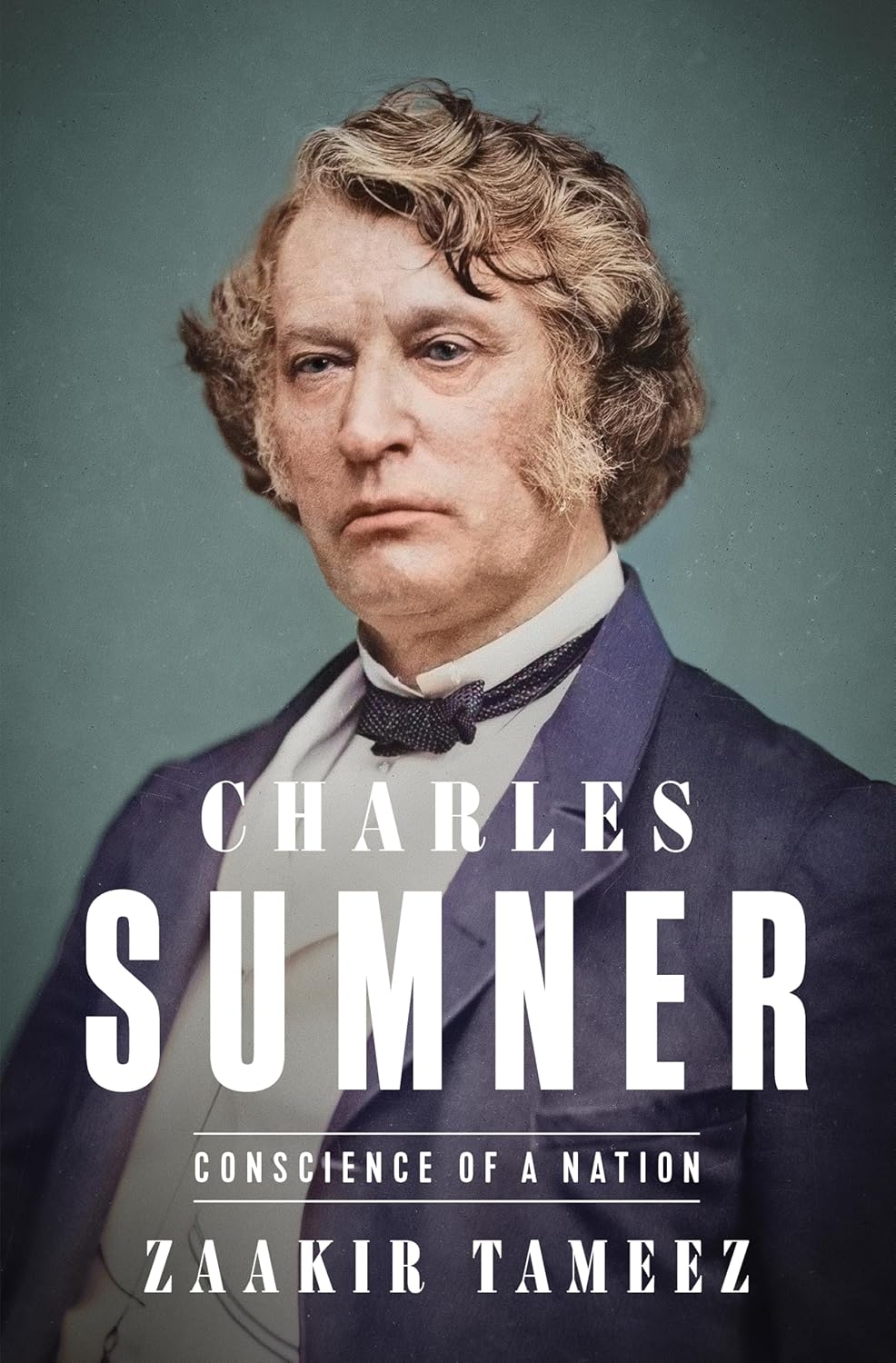

Charles Sumner: Conscience of a Nation

- By Zaakir Tameez

- Henry Holt and Co.

- 640 pp.

- Reviewed by Eugene L. Meyer

- August 18, 2025

The outspoken abolitionist is finally given his due.

Charles Sumner, the abolitionist senator from Massachusetts, is remembered, if at all, for his caning by South Carolina’s Rep. Preston Brooks in Congress in 1856. Sumner, badly bloodied but choosing not to fight back, recovered from the attack to become one of the most radical of the Radical Republicans who fought for Reconstruction and against the unreconstructed Confederates after the Civil War.

Otherwise largely forgotten, Sumner’s name is memorialized in the Charles Sumner School in Washington, DC, one of the first schools in the District for African Americans and now a museum, and, ironically, in the name of the all-white elementary school in Topeka, Kansas, that Black pastor Oliver Brown filed a lawsuit against so that his daughter could attend. That suit turned into the 1954 U.S. Supreme Court decision known as Brown v. Board of Education that outlawed school segregation across the land.

Charles Sumner: Conscience of a Nation isn’t the first Sumner biography, but it offers to show the man in full, more so than in earlier efforts that tended to emphasize his flaws rather than celebrate his accomplishments. This latest book about Sumner, by Zaakir Tameez, a young Yale Law School graduate, is no hagiography; it presents a complete picture of a man who could be ill-tempered, unyielding, and self-righteous. He was a lawmaker who may have been gay and who married only late in life, a union that lasted just three months. He was, he told others, “married to the constitution,” a fair description of his great and enduring love.

This is a bulky book with many nuggets awaiting the dedicated, patient reader. Sumner sued to integrate the Boston public schools, foreshadowing the Brown decision by a century. In the suit, he was the first to enunciate the concept of “equality under the law.” His challenge was rejected and, paradoxically, the decision was used in Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896 to bolster the “separate but equal” doctrine justifying segregation. Still, his arguments would underpin the Supreme Court’s Brown decision 58 years later.

Sumner also could be confounding. While abhorring slavery, he defended the U.S. Constitution that allowed it. A staunch Unionist, he nonetheless was censured by the Massachusetts House of Representatives for opposing the wearing of uniforms to celebrate the Union victory. And although a Republican, he was not strictly a party man. He insisted the Civil War was being fought to end slavery, while fellow Republican Abraham Lincoln — worried about losing the slave-owning border states — claimed it was all about preserving the Union. He lobbied Lincoln to emancipate the slaves before he was ready to do so. But Sumner revered Lincoln and, the author writes, was at the president’s bedside as he lay dying from an assassin’s bullet.

Some of Sumner’s postwar positions seem especially resonant today. He called for a national popular vote to elect the president, scrapping the Electoral College. He feuded with President Ulysses S. Grant’s “redemption” plan for the South, which essentially allowed the return of white supremacy rather than the Reconstruction that Sumner and others demanded. He also opposed Grant’s plan to annex the island of Santo Domingo in the Caribbean. President Donald Trumps’s designs on regaining control of the Panama Canal or claiming Greenland and Iceland for the United States don’t feel too far removed from this history.

These parallels to our moment seem almost buried in the avalanche of biographical details offered here, but certain themes do emerge. Growing up on the Black side of Beacon Hill infused young Sumner with an affection and affinity for African Americans. And that feeling was reciprocated. Upon his death in March 1874, as his casket lay in state inside the Capitol Rotunda, 10,000 people walked by, nearly half of them African American, Tameez writes.

Though educated at the elite Boston Latin School and Harvard University, Sumner did not come from wealth. His father was a lawyer (but not a financially successful one) and a bastard son, which carried a taint. Sumner was an awkward boy, bullied and bookish, who grew into a tendentious man who towered over others in both height and eloquence. In Washington, he detested what he regarded as the ill manners of his Senate colleagues and, while anti-slavery, was friendly with the more mannerly Southern senators. Sumner also suffered from heart disease, which would eventually prove fatal. Even as his health was declining, he sought to enact a comprehensive civil-rights bill to end segregation in public accommodations, public schools, and cemeteries nationwide.

“Much has been done,” he wrote, “but more remains to be done.” Indeed, the sweeping bill that he championed would not become law until nearly a hundred years later. And, given our own current events, his next words were prescient:

“The great work is not yet accomplished.”

It's worth noting that the author, born in Houston, is the son of Muslim immigrants from a former area of India, and he dedicates this book to two “beloved family members” who died in plane crashes: “We await our reunion with you in the ‘gardens beneath which the rivers flow.’ inshallah.” His acknowledgments are replete with names that are multicultural and multinational, such is the global reach of his sources and associates. Immigration was not Sumner’s cause, yet the fact that his newest biographer emerges from such a diverse background would no doubt have pleased him. It’s really a testament to the richness of the country that Sumner loved despite its manifest flaws.

Sumner’s life, Tameez writes, shows that “individuals like him, with enough courage and drive, can alter the trajectory of American racial history, even if they are not able to succeed fully during their lifetimes.” But this book is as much about now as then. Tameez recalls the 2011 earthquake that damaged the Washington Monument, an obelisk begun with slave labor and completed by free labor. The fissures the quake caused, he writes, may “represent the painful aspects of American life, fissures from the past that have never closed. They will take a long time to heal. Yet the wounds of the past can heal, will heal, if the human rights work of those who came before is honored and continued.”

He ends with a quote from Sumner:

“Liberty has been won. The battle for Equality is still pending.”

Tameez modestly concludes by drawing on “Islamic tradition,” where “classical scholars ended their books by saying Allahu ‘alam, an Arabic expression that acknowledges the limitations of human knowledge. Studying the past proved to me how little I will ever know. For every stone I turned during my research, I discovered stones that I couldn’t.” But the ones he did turn serve to illustrate a life well lived and a story well told.

Eugene L. Meyer, a member of the board of the Independent, is a journalist and author of, among other books, Five for Freedom: The African American Soldiers in John Brown’s Army and Hidden Maryland: In Search of America in Miniature. Meyer has been featured in the Biographers International Organization’s podcast series.