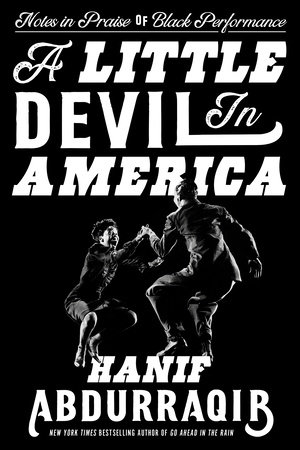

Djuna: The Extraordinary Life of Djuna Barnes

- By Jon Macy

- Street Noise Books

- 320 pp.

- Reviewed by Nick Havey

- December 27, 2024

Meet a queer, kinda-sorta literary starlet from the 1920s.

If I learned anything from the undergraduate class I took on early-20th-century American literature and culture — aptly titled “An American in Paris” — it’s that literati in the 1920s comprised a somewhat incestuous, incredibly connected group of people. From Ernest Hemingway to the Fitzgeralds, culture was community at that time (a far cry from the more diffuse cultural landscape today), and being a member usually meant fame and fortune.

Enter Djuna Barnes (1892-1982), the queer, crimson-haired heroine at the heart of Jon Macy’s gorgeous graphic biography, Djuna: The Extraordinary Life of Djuna Barnes. Born in an Upstate New York polygamist commune led by her father and grandmother, Djuna was one of the 20th century’s most iconic yet forgotten stunt reporters, writers, and all-around provocateurs. She loved art because her father, Wald Barnes, and grandmother Zadel Barnes loved it, but their pursuit of beauty came at the cost of nearly everything.

Zadel was a free-lover/reformer friend of all the famous gays, including Oscar Wilde. A pusher, a scammer, and a prime example of why Freud believed every trauma stems from one’s relationship with their mother (or, in this case, grandmother), Zadel was the architect both of Djuna’s razor wit and her misfortune. Her son Wald was a horny idiot obsessed with painting and with not providing for the two families he’d started. But after Zadel and Wald’s polygamist fantasy fails — the state informs Wald that he must choose one wife to keep — Djuna is forced to go to New York City to support the family by working as a writer.

Once she makes it to Manhattan, her life takes off. Soon, she builds the foundation that will get her to Paris and back. Along the way, she meets a charming German gallerist, forms a rivalry with poet Edna St. Vincent Millay, endears herself to T.S. Eliot, and sparks a friendship with Peggy Guggenheim that will keep her housed, clothed, and fed for much of her life.

In Paris, Djuna vows to “do a dangerous thing every day,” which is an excellent encapsulation of her ethos as a person. Her “genius” nets her a circle of friends that’s a veritable who’s who of American cultural elite, yet it’s her own middling success that is the focus here.

By the end of her days, Djuna is “the most famous unknown of the century,” writes Macy, but he’s done the work to render her life and legacy in vivid Technicolor (metaphorically, as the story itself is illustrated in black and white — although notable characters like Djuna have their hair colored).

Still, like Djuna the person, who couldn’t seem to focus on one genre in which to funnel her genius — she dabbled in journalism, poetry, prose, and a handful of other media — Djuna the book struggles in places due to its lack of linearity. It’s interesting to learn more about her backstory and the influences that informed her, but the narrative is a montage of halves. We see just enough of a character — say, Hemingway — to understand their impact on Djuna’s life but are pulled away to another vignette before we can formulate a question and get an answer.

But maybe that’s the point. Djuna’s life was expansive, and Macy has done a masterful job drawing brief attention (literally) to parts of it that I simply googled to learn more about, effectively rendering the unknown known. And to know Djuna Barnes is to be wowed.

Nick Havey is director of Institutional Research at the American Association of Colleges of Nursing, a thriller and mystery writer, and a lover of all fiction. His work has appeared in the Compulsive Reader, Lambda Literary, and a number of peer-reviewed journals.