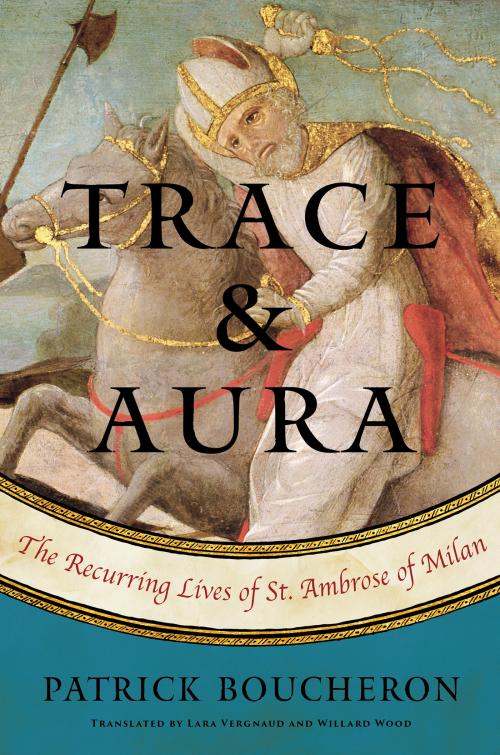

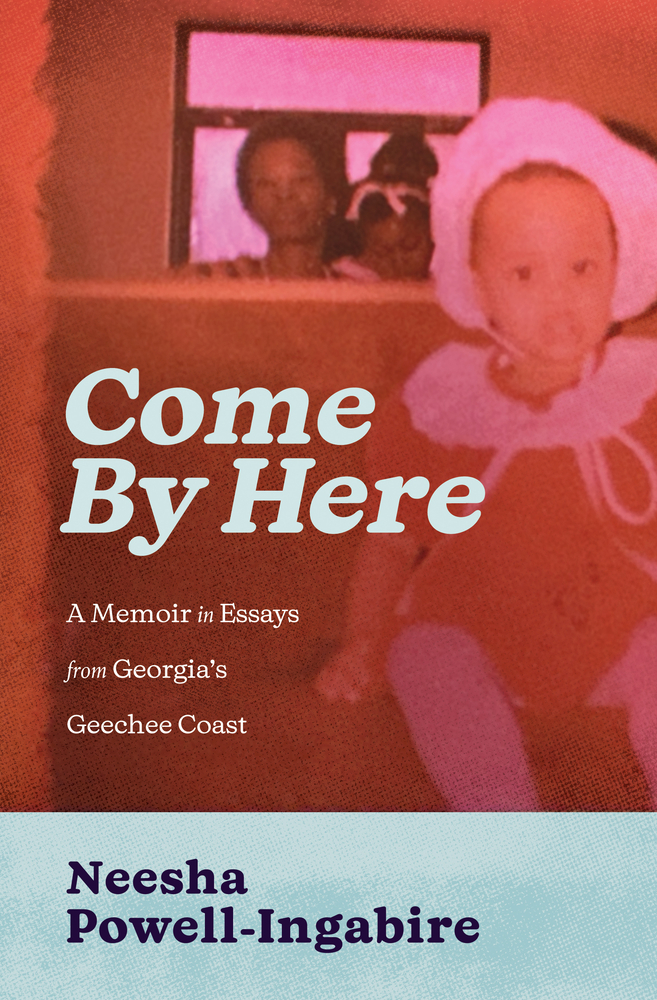

Come By Here: A Memoir in Essays from Georgia’s Geechee Coast

- By Neesha Powell-Ingabire

- Hub City Press

- 264 pp.

- Reviewed by Shelby Smoak

- October 8, 2024

A queer Black writer untangles her culture’s complex threads.

In her debut, Come By Here: A Memoir in Essays from Georgia’s Geechee Coast, Neesha Powell-Ingabire complicates an already intense genre by adding layers of removal to it. Her take on growing up Black in the South turns the screw when she adds being queer, disabled, and Geechee to the mix.

Her queerness and her ties to the Geechee community, initially dismissed when she was a child, become points of exploration in many of these essays, in which geography and culture are the true anchors that moor the author. She writes:

“I…seek to tell and preserve the story of my roots on Georgia’s coast and to bring people together to celebrate our culture.”

And so she does.

The opening piece sets up a recurring metaphor of Come By Here. The author’s quest for her grandmother’s grave — lost somewhere beyond a former plantation — echoes the unearthing of many buried things in her own life: her depression, the persistent racism of the Deep South, and the large industries that disenfranchise minorities and pollute the Geechee landscape.

The Gullah-Geechee community, composed of roughly 200,000 souls along the coastal waters from lower North Carolina to Georgia, has its own share of confusions and contradictions. Some separate the Gullah of South Carolina from the Geechee of Georgia. Others differentiate “Saltwater Geechees” from “Freshwater Geechees.” Powell-Ingabire, however, sees the culture as a single long extension from West Africa, one united by slavery and water.

Many have encountered a sliver of this culture through the sweetgrass baskets sold in Charleston markets and elsewhere. Recognizing that, the author’s essay “Baskets” explores the cultural significance of this weaving, noting that “each pattern is intentional and precise” and “has a story…[and]…a life of its own.”

Powell-Ingabire writes with unfiltered candor about her struggle with depression, a theme that becomes more raw in the memoir space. When she realizes she needs help and carries herself to Duke University Hospital, she’s immediately admitted after blankly telling a therapist, “I’m thinking about killing myself.” She doesn’t understand where her depression comes from but intuits that crying is its salve. “I don’t know how I would’ve gotten through that period without my tears,” she laments, launching into an essay on weeping that stands out as one of the book’s highlights.

Digging into the past, the author writes of public wailing as “an art as ancient as the Bible,” wherein the howling woman is “a powerful figure.” In contrast to this acceptance, as a child, her mother chastised her crying — “Don’t give me those crocodile tears” — so Powell-Ingabire stifled herself and felt “guilty” for crying when kids made fun of her crossed eyes and speech impediment. She then extends her musing to include our current world, in which “Black American tears are becoming cultural capital as TV executives, mostly white people, get rich off of them.”

The theme of racism pulses throughout Come By Here. In “The Confederate’s Son,” Powell-Ingabire comes to terms with her childhood best friend, Matt, whose father had a back room dedicated to the Confederacy. She didn’t mind the Rebel figurines and flags but now realizes her tolerance was a “veil” that “obscured what I didn’t want to accept.” Despite Matt’s continued reaching out to her in adulthood, the author shuns him, considering it “a systemic consequence of history.” This honesty is a hallmark of the work.

Still, some of the essays that engage directly with the topic of racism feel less successful; given their overreach, they often read like social-media posts. Her diatribe against the far Right and figures like Ron DeSantis and Elon Musk, for instance, lacks the local culture and rich personal characters that otherwise deepen the memoir’s voice into something unique. When the author hews closer to home — such as when she explores the dwindling of Geechee-owned property on St. Simons Island or decries the pollution poisoning local fishing waters — Come By Here strikes a pleasing balance between history and revelation.

So, who is Come By Here for? Honestly, it’s for readers like me, those steeped in Southern culture and literature, especially those whose families grew up near the Geechee. It ably demonstrates the expansiveness of that multifaceted, resilient culture. At its best, the memoir offers a window into a world that has long felt impenetrable to most of us. For providing that glimpse alone, Neesha Powell-Ingabire deserves our thanks.

Shelby Smoak is a writer and musician living along the North Carolina coast. His book, Bleeder: A Memoir (Michigan State University Press), received praise from sources as diverse as the Minneapolis Star Tribune, Library Journal, and Glamour, and has won several awards, including “Best of the Best” by the American Library Association. He was also featured on local TV and radio, including NPR. Awarded a Pen/American grant for writers living with HIV, Smoak holds a Ph.D. in literature and an M.A. in English. He works as the community relations and education manager in rare blood disorders for Sanofi.