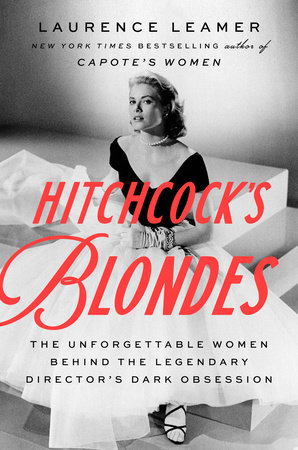

Four Points of the Compass: The Unexpected History of Direction

- By Jerry Brotton

- Atlantic Monthly Press

- 224 pp.

- Reviewed by Anne Cassidy

- November 11, 2024

Did you ever wonder why north is up and south is down?

Most of us have seen the famed Blue Marble photograph of earth, the first time an image of our planet was captured from space. We know that the shot inspired environmental activism and a sense of shared humanity. What we may not know is that the image we see isn’t the one snapped by the crew of Apollo 17.

The original photo was oriented with the southern hemisphere above the northern. A weightless astronaut couldn’t tell what was up or down, so the raw image shows the South Pole at the top of the frame, with Africa and the Arabian Peninsula below. Scientists at NASA thought the reversal might confuse viewers, so they flipped the image before releasing it.

“The world was literally turned upside down: but which way up is true?” asks Jerry Brotton in his fascinating new book, Four Points of the Compass: The Unexpected History of Direction. North doesn’t have to be on top, he says, but there’s quite a story behind why it is.

North, south, east, and west don’t just help us navigate the world; they tell us who and where we are. The directions preceded the points of the compass; they gave humans the ability to locate themselves in space, to describe where the sun rises and where it sets. Some Indigenous peoples have such a keen sense of cardinal direction that they say, “Please move to the west” instead of “Please move to the left.”

Why four directions and not some other amount? Consider the human body. Our most basic orientations are front and back, left and right. The number four is also linked with the cross and the square, with totality and completeness, Brotton explains.

The earliest surviving depiction of the four cardinal directions is found in the Gasur Map, a clay tablet from the third millennium BCE discovered in modern-day Iraq. It refers not to astronomical observations but meteorological ones: the four winds. It wasn’t until Charlemagne’s rule in the early 9th century that wind names dropped out of the descriptors and directions began being based solely on the sun’s movement. Charlemagne is also responsible for naming the directions nord, est, sund, and oëst.

Magnetic compasses didn’t appear in the Mediterranean until the 12th century CE, but the Chinese were using them as far back as the 2nd century BCE. Chinese compasses pointed south, by the way. So why did the north win out? A convergence of classical geometry — Greeks used the Pole Star to find their way — and maritime navigation. As Europeans colonized Africa, Asia, and the Americas, maps with other orientations became obsolete.

Speaking of orientations, Brotton is at his best when he analyzes how directional terms have come to define us. For example, to “orient” ourselves comes from the Latin oriens, which means “east” or “rising.” But using the word “Orient” to describe Asian countries allowed Europeans to define a large swath of the world as “the other” and to dominate it.

Brotton gives each direction its own chapter, beginning with the east. The rising sun brings light, warmth, and comfort — no surprise it’s linked with new life. Polytheistic religions worshipped the sun, and east remains an important direction in both Judaism and Christianity.

Although the west is often associated with death because of its tie to the setting sun, it’s also connected with rebirth and new life. The west is a place of possibility, a realm of the imagination, home of Atlantis and other fantastical places. While, in the U.S., the west is linked with the frontier and Manifest Destiny, Henry David Thoreau equated it with wildness, which he saw as the “preservation of the world.”

North is “one of the most powerful yet contradictory markers of personal identity,” writes Brotton, who hails from the north of England. While, in his country, the north has been seen as lagging behind economically, in Italy, directional identities are reversed, reminding us of their relativity and how often these markers derive meaning from their opposites.

Which brings us to the south, a direction that may be on our minds these days as the northern hemisphere tilts into winter. Traditionally associated with warmth and beauty, this is a direction on the move, as countries of the Global South come into their own.

Brotton, also the author of A History of the World in 12 Maps, ends his new book with a plea to keep maps, compasses, and the cardinal directions in our lives. If the human brain’s hippocampus can grow from intensive map study — and research on London cabdrivers proves that it can — what’s to stop it from shrinking with disuse?

It’s an important question to ask as more and more of us outsource wayfinding to our electronic devices. In the decades since the Blue Marble, we’ve become enamored of another blue dot, the blinking digital one our phones use to give directions. After reading Four Points of the Compass, it’s hard to ignore what we’ve lost in the process.

Anne Cassidy has been published in many national magazines and newspapers, including the Washington Post, the New York Times, and the Christian Science Monitor. She blogs daily at “A Walker in the Suburbs.”