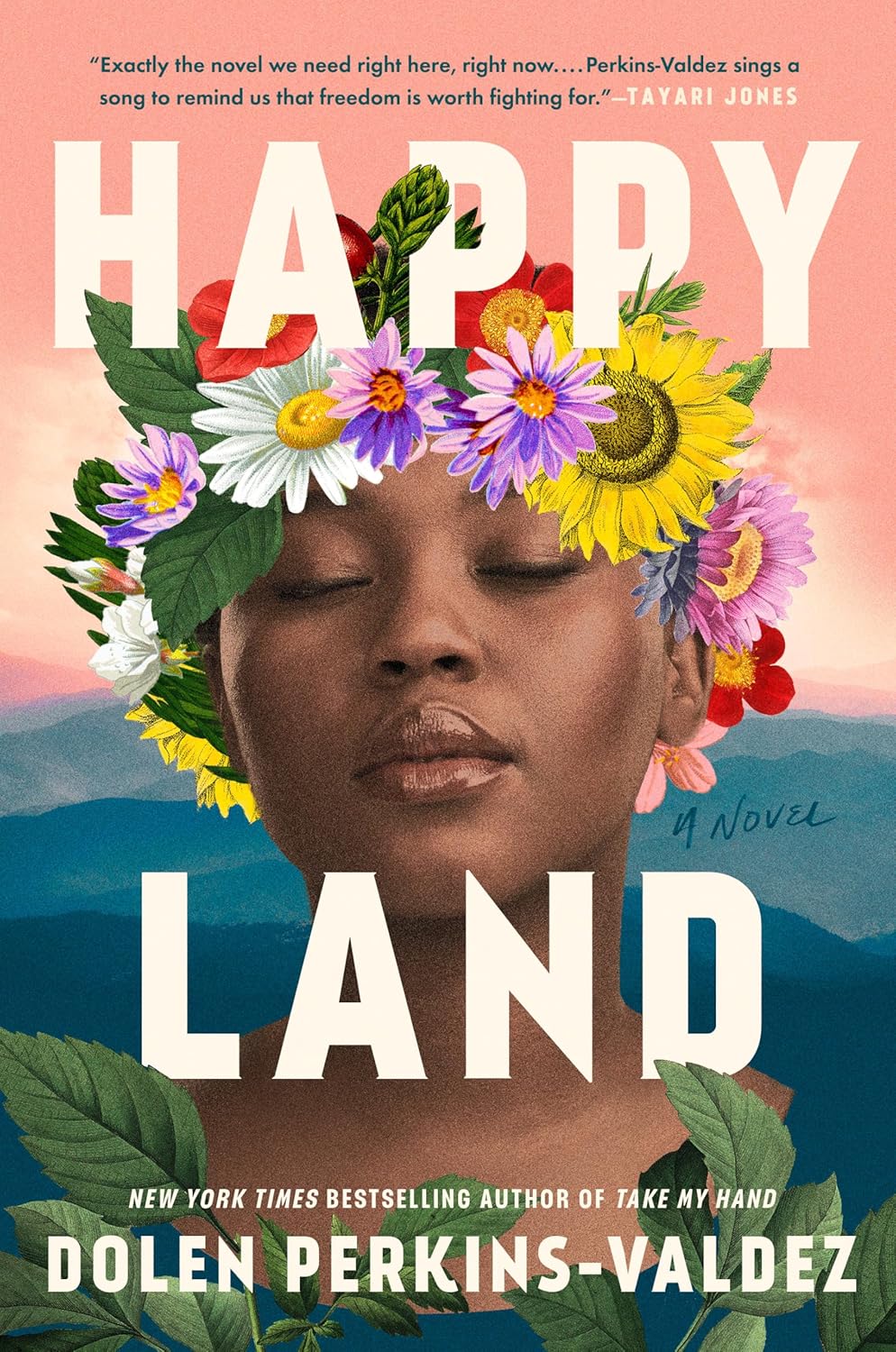

Happy Land: A Novel

- By Dolen Perkins-Valdez

- Berkley

- 368 pp.

- Reviewed by Wendy Besel Hahn

- April 21, 2025

A DC woman discovers she’s heir to a long-ago, real-life Black kingdom.

At a time when federal agencies are being ordered to delete American history from websites, reading Dolen Perkins-Valdez’s Happy Land feels subversive. In her author’s note, she shares the basis for her novel, found in archives: In 1873, a group of freedpeople settled near Zirconia, North Carolina, where they established a remote kingdom with a communal treasury and named a queen and a king. They eventually purchased 205 acres in the Blue Ridge Mountains; Luella and Robert Montgomery’s names appear on two deeds to these lands divided between North and South Carolina. Happy Land resurrects these freedpeople and their community.

Perkins-Valdez’s protagonist is the great-great-great-granddaughter of Luella, queen of the Kingdom of the Happy Land. The novel opens as Nikki Lovejoy, almost 40, arrives on Mother Rita’s land in North Carolina for the first time, completely ignorant of her identity. Mother Rita’s only child, Nikki’s mother, left the place behind at 18 to settle in Washington, DC, and start a family. The reasons for the generational rift remain murky.

Once Nikki hears about the kingdom and her connection to it, she recognizes what she has lost due to the estrangement between Mama and Mother Rita:

“Now here I am walking beside my grandmother on acres and acres of land that my people have inhabited for over a hundred years. It’s hard to put how I’m feeling into words other than to say I’m dizzy with grief. I didn’t know you could mourn something you never had.”

The story of the kingdom unfolds in alternating chapters and has parallels with Biblical accounts of Moses. After the abolition of slavery, Klansmen lynched freedpeople who dared to exercise their new right to vote in Cross Anchor, South Carolina. When Luella’s Papa, a Black preacher, registered people to vote, he became a target. Brothers William and Robert Montgomery led Papa’s church out of the Klan stronghold to a place of safety. Their Canaan lay beyond the reach of the U.S. government, or so they believed.

This backstory propels the narrative forward as Nikki learns more about her ancestors. Once Luella marries William Montgomery and becomes queen, she advocates for women to have two spots on the kingdom’s council. Women insist on building a school and starting a business making liniment.

Like most of the women in the novel, Queen Luella has complex marital relationships. William abandons her after suffering an accident in the mines. When it becomes clear he has no intention of returning, Luella embraces Robert as an unofficial second husband, and he becomes the de facto king. Together, they have two children.

Out of economic necessity, freedpeople and their families seek jobs beyond the kingdom. Industrialization further endangers the kingdom as railroads move white civilization closer, encroaching on their way of life. At one point, Luella and Robert turn over the deeds to their land in exchange for their son’s very life, with the hope of purchasing it back.

As the modern-day plot develops, Nikki must save the Kingdom of the Happy Land and enlists legal help to fight her grandmother’s eviction and dispute the continued transfer of property. Explains Perkins-Valdez, “This history of African American industriousness is often overshadowed by what followed.” She goes on to cite conservative estimates that, between 1910 and 1997, African Americans lost $326 billion in land wealth.

Initially, I experienced a sense of loss as the kingdom dwindled from 205 acres to four. The denouement felt like defeat. The kingdom, refreshingly, is not a country where white folks craft laws to enforce racial discrimination. Instead, it’s an upside-down mountaintop world where people, not wealth, are valued. Where one 15-year-old African-American boy is worthy of monetary sacrifice.

Ultimately, I surrendered to Nikki’s joy over those four acres. “I will plant lots of flowers,” she remarks in the book’s epilogue. “I will be the great-great-great-granddaughter of Queen Luella’s dreams.” Like those freedpeople who once journeyed from Anchor Cross up the Blue Ridge Mountains, the heir to the kingdom has an uphill climb. Yet reading Happy Land felt like the antidote to watching the national news. It’s a reminder to view current events through a wider lens. And to dream.

Wendy Besel Hahn is the nonfiction editor for Furious Gravity, an anthology of 50 women writers in the Washington, DC, area. Her work appears in the Washington Post, HuffPost, Hippocampus, Sojourners, and elsewhere. She lives and writes in Denver, Colorado.