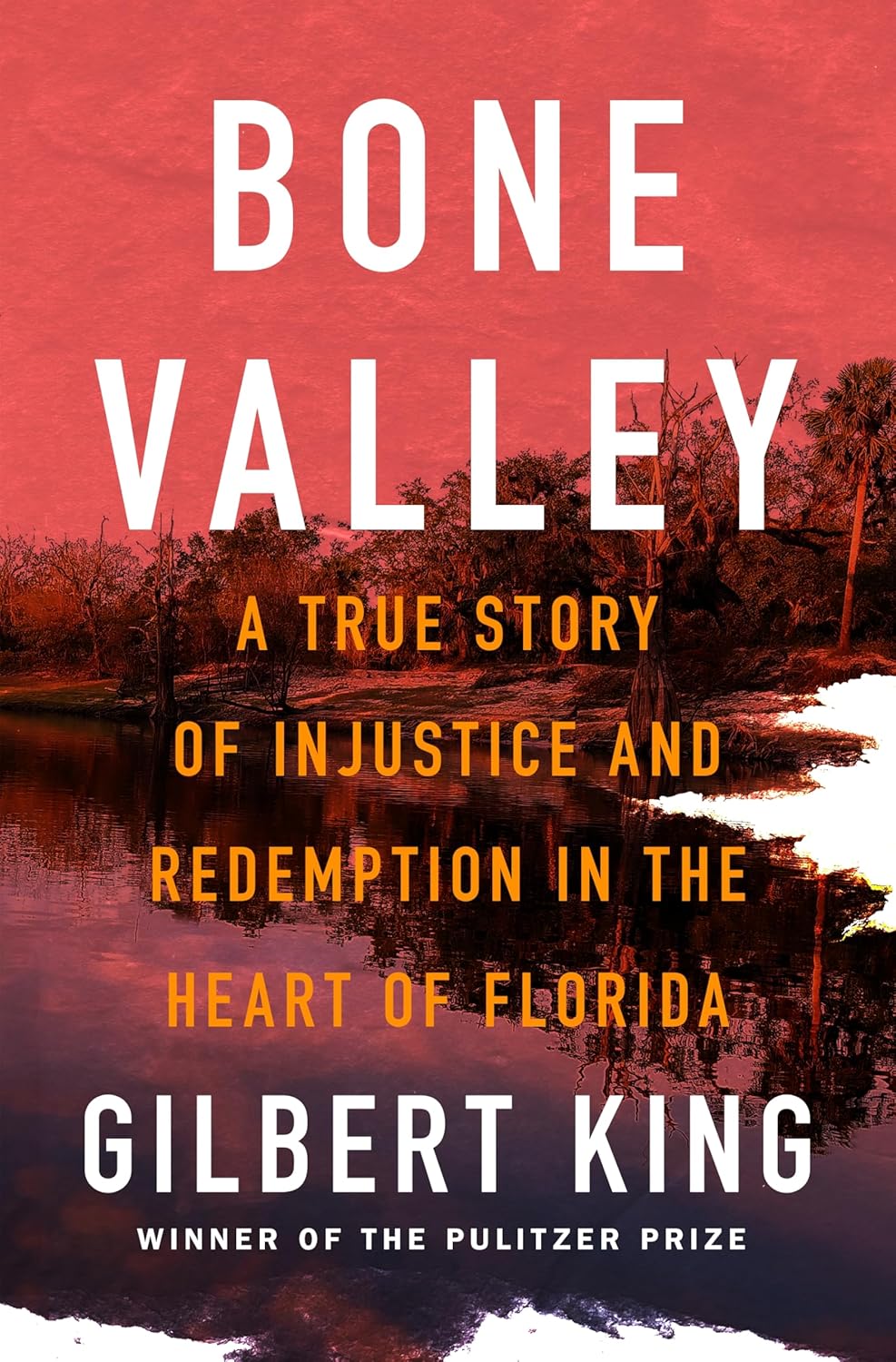

Bone Valley: A True Story of Injustice and Redemption in the Heart of Florida

- By Gilbert King

- Flatiron Books

- 384 pp.

- Reviewed by Mariko Hewer

- November 12, 2025

A gripping true-crime narrative recounted by a master storyteller.

Some tales of wrongdoing are so riveting, so flabbergasting, that the way they’re told scarcely seems to matter. Yet in Bone Valley, Pulitzer Prize-winning author Gilbert King lends additional tension and urgency to an already-unbelievable real-life horror story. (The book is adapted from the podcast of the same name created by King and his colleague Kelsey Decker.)

The first things we learn about musician Leo Schofield, convicted in 1989 of the brutal murder of his 18-year-old wife, Michelle, are not flattering. Somewhat of an outcast who could be “kind of hard to get along with,” according to a former bandmate, Schofield had a relationship with his wife that was often volatile and could escalate into physical abuse. But as King interleaves the tale of how he discovered the case with that of Schofield’s own past, it becomes increasingly clear that the story is more complex than it first appears.

It’s almost impossible to overstate the number of things that went sideways in Schofield’s murder case. A prosecutor who intentionally misled jurors, violated courtroom rules and ethics, and manipulated witnesses and suspects? Check. A defense attorney “whose grasp of the case was fragmented and inconsistent,” to the extent that he was later forced to testify that he should’ve had “a better understanding of character evidence”? Present and accounted for. Crucial evidence that eluded the defense’s scrutiny and may well have been actively suppressed by the state? Absolutely.

It is the resurrection of this crucial evidence, in fact, that helps jumpstart Schofield’s exoneration. When Schofield’s second wife, Crissie (whom he married while in prison), mentions his case to Judge Scott Cupp, her friend’s husband, in the early 2000s, he reluctantly agrees to review the transcript. Cupp is skeptical but is in for a surprise: “The State’s case didn’t make any sense,” he recalls. “It didn’t hold together logically or physically.”

When Crissie adds that there were “[t]wo sets of unidentified fingerprints [that] had been lifted from inside the car Michelle Schofield was driving the night she disappeared,” Cupp’s interest is further piqued. “Manual comparisons had ruled out both Leo and Michelle,” King reports, “but without the present-day state-wide database and without an alternative suspect for comparison, the prints had been filed away and forgotten.”

Yet after Detective Synda Williams, Cupp’s wife, runs the unknown prints through Florida’s Automated Fingerprint Identification System in 2004, she is shocked: They belong to Jeremy Scott, “a young man with an extensive criminal record of violent offenses in 1980s Polk County,” the very county where Michelle was killed in 1987.

Even with the recently uncovered evidence, it takes the Schofield team years to obtain a new hearing. Although the request is originally denied, an appellate court overturns this ruling, and Schofield is granted an evidentiary hearing to determine whether he deserves a new trial. In an episode of extraordinary mismanagement in the courthouse hallway, he comes within seconds of being chained to Scott, who is also there to testify in the matter.

“I know these people are not going to just walk the murderer of my wife right up in front of me in this tunnel,” Schofield recalls of his incredulous reaction. “If they march him up and put him alongside of me, that’s God’s will. I’m gonna end it right here in this hallway…Now you can go ahead and put me in prison. Now I belong there.”

Schofield’s haunting remarks are a powerful counterargument to anyone asserting prison is an effective deterrent to committing future crimes.

After his encounter with Scott, Schofield is engulfed by a rage that threatens to utterly consume him — rage stoked not by his wrongful conviction, but by his hatred for the man who murdered Michelle. Eventually, through prayer, he is able to see Scott, a disabled and deeply traumatized man, as just another victim of an unfair justice system.

Shortly after Schofield asks God to “let [Scott] know love for the first time in his life ever,” Scott begins speaking out about his involvement in Michelle’s murder. Although he’s often an unreliable witness (offering, for example, to take responsibility for all homicides committed in 1987 and 1988 as a way to commit suicide by death penalty), much of his testimony is compelling — and almost as riveting as the case’s astonishing conclusion.

Because Bone Valley was adapted from a podcast, there are moments that feel slightly out of focus or lack explanation, but they’re minor. King’s book will leave fans of true crime, social justice, and complex family narratives pondering its takeaways long after they finish reading.

Mariko Hewer is a freelance editor and writer as well as a nursery-school teacher. She is passionate about good books, good food, and good company.