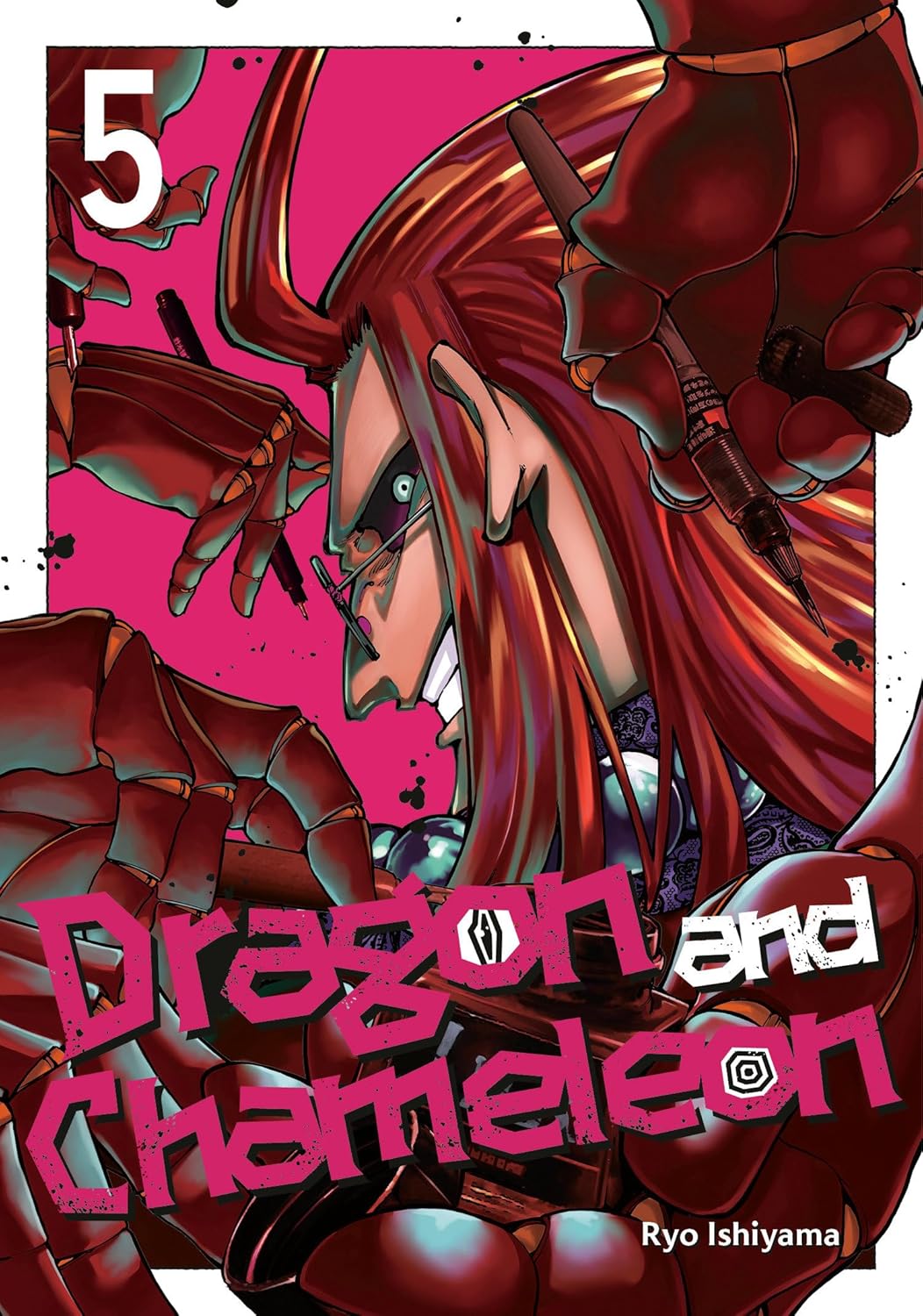

Dragon and Chameleon 5

- By Ryo Ishiyama

- Square Enix Manga

- 176 pp.

- Reviewed by William Schwartz

- December 25, 2025

Unacquainted with manga? Test the waters with this volume.

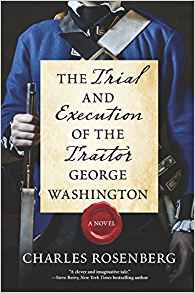

The back page of the fifth volume of Ryo Ishiyama’s Dragon and Chameleon frames the plot as a ferocious clash of artistic ideals. The description is an apt one for the manga series, which started out way back in the first volume when an inexplicable body swap placed Japan’s most popular manga artist, the titular Dragon, in the body of Shinobu Miyama, an unpleasant but highly talented assistant whose chameleon-like drawing ability allows him to mimic nearly any style.

In this fifth volume, the pseudo-Miyama attempts to launch a new manga series without the assistance of his original body’s brand, facing off with Fugaku, a rock-star rival whose grotesque stylings make him a close second place in the manga scene.

Dragon and Chameleon has distinguished itself by offering an exceptional look into the technical and aesthetic workings of Japanese manga production, with the pseudo-Miyama’s gaze providing an encouraging, optimistic presence to low-tier authors, unappreciated assistants, and even the true Miyama, who’s quite uninterested in returning to his real body.

Fugaku, however, gives off a very different vibe. He’s creepy and cruel. Pseudo-Miyama’s old mentor, Orochi, lures Fugaku into battling pseudo-Miyama in her manga magazine basically by promising herself as a sexual partner if Fugaku can beat the young upstart in reader polls.

This isn’t quite as bad as it sounds, as Orochi is a manipulative rock star in her own right — a crucial theme of this stage of the story. As pseudo-Miyama is more than just a little crazy, he’s happy to accept any manipulation in the name of producing better art. Dragon and Chameleon makes a point of noting how, just because a quality author is more likely than not to be a little unhinged, it doesn’t make them wrong.

Indeed, one of the most powerful scenes in this issue is Fugaku brutally tearing down one of pseudo-Miyama’s assistants, first with technical critiques, and then by closing with a vicious slam: Pointing out that no one has ever actually paid for her drawings, which may enjoy a strong online presence but nothing more.

Pseudo-Miyama’s brand of cheerful optimism provides a powerful contrast to Fugaku’s negativity. He continually chooses to interpret the realm of manga production as being one of collaborative artistic merit, never minding that the way the business is set up, artists are, by necessity, constantly forced to compete with each other. While Dragon and Chameleon is, in terms of its trade discussion, centered on the Japanese manga industry (and its unusually cutthroat nature), its lessons feel applicable to the publishing world in general.

If anything, Dragon and Chameleon might be a little too optimistic in its belief that the manga that rises to the top is necessarily the best. Still, manga as a genre is doing better worldwide than ever before, with adaptations of even relatively niche series like “Chainsaw Man” dominating the international box office.

Dragon and Chameleon, odd though its premise may seem, is one of the better places for readers unfamiliar with manga culture to discover what the appeal is. It’s not any individual work’s concept but rather its presentation and interpretation that makes manga at large such a big deal — and this volume in particular so informative about why that is.

William Schwartz is a freelance writer living in Southern Illinois. He has reviewed wide varieties of media, including South Korean dramas, upscale graphic novels, vintage videogame media, and much more.

.png)