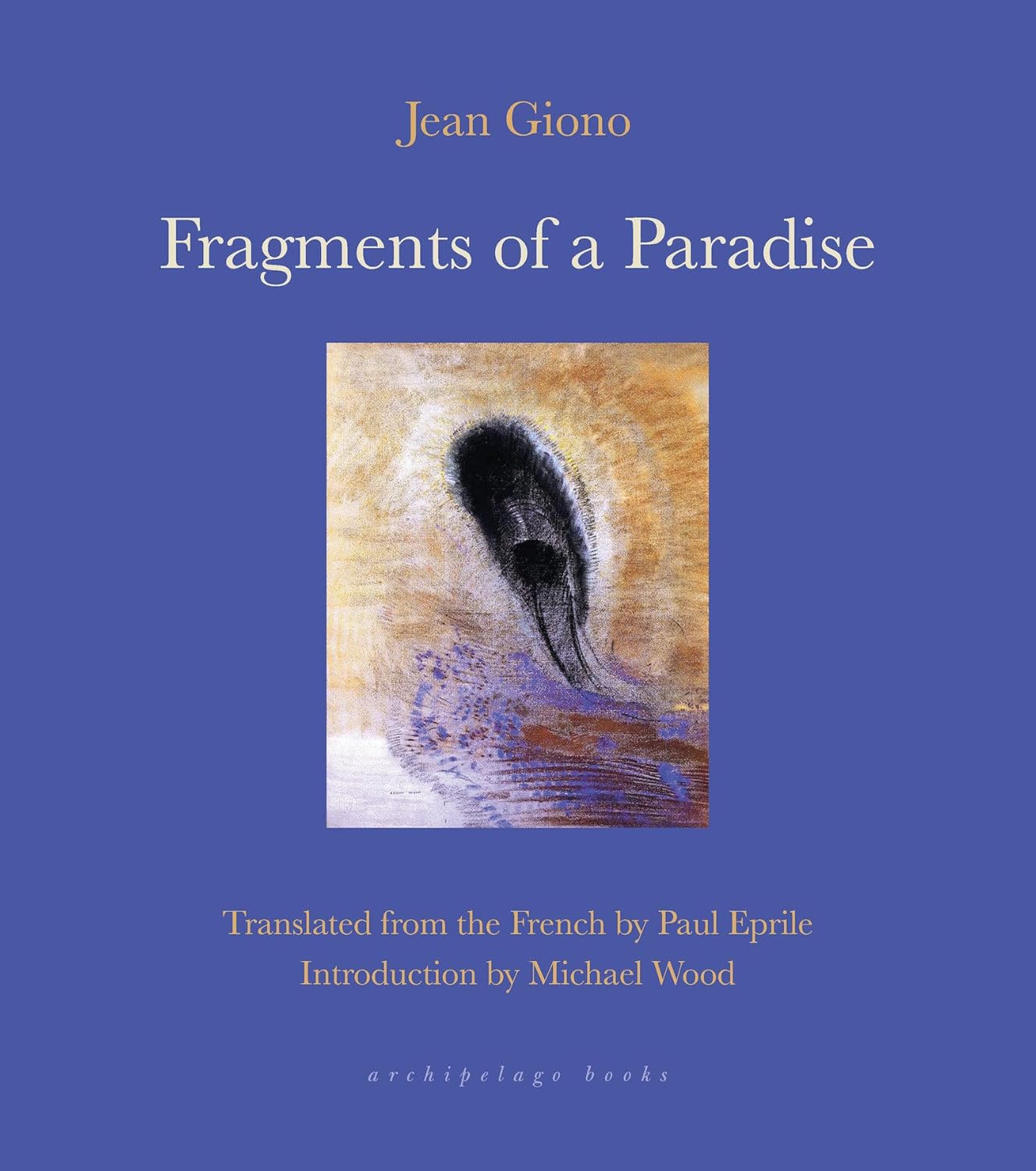

Fragments of a Paradise

- By Jean Giono; translated by Paul Eprile

- Archipelago

- 215 pp.

- Reviewed by Mike Maggio

- November 6, 2024

A journey of discovery leads to a world devoid of people.

Character, as we all know, is one of the most important elements of fiction. Out of character grows conflict, and out of conflict, story emerges. Without these two elements, story is unformed and leaves the reader uninterested and unsatisfied.

Conflict typically involves individuals — people whose lives become intertwined in some way that leads to struggle. However, conflict can also exist between individuals and nature (The Old Man and the Sea, Moby-Dick) or between individuals and themselves (The Great Gatsby, Beloved). But what if nature is the true protagonist and humanity serves only as a backdrop? What if conflict exists secondarily or not at all? How will story unfold and readers respond? These questions lie at the heart of Fragments of a Paradise, a brilliant novel by Jean Giono (1895-1970).

Giono’s tale is ostensibly about a group of 20th-century sailors who embark on a journey of discovery in a 19th-century ship — an anachronism powered solely by the wind. The narrative is set in a post-World War I world, but the captain chooses this antiquated craft because he “doesn’t want to be dependent on coal yards, which would force [him] to set foot in civilized countries.”

In this way, Giono sets up his initial premise — nature as the overriding force to which humanity submits — and creates a construct in which humanity becomes the antagonist.

Throughout Fragments of a Paradise, Giono plays with perspective, switching points of view unexpectedly. The story opens in third person, with an omniscient narrator and no specificity of character, and it continues that way until the end of the second chapter. Even then, we’re given only a name — Hourdeau — and no details about who he is. He just appears out of nowhere as if his presence is accidental or he doesn’t matter in the larger scheme of things.

As the novel continues, the narration switches from third person to various first-person perspectives, and we begin to meet the others aboard the ship — characters who, in literary terms, can only be described as flat. Like Hourdeau, they are simply there, and while we learn some specifics about each, there’s no real character development (minus some very explicit details) and, more importantly, no interpersonal conflict.

Contrast this with the depiction of nature: the waves are “glassy rollers”; the wind “beats” or “swells” or “pummels”; and the sea rises “into a dome” or forms “a sort of vault.” The sky, the horizon, and the sea life (including supposed sea monsters) the sailors encounter are rendered as mysterious manifestations of playfulness. The natural world provides the elements of conflict, yet no real conflict exists.

And then there’s the island they come upon — a place lacking signs of human life, except for a shack that contains enigmatic evidence of recent inhabitance:

“Hanging on the door was a huge, woven basket made from strands of dried seaweed. Out of this gourd-shaped receptacle, Guinard pulled a skirt and a blouse. At the bottom of the basket, there was also one of those broad, long-handled knives with a blade five centimeters wide and twelve long, slightly curved and finely ground, the kind whalers use. There was much debate about the women’s clothes; they didn’t seem very old. What’s more, they seemed to have been worn recently.”

But no one is found.

Not accidentally, the sailors find two books in the abandoned shack: Don Quixote in Spanish and Paradise Lost in English. These clues for the reader suggest a world that’s been forfeited due to mankind’s follies. In this world, it is nature that dominates. It lives and breathes; it is tactile and emits odors that alternately delight and disgust. It has the power to move ships forward or to leave them stranded. And ultimately, it has the power to obscure humanity altogether.

Despite its lack of a plot, Fragments of a Paradise is anything but boring. The prose is stunning and carefully wrought, and the translation by Paul Eprile is superb. Giono was a longtime pacifist, a stance he took after serving in the First World War. Perhaps he meant Fragments of a Paradise to be his paean to peace, one in which the world survives even if the humans wreaking havoc on it do not.

Mike Maggio’s newest novel, Woman in the Abbey, a gothic tale of faith and temptation, will be released by Vine Leaves Press in February 2025.