Here Beside the Rising Tide: Jerry Garcia, the Grateful Dead, and an American Awakening

- By Jim Newton

- Random House

- 528 pp.

- Reviewed by Daniel de Visé

- August 20, 2025

The low-key frontman embraced — but never sought to lead — the counterculture.

Back in the 1960s, the Grateful Dead weren’t even regarded as the best band in San Francisco. That honor went to the Jefferson Airplane, who headlined the second day at Woodstock, albeit at 8 a.m. on day three. More than half a century later, the Dead loom large on the American music scene — larger, perhaps, than any other band of their era, from Frisco or anyplace else.

I don’t know of another American rock band that has been the subject of more books: a veritable shelf-load, including collections of stories and pictures, annotated lyrics, business studies, scholarly tomes, and even a book about the Dead’s sound system that somehow reached the New York Times bestseller list this year.

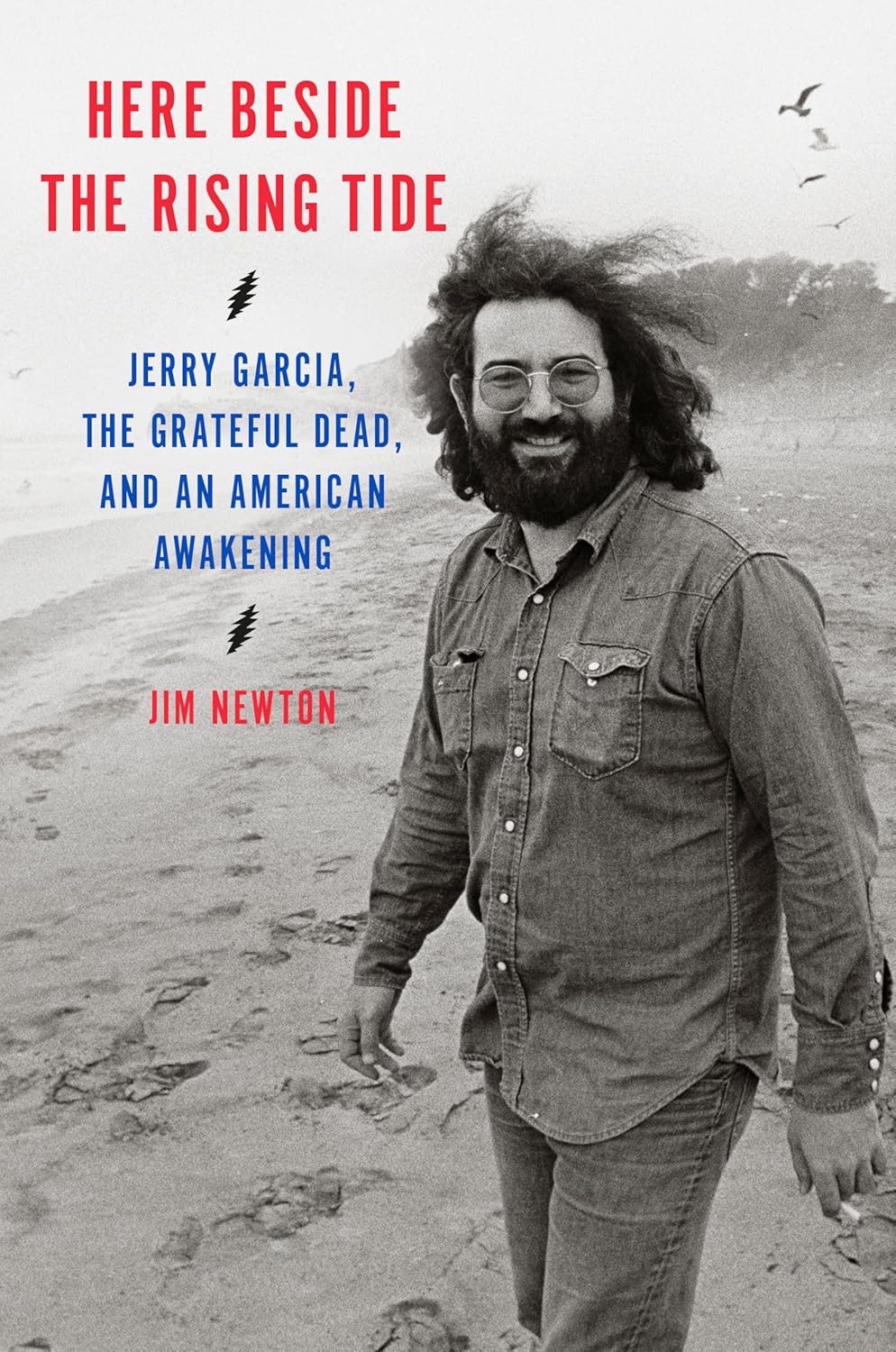

Now, into that fray comes Here Beside the Rising Tide, a biography of Jerry Garcia penned by Jim Newton, a longtime Los Angeles Times journalist. In selecting Garcia as his subject, rather than the band as a whole, Newton wisely skirts most of the Dead books on the aforementioned shelf. There’s only a handful of prior Garcia bios, most notably Garcia: An American Life, published back in 1999 by Blair Jackson, one of a few Dead scribes who serve as more or less official historians of the band.

Garcia was the Dead’s reluctant leader, a man who wanted to spend every waking hour playing the guitar. The band’s singular approach to musical performance reflected his vision of life as one long improvisational solo.

Garcia is, or should be, a towering figure in American musical history, probably on a par with Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen, James Brown and Aretha Franklin. But Garcia had none of their ego and no wish to lead, so he cocooned himself within a band.

Does the world need another volume about him and the Dead? Maybe so. I’ve read a few of the others. They’re good books, thoughtfully written, but most seem to exist within an insular Deadhead bubble. They look and read like portraits of a cult band, written by Deadheads for Deadheads. But there are exceptions. David Browne, a longtime Rolling Stone writer, penned the excellent So Many Roads, published in 2015 and written from a perspective outside the Grateful Dead universe.

Newton’s book, too, clearly aims for an audience beyond Deadheads, starting with its cover art, which pictures an unadorned Garcia on a beach, with no trace of skeletons, lightning bolts, dancing bears, or blood-red roses.

One quality that sets Newton apart from most prior Dead biographers is his reportorial depth. Journalists have a skillset that historians sometimes lack: They’re more likely to consult sources beyond the official canon — including news clippings, court records, police reports, and voices from outside the bubble.

Garcia remembered watching his father die, drowning in a river in 1947. But Newton the journalist scanned local papers from that day and found no reference to a child’s presence at the scene, politely pushing back on Garcia’s memory.

In another anecdote, members of the Dead recalled someone spiking the coffee with LSD at a 1969 TV appearance with Hugh Hefner. Newton reviewed subsequent correspondence between the band and the production team, which makes no reference to any transcendental incident. He concludes, “It seems more likely lore than true.”

Newton isn’t a music writer, per se. I remember him as a superb police reporter at the L.A. Times in the O.J. era. And he’s written books about Eisenhower and Earl Warren. Here, he delivers a sociopolitical work about a musician. His thesis: The man and his band led and shaped the counterculture in its decades-long battle against various police departments and politicians. Newton shows the Dead playing a central role in many iconic gatherings of their era, from Ken Kesey’s Acid Tests to the big rock festivals at Monterey, Woodstock, and Altamont.

The book posits Ronald Reagan as Garcia’s nemesis and the staunchest opponent of the counterculture, first as California governor and, years later, as president. The counterculture and its battles, in fact, provide a strong counternarrative to Garcia’s story, and Newton is an astute historian. He describes Reagan’s gubernatorial campaign and the Acid Tests circling each other, “competing for adherents.” He portrays the Dead lying “at the center of California politics” in the late 1960s and posits Reagan and Garcia as opposing forces, each fighting for his own brand of “freedom.”

Garcia and the Dead sought their freedom in collective expression, coming together as a community to do, play, sing, and ingest what they wanted. Reagan sought a different sort of freedom, individual, and grounded in the language of escape — from tyranny and persecution at the hands of an overreaching government or a lawless citizenry. Both Garcia and Reagan, Newton writes, “would take their fight from California to Washington and beyond.”

Is that a stretch? Garcia and the Dead were hardly household names in the late 1960s: No Dead song touched the Billboard charts until 1970. And yet, the band certainly sat at the center of the counterculture in San Francisco. And Newton makes a good case that the Dead kept the counterculture alive through the Reagan ‘80s, their shows and vast community a beacon of hope for those who rejected Reaganomics.

One thing that makes the Dead so interesting is that the band kept getting bigger and bigger in the Reagan era, though most of its best work lay many years past. Newton notes that the band was the second-highest-grossing musical act of 1985, scored its first Top 10 hit in 1987, and staged the largest concert tour of 1993.

Newton is a great writer, and I breezed through Here Beside the Rising Tide. But I have two quibbles. First, the book struck me less as a Jerry Garcia biography than a bio of the full band. After the second chapter, the story moves freely among Garcia and his bandmates, never dwelling too long on the reluctant leader himself.

My other observation, not necessarily a criticism, is that Newton’s book isn’t really about music. When he discusses the songs, he mostly parses their lyrics. And that’s fine: They’re great lyrics. But Garcia didn’t write most of them. The Dead employed a full-time lyricist, Robert Hunter. A reader can learn plenty about the Dead by reading Hunter’s lyrics but not so much about Jerry Garcia.

Of course, many other great writers have delved into what made Garcia such a brilliant guitarist and songwriter. Browne, of Rolling Stone, is one. Newton quotes another, Jon Pareles of the New York Times, on Garcia’s legacy: “There was no aggression in his solos, and even when he picked up speed, he phrased with the relaxed tickle of a bluegrass guitarist,” Pareles wrote in 1995. “His most characteristic mannerism, sliding down a few frets, was the sonic image of someone slipping out of the spotlight.”

Throughout their three-decade career, the Dead never really crossed over into mainstream American culture. Much of society viewed them and the Deadheads as a hippie cult, albeit a very large one. And that, I think, is why the Grateful Dead never merited serious consideration as one of the great American musical acts, an honor they deserve. Newton recognizes that, and his Garcia biography is a step in the right direction.

Daniel de Visé is the author of five books, including The Blues Brothers: An Epic Friendship, the Rise of Improv, and the Making of an American Film Classic.