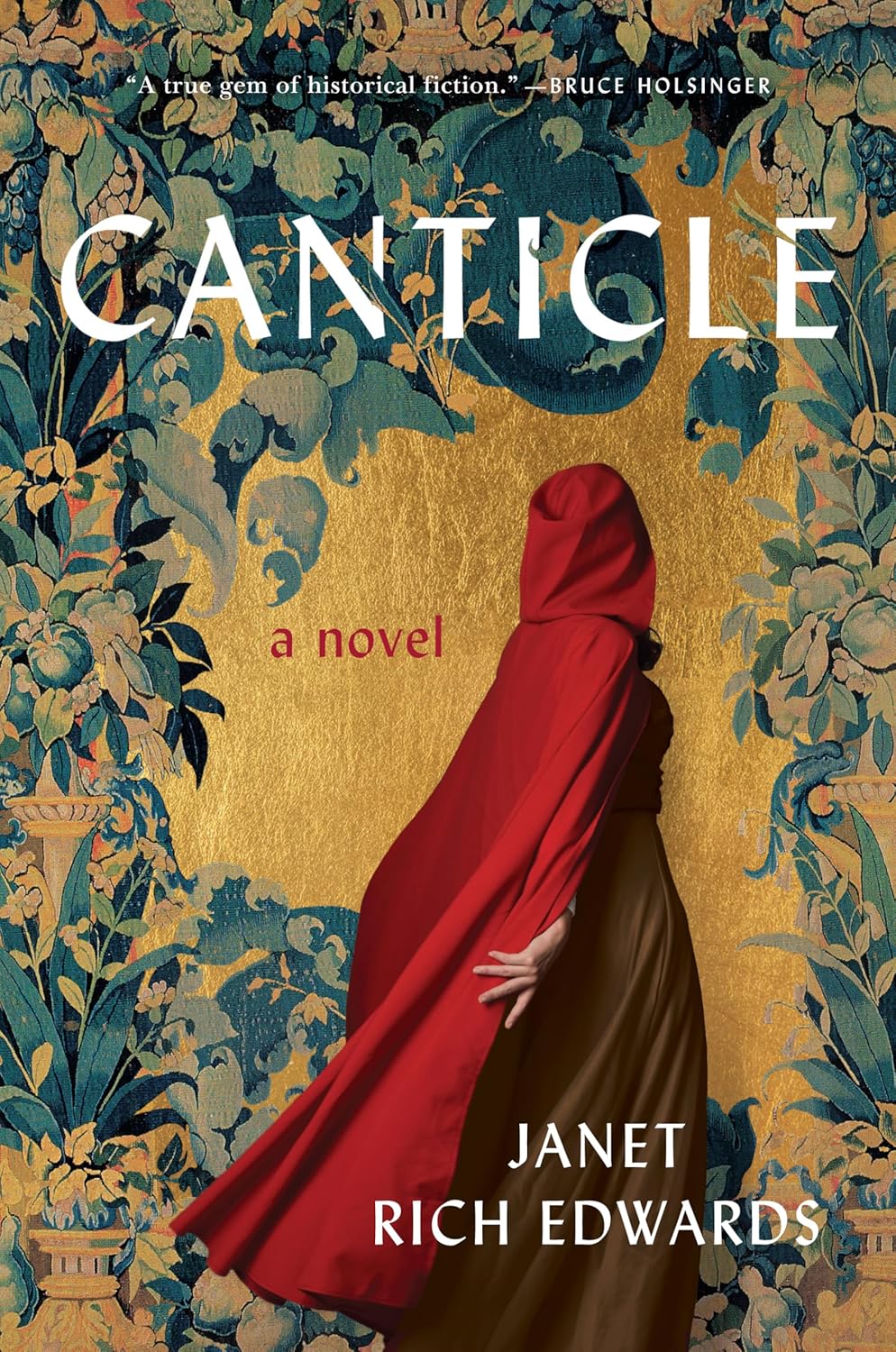

Canticle: A Novel

- By Janet Rich Edwards

- Spiegel & Grau

- 368 pp.

- Reviewed by Terri Lewis

- December 15, 2025

In 1299, a fervent young believer is sent to the stake.

Given that the United States is a secular nation, Janet Rich Edwards has taken on a daunting task with her debut novel. Canticle transports the reader into a world of faith at the end of the 13th century, when God and Church ruled. The story opens with a glimpse of Aleys on her way to immolation, surrounded by a crowd chanting, “Sint! Sint!” (saint). The remaining pages reveal how she came to be condemned.

Aleys’ family belongs to the Bruges underclass, preparing wool for local merchants. She’s an odd child, observing nature closely and always longing to get God’s attention. She also has a rich imagination. Here, her encounter with drying sheets in a yard:

“The wind shifts, a change in tempo, and the sheets on the lines begin to rise and fall in waves, a billowing ocean of snow, and Aleys imagines she could swim from one end of the courtyard to the other, where a gray stone church rises like a headland. The wind shifts again and the sheets snap like the wings of gulls rising from the sea. She can’t tear her gaze from them.”

It’s clear to the reader that a young girl capable of such feeling will not want to marry the older wool merchant who asks for her hand, no matter that his wealth would lift her family. Instead, Aleys runs away and, in a bold move, persuades Friar Lukas, a Franciscan who preaches in the city, to take her into his order. She can’t live among the friars, however, so he decides to place her with the beguines.

Today, the beguines — communities of devout women formed in the Netherlands and Belgium in the Middle Ages — are little known. Unattached to the Church and living in their own enclaves, they sought to emulate Christ, supported themselves, and spent time in religious contemplation. Often ministered to by Franciscans, they followed their own rules. Chastity was required within the beguinage, but they were free to leave and marry. The women’s independence and tendency toward mysticism made them a pain in the side of the religious hierarchy. In fact, in 1311, shortly after the novel’s end, the Catholic Church ordered the beguines’ dissolution.

In limning this unfamiliar ground, Edwards made a canny choice in selecting Aleys as her main character. Against Aleys’ fervor, the author has set Lukas, whose longing for God goes unanswered. The friar’s growing jealousy of the untutored girl seemingly preferred by God — she has visions, he does not — helps drive the plot. Another character, a cynical bishop, embodies the modern reader’s skepticism. Here, he contemplates plunder from a Crusade:

“The relics could bring in some cash, as long as the buyers believe they’re genuine…[He] views the sale of minor relics as a sort of holy lottery. Some buyers take home miracle-working bits and ends of martyrs. Others will be praying to knuckles of sheep farmers. Their coin is the same.”

Canticle revels in language, both in its prose and as part of the storyline. In early chapters, Aleys struggles to learn Latin, a subject forbidden to lay people and especially to women. She first awakens to love as she and a young boy translate the Song of Songs. Later, at the beguinage, the maistra (or leader) is translating Latin scripture into Dutch so the women can hear the holy text in their own language. This is also forbidden. As the bishop says:

“It took years of training to interpret the Bible…give them free access to the entire Bible in their mother tongue [and] people would start reading the scripture on their own, without the supervision of a priest.”

Edwards gives the bishop, Lukas, and Aleys markedly different voices. Aleys’ prayers beseeching God to come to her, and the resulting visions, unspool in prose poetry. A long section of the book in which she performs a miracle is astonishing. She prays the Ave Maria over a young boy. “The words are starched and stiff in her throat,” writes the author. “She feels like a fraud.” But she forges on until she “abandons herself to the graceful coiling words and ribbons of prayer curl into the air.” On and on Aleys prays, her faith palpable. When the boy eventually sits up, “the bed linen comes with him, stuck to his wounds so that he appears for a moment to be winged.”

Fortunately, the novel isn’t all mystery and longing; heart-stopping action is part of the mix. Once the miracle of the boy’s healing is performed, the story rushes forward. Crowds declare Aleys a saint, the bishop plots to use her to his advantage with the pope, and Friar Lukas’ jealousy reaches a dangerous peak.

In a surprise near the end, a fourth character is introduced: Marte, an innocent who takes us inside the power and danger of translation. Her version of the story of Lot, his wife, and the pillar of salt is telling and hilarious. It’s clear that she understands the world and how it’s set against women. (And the reader will understand how women who believe in God might come to doubt scripture upon hearing it in their own language.)

The narrative’s finale turns on Marte and her understanding of the Bible; the ending, although foretold, is devastating. While it is perhaps not for everyone, Canticle immerses the reader in a mysterious world made believable through the humanity of its characters and the glory of its prose.

Terri Lewis won the Miami University Press 2025 Novella Award. Her debut novel, Behold the Bird in Flight: A Novel of an Abducted Queen, the story of King John’s second wife, came out in June. She lives in Denver with her husband and two entertaining dogs.