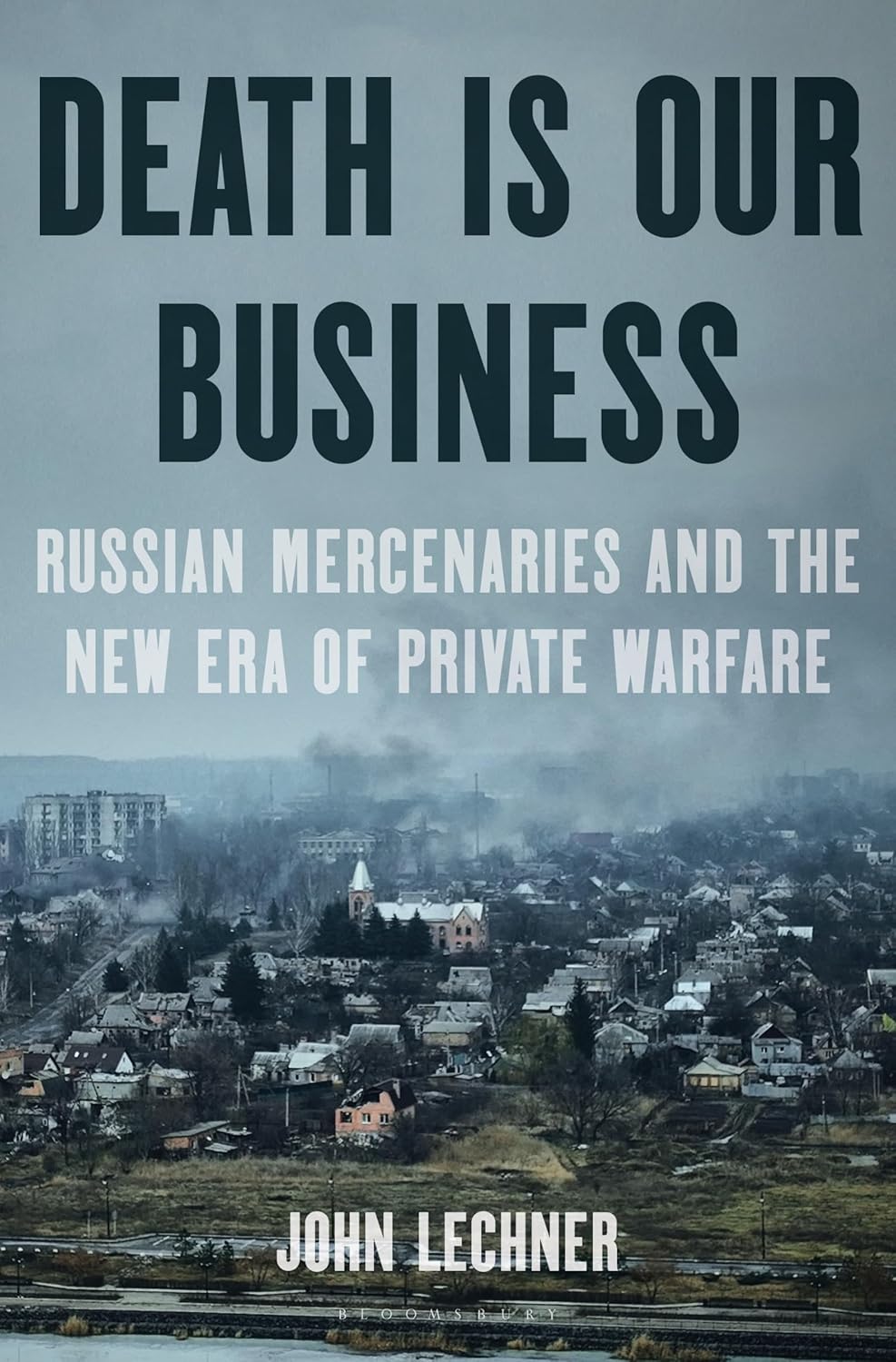

Death Is Our Business: Russian Mercenaries and the New Era of Private Warfare

- By John Lechner

- Bloomsbury Publishing

- 288 pp.

- Reviewed by Eric Dezenhall

- March 4, 2025

Wagner and the rise of the freelance tough guy.

When a plane carrying Yevgeny Prigozhin, boss of the private military contractor Wagner Group, went down in Russia in August 2023, conventional wisdom was that the country’s leader, Vladimir Putin, ordered his murder. Nevertheless, few of us knew what Wagner actually did — let alone how to pronounce its name — and how and why Prigozhin became powerful enough for Putin to allegedly want him dead. With John Lechner’s new book, Death Is Our Business, we get a full sense of why there may have been a target on Prigozhin’s back.

Wagner (pronounced VAHG-ner) was named by Dmitry Utkin, Prigozhin’s white-supremacist partner, after Richard Wagner, Adolf Hitler’s favorite composer. This gives one a sense of the kind of people we’re dealing with.

The simplest explanation for Wagner’s rise is that the company was willing to do what most governments and institutions weren’t — in very dangerous places, no less, including Ukraine, Africa, Libya, and Syria, to name a few. Moreover, Wagner recruited its combatants from Russian prisons — the inmates were pardoned by Putin — meaning that, unlike with the civilian population, if violent criminals were killed in combat, there would be minimal political blowback because, let’s be honest, who cares? Or so the logic went.

Wagner could also thrive because it operated with the protection of a Russian leader who ran a system where there was no transparency; therefore, the firm was unrestrained by oversight or the rules of war (such as they may or may not exist). In the event Russia was accused of meddling in places where it shouldn’t, the state could simply say, It wasn’t us. Who knows what those freelance loony-tunes are up to?

Lechner tells us Wagner’s origin story — the firm earning its stripes in Crimea, where its troops worked in tandem with Russian forces and took over the region with comparatively little bloodshed. This gave Wagner a ghostlike aura, which Prigozhin merchandised to his Russian clients and prospects around the world: Hire these guys, and they’ll make your problems disappear…

Wagner fought for the Assad regime in Syria, becoming involved with that country’s most lucrative businesses, including oil. They helped secure mines in the Central African Republic, where, in addition to providing military support, Wagner went into the mining business. They replicated this model in country after country, even participating in the online-trolling mischief to influence the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Along the way, Prigozhin made billions but didn’t necessarily cut his Russian clients in on all the booty.

Success in Ukraine allowed Wagner to market itself publicly. For reasons that the author acknowledges struck both Russians and Americans with “disbelief,” Prigozhin turned on the Kremlin and began openly feuding with Putin’s minister of defense. Flush with outrageous good fortune and few consequences for how he earned it, Prigozhin became a self-styled truth-teller bent on exposing the corruption of how Putin directed the war in Ukraine.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn he wasn’t.

As the tensions reached their zenith, a corporate jet carrying Prigozhin, Utkin, and eight others exploded and crashed north of Moscow. There is little dispute that sabotage was the cause and that its author was close to Putin.

Becoming famous for being a killer — such as celebrity “secret” agent James Bond — may be good for business on the front end, but in the long run, the notoriously violent have a way of making enemies. Somebody gets hurt along the way who has friends or relatives angry enough to come at you. In Prigozhin’s case, according to Lechner, one of those enemies was the Western news media. Indeed, after the media’s failure on the Trump/collusion narrative; the galloping impunity of global plutocrats; the ongoing Ukraine war prosecuted by Putin (who didn’t die from poor health like he was supposed to); and the murders of three investigative reporters in Africa looking into Prigozhin’s diamond-industry investments, the media found the Wagner boss to be an irresistible Bond villain.

To his credit, Lechner doesn’t fall into the trap of portraying Putin as an omniscient and all-controlling force, understanding that there were factions and unexplained developments in the interaction between the Kremlin and Wagner. “In other words,” he writes, “the Kremlin consumed the same ‘disinformation’ it produced.” This should be a sobering point for those who believe that everything we Americans don’t like is a result of immaculate orchestration.

Death Is Our Business has a Mad Max dystopian feel to it. One can see Hollywood adapting it into a film or limited series. A challenge, however, will be to wade through and separate the endless barrage of unfamiliar names, organizations, and acronyms that foreign-policy aficionados will devour but lay readers will struggle with. There’s a tension here between abundant journalistic rigor and storytelling clarity.

Perhaps more than anything in Lechner’s book, what will haunt the reader is what the Wagner saga portends for the future. Given how bellicose rhetoric still offends in some circles, the need to crack heads in the Age of the Potentate will remain. As the world embraces oligarchy and corporate chiefs get gunned down on city streets, private armies will become a more prevalent part of the landscape. And what about competition between businesses? Will we get to a point where toothpaste companies slug it out in a variation of My thugs can beat up your thugs?

Thugocracies fall in and out of fashion, but Death Is Our Business suggests that the market for private armies is so rich right now that, much like drug cartels, it will soon become lucrative enough for smoother, subtler iterations of Prigozhin and Utkin to ooze into the global economy. Hopefully, someone of Lechner’s skill and bravery will be there to watch it. Very closely.

Eric Dezenhall is the author of 12 books of fiction and nonfiction, including, most recently, Wiseguys and the White House: Gangsters, Presidents, and the Deals They Made.