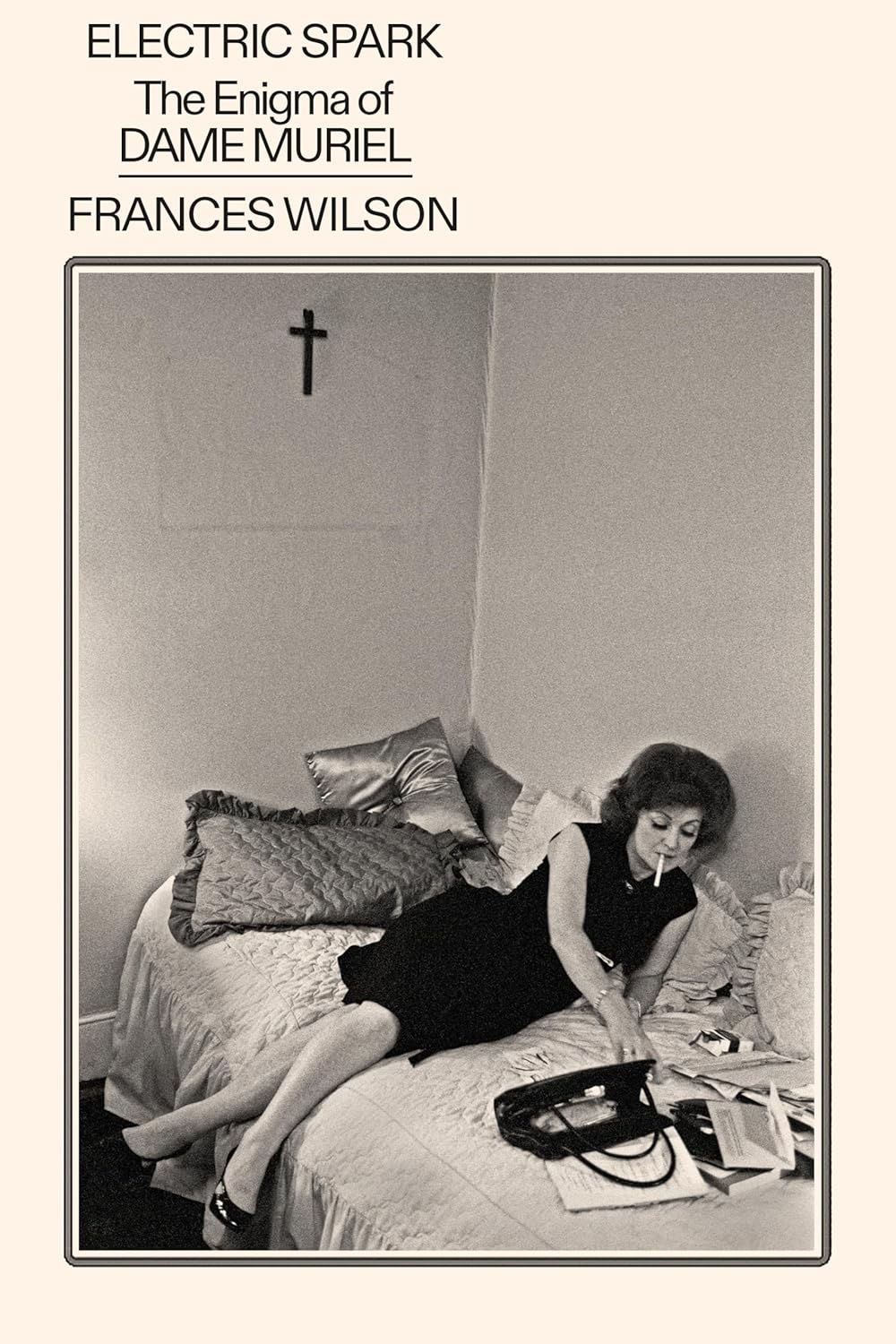

Electric Spark: The Enigma of Dame Muriel

- By Frances Wilson

- Farrar, Straus and Giroux

- 432 pp.

- Reviewed by Ellen Prentiss Campbell

- November 5, 2025

A formidable figure requires — and finds here — a formidable biographer.

In Electric Spark, award-winning biographer Frances Wilson takes on a complicated subject. Dame Muriel Spark, the prolific author who died in 2006 at age 88, may be best known for The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, one of her more than 20 novels, yet she also wrote short stories, poetry, radio plays, and an autobiography, Curriculum Vitae. Years before her death, Spark selected Martin Stannard as her biographer, initially giving him free range of her personal archives. Later, reading his drafts and dissatisfied by his work in progress, she broke off the collaboration. (Nevertheless, he published his book shortly after her death.)

Wilson demonstrates that infatuation, dissatisfaction, and cut-offs were typical of Spark’s relationships. Boundaries blurred between professional and personal, actual and imagined (or presumed) relationships. Given Spark’s fractious and sometimes litigious nature, it’s advantageous that Wilson researched, wrote, and published Electric Spark after the author’s passing. Spark claimed to desire a “literary biographer,” and she has one in Wilson. However, as is apparent in Electric Spark, she wanted accolades rather than critical evaluation of either her life or her work.

Spark “never threw anything away on paper,” amassing a hoarder’s trove of notes, drafts, and correspondence. Wilson mines the trove, both a treasure and a potential trap for the biographer. Her analysis of Spark’s work and chronicle of her life includes extended quotations from Spark’s letters. The primary emphasis of this biography is Spark’s literary development and oeuvre, but Wilson provides a concurrent exploration of Spark’s relationships and her mercurial emotional, mental, and spiritual states.

Spark’s voice as letter-writer is brittle, funny, and deliberately shocking. An annotated collection of her voluminous correspondence would be good reading; here, the degree of detail is sometimes repetitious. However, Wilson may choose overabundance to provide primary-source testimony and supporting evidence. Spark was, the reader learns, a most unreliable narrator of her own life.

The author comes alive in these pages as self-absorbed, self-aggrandizing, self-mythologizing, and hypersensitive to slight. Like Miss Brodie, Spark is a fascinating, unsympathetic character whose wounding arrogance covers vulnerability. Her fraught and disappointing relationships often end with perceived betrayal. Family bonds are only distant background. Episodes of mental distress approaching psychosis seem exacerbated rather than helped by the treatment of the day. Given Spark’s many difficulties, her prolific literary output is even more remarkable.

Wilson provides a chronological introductory account of Spark’s early years: Edinburgh childhood, brief marriage, divorce, and the decision to leave her son with her parents and move to London. She intended to become financially secure and provide a home for her child; this never occurred, and estrangement ultimately ensued.

Wilson divides the subsequent narrative into thematic sections exploring Spark’s intense, life-long interest (to the point of imaginative merger) with four historical figures all named Mary, as well as her real and imagined experiences. Rather than strict chronology, the narrative unfolds with some temporal shuffle back and forth, which can be confusing.

These shifts of emphasis between critical analysis and biography also occasion some narrative tension, which may be intentionally reflective of the protean Spark. Her life and work intertwined without balance or harmony — or, seemingly, much happiness. She fictionalized herself not just through her characters but by becoming her own created character. She transformed herself over the years from a Scottish schoolgirl and ambivalent “Gentile Jew” to a Catholic woman living in a Roman palazzo.

The book’s afterword — which addresses the biographer’s general dilemmas in writing a life, and Wilson’s specific ones in writing Spark’s — furthers the reader’s understanding of the inherent challenges of the genre. By no means a cursory coda, it gets to the nub of readers’ questions regarding biography and this biography. It might stand alone as an essay.

Spark, terminally ill, began a new novel in 2006. “She had written only five pages when she died,” Wilson says, “which is all she needed to make her point because a Muriel Spark novel is contained in its title.” Likewise, Frances Wilson’s own premise, hurdles, and conclusions are found in her title: Electric Spark: The Enigma of Dame Muriel. She is an apt student of her subject, and Spark indeed may have found her desired literary biographer here. Just possibly, Wilson’s reading of the work and the woman behind it might even have elicited partial approval from the irascible author.

Ellen Prentiss Campbell’s collection of love stories is Known By Heart. Her collection Contents Under Pressure was nominated for the National Book Award; her novel The Bowl with Gold Seams won the Indy Excellence Award for Historical Fiction. Frieda’s Song was a finalist for the Next Generation Indie Book Award, Historical Fiction. Blogging as “Girl Writing” in the Independent bi-monthly, she lives in Washington, DC. For many years, Ellen practiced psychotherapy. Her new novel, The Vanishing Point, will appear in spring 2026.