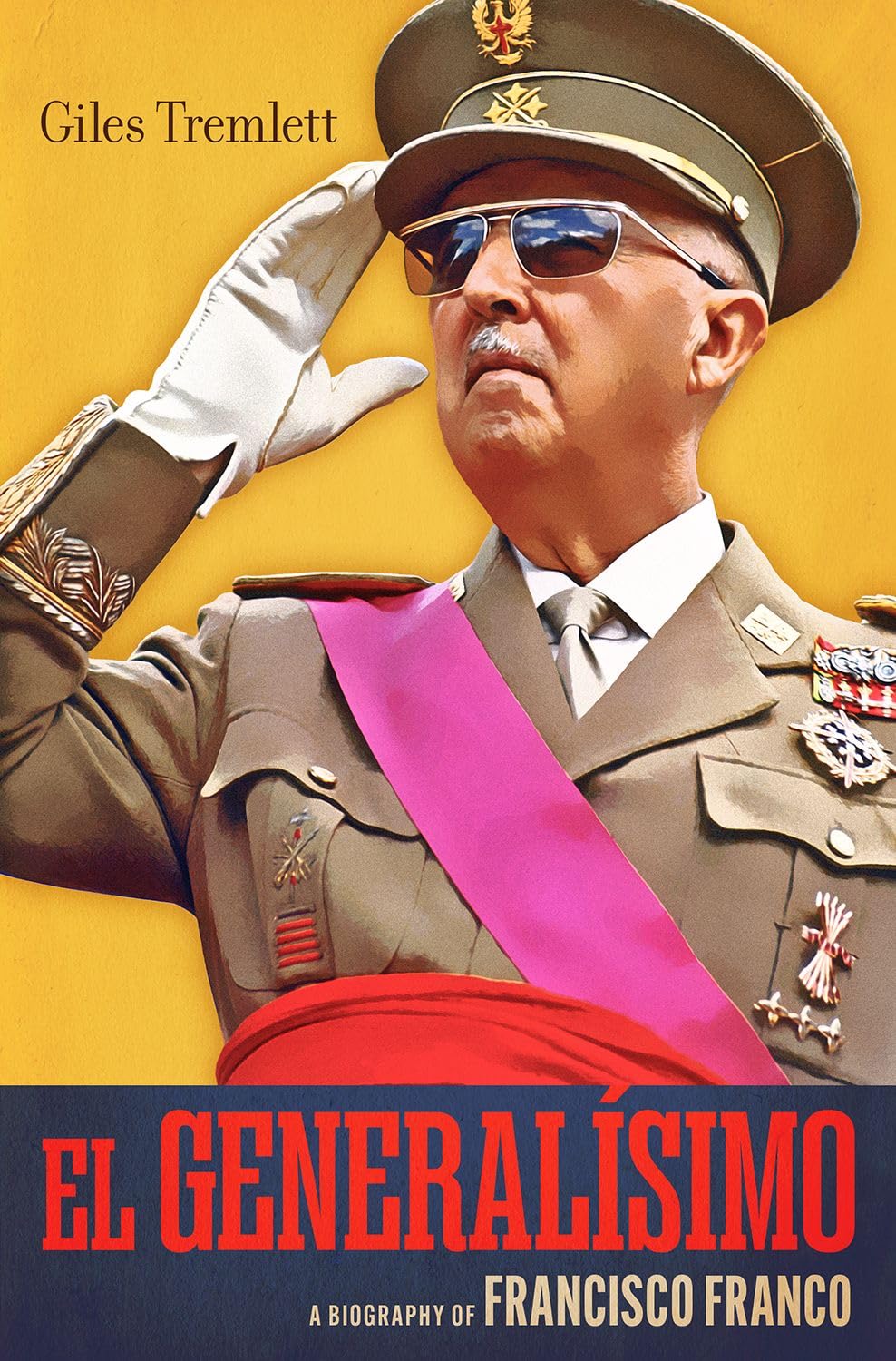

El Generalísimo: A Biography of Francisco Franco

- By Giles Tremlett

- Oxford University Press

- 528 pp.

- Reviewed by Andrew M. Mayer

- November 27, 2025

A masterful account of Spain’s former dictator.

In El Generalísimo, author Giles Tremlett offers a detailed biography of both the late, still controversial Francisco Franco, dictator of Spain from 1939-1975, and the legacy of Francoism he left behind. Tremlett, a former correspondent for the Guardian and the Economist, presents his subject as a product of his era, a soldier whose pragmatic allegiances shifted with the times. He was also a study in contrasts.

“In person, he could be mild-mannered, shy, courteous, sometimes humorous and often tediously dull,” writes the author. “As a leader, however, he was cold and ruthless.”

Franco rose through the ranks of the military in the 1920s and early 1930s, helping lead a successful charge against Muslim rebels in Spanish Morocco. Fueled by victories in Africa, he became one of the army’s youngest brigadier generals. A conservative Nationalist, Franco was never a supporter of his country’s left-leaning Republican leadership, nor of its liberal Second Republic. By the time civil war broke out in 1936, Franco — essentially the last man standing after several fellow rebels died in the military coup that sparked the conflict — controlled the Nationalists and was eventually named generalissimo.

Throughout his long, often bloody reign, Franco maintained his commitment to strong Roman Catholic rule, military dominance, and control of the press and public education. His perpetual foes included Freemasons, Jews, Socialists, and especially Communists. Whether he was a true fascist, though, remains the subject of debate.

During the Spanish Civil War, Franco managed to secure significant support for his Nationalists from Hitler’s Germany (by supplying it with grain in exchange for weaponry and air cover) and Mussolini’s Italy, a critical bulwark against the Soviet Union’s support of the Republicans. After his forces captured Madrid in 1939, ending the war, Franco signed secret pacts with Germany and Italy to continue aiding the Axis powers in World War II. While this cooperation was maintained through WWII, much of the secret diplomacy behind it wasn’t revealed until after Franco’s death in 1975.

Tremlett does an excellent job of chronicling the brutality of Franco’s Spain, pulling from records that only came to light in the last few decades. During the so-called “White Terror,” which started during the Spanish Civil War and lasted until after WWII, Franco took few prisoners. Instead, his henchmen massacred tens of thousands of opponents, be they leftists, homosexuals, or even rebellious clergy and their monarchist allies. (Franco was of two minds when it came to Spain’s monarchy. Although he’d been unhappy with the dissolution of Alfonso XIII’s reign and denied Alfonso’s designated heir, Infante Juan, the throne after WWII, he named Juan’s son his designated successor in 1969. King Juan Carlos I assumed power upon Franco’s death and ruled until 2014.)

Tremlett augments his interpretation of the Franco era with detailed analyses from Paul Preston, Hugh Thomas, and other prominent historians, thereby ably painting a picture of Spain before, during, and after the dictator. Among other things, Tremlett explores Spain’s questionable “non-belligerent” status during WWII, which Franco pragmatically adopted to avoid bombing attacks, while nonetheless quietly siding with the Nazis (which is part of the reason Spain wasn’t allowed to join NATO until 1982).

At every turn, the strongman dealt harshly with terrorists — particularly the Basque separatist group ETA — and recalcitrant everyday subjects alike. Writes Tremlett:

“The dictator imposed himself so thoroughly that Francoism could remain almost invisible to foreign visitors unless they themselves broke rules of public decorum (as bikini-clad women in the 1960s did) or chanced upon police exercising their unrestricted and unaccountable power.”

But if Franco was vicious, he was also canny. To maintain power for 36 years — a reign three times as long as Hitler’s and twice as long as Mussolini’s — amid a fluctuating economy and social turmoil, the man relied on both carrots and sticks, even if the former were largely illusory. “Freedom is never absolute, nor is repression,” explains the author. “One of Franco’s tricks was to hold out the idea that some restrictions might be softened (but not lifted entirely) at any time.”

In the final chapter, Tremlett makes clear how difficult it remains to assess Spaniards’ true feelings about their erstwhile dictator. Some post-1950 referenda showed that 86 percent of Spain’s citizens supported Franco, whereas, by 1994, only 16 percent of the public said they’d ever approved of the people’s “unelected king.” Yet, in 2025, on the 50th anniversary of his death, Franco continues to garner a degree of popular support.

Tremlett, at the outset of El Generalísimo, states that his book “seeks to understand not just Franco the man, but also to explain Francoism as a society-shaping phenomenon that reflected the dictator’s own character and interests above the influence of the factional ebb and flow around him.” By drawing from decades-old resources, recent archives, and the expertise of fellow historians, he has succeeded.

Andrew M. Mayer is professor emeritus of humanities and history at the College of Staten Island/CUNY.