History Matters

- By David McCullough; edited by Dorie McCullough Lawson and Michael Hill

- Simon & Schuster

- 192 pp.

- Reviewed by Kitty Kelley

- October 6, 2025

The celebrated late historian’s advice to writers.

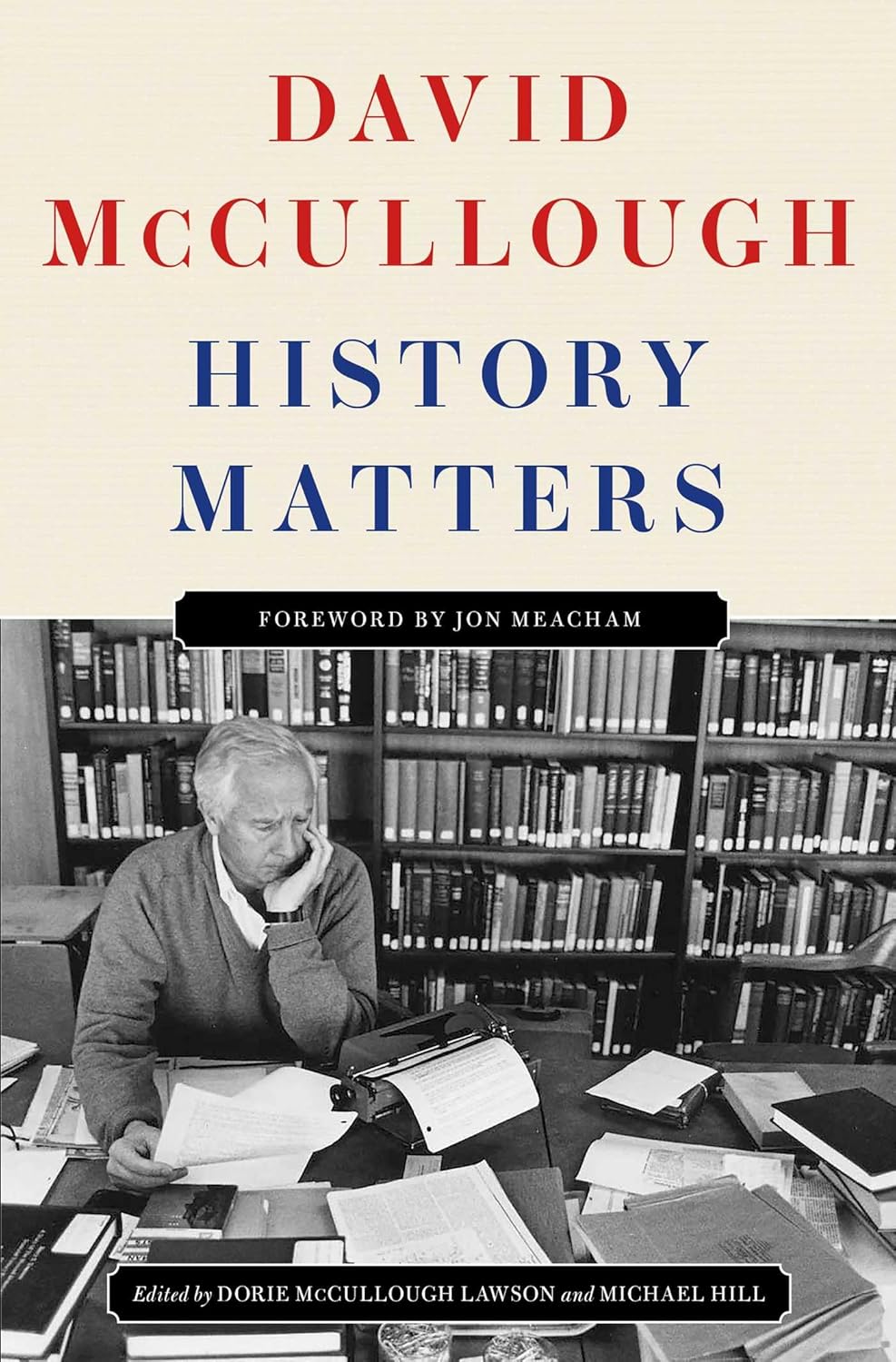

Any book carrying the name of David McCullough usually weighs three pounds less than a horse. His first biography, Truman, ran to 1,120 pages; his second, John Adams, weighed in at 751 pages. Both won the Pulitzer Prize. Prior to those, in 1978, McCullough received the first of his two National Book Awards for The Path Between the Seas: The Creation of the Panama Canal, 1870-1914 (704 pages). An earlier book, 1972’s The Great Bridge: The Epic Story of the Building of the Brooklyn Bridge, spanned 600+ pages. Here was a writer who understood the heft of history — or, as the New York Times wrote in McCullough’s 2022 obituary, “His readers got a lot of work for their money.”

Now comes his daughter Dorie McCullough Lawson and his researcher Michael Hill with a book entitled History Matters. For those accustomed to a McCullough whale, prepare for a polliwog: This book is a mere 192 pages. Most puzzling is its preface, which tells readers what they are not going to get:

“This book is by no means exhaustive and there are certain areas of his work, his life and his personality that are not covered, including, among other things, his disciplined way of approaching everything, his love of walking and walking sticks, his insistence on things being done in particular ways, his love of lyrics and quotations and his readily available humor.”

Instead, Lawson and Hill offer speeches and essays, some previously published, that the historian delivered on various subjects — including his love of architecture and the glories of San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge and Brunelleschi’s dome in Florence — which led him to ruminate on what he felt was lacking in American education. “The first is imagination, originality, spontaneity…The second is willingness to take risks.” From there, the applauded historian celebrated “luck, effort, and, above all, work: ‘We are what we do.’”

From an early age, Pittsburgh native David Gaub McCullough, the third of four sons, knew he wanted to be a writer, although he’d once considered a career in architecture. After graduating from Yale (class of ’55), he moved to New York City and worked for Sports Illustrated for five years. Then, in 1960, he relocated to Washington, DC, to work at the U.S. Information Agency under the revered CBS journalist Edward R. Murrow. “It was like having a part in a hit show, with a huge cast,” McCullough told the Yale Daily News in 1997, “and even if you only had a bit part, it was still very exciting.”

McCullough, whose sonorous voice narrated the award-winning 1990 Ken Burns PBS series “The Civil War,” seemed to be a gregarious man who needed to share his love of learning, as well as his strong opinions. He praised George Washington as the “greatest American ever”; dismissed Pablo Picasso as “dislikeable”; and defined Richard Nixon as “an absolute disaster.”

In this short book, McCullough advises anyone who wants to be an author to write four pages a day, every day. He stresses doing research: If writing a biography, walk the streets that your subject walked, whether it’s in a Kentucky coal town, the jungles of Panama, or the boulevards of Paris. He recommends taking drawing lessons because he believed writers needed such basics in order to write well. “I think of writing history as an art form.”

He suggests developing the habit of asking people about themselves — their lives, their interests — “and listen to them. It’s amazing what you can learn by listening.” Finally, he counsels writers to “read a lot” and makes sterling recommendations, including President John F. Kennedy’s favorite book, The Young Melbourne, by David Cecil, as well as Barbara W. Tuchman’s The Proud Tower; Bruce Catton’s A Stillness at Appomattox; Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr.’s The Autocrat of the Breakfast-Table; Tobias Smollett’s The Expedition of Humphrey Clinker; William L. Shirer’s The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich; Cecil Woodham-Smith’s The Reason Why; Walter Lord’s A Night to Remember; and even Dr. Seuss’ Horton Hatches the Egg.

In the 40 commencement speeches he delivered over the years to various college graduates, McCullough always advised them to read. “Read Delacroix. Don’t just look at him. Read him. Read his journal — one of the most enthralling books I know. Read Churchill. Read history. Read, read, read. Read Trumbull’s memoir. Read the letters of N.C. Wyeth, the magnificent letters of N.C. Wyeth to his children.” Most important of all, he counsels writers to:

“Rewrite, rewrite, and rewrite. When asked if I’m a writer, I think sometimes I should say, ‘No, I’m a rewriter.’”

Here is where the authors miss the brass ring on their merry-go-round. McCullough never used a word processor or a computer. He did all his work and all those rewrites on a typewriter, much of which he saved. His daughter mentions a storehouse of his “letters, calendars, multiple evolutions of original manuscripts with his hand-written editorial changes, ideas, notes, lists, diagrams, paintings, drawings and photographs…” Yet she doesn’t excavate that mine for its vein of gold, which seems like a missed opportunity to share all that her father shared in his creative-writing classes at Wesleyan, Cornell, and Dartmouth.

How valuable it would have been for readers to learn how the heralded historian wrote and rewrote; how he started; what he added; what he deleted; what he expanded. How did he edit himself, develop scenes, and construct chapters? Did he outline before writing? How did he organize his material? Did he make a chronology of dates and events? How did he decide what belonged to history? What could be discarded?

Ah, yes. A master class from a master is a writer’s ultimate fantasy and nearly impossible to convey in any book. Still, the authors of this one, however slight, manage to give a glimpse into what they call “the good, hard work of writing well” by a master craftsman who never toiled a day in his life. David McCullough wrote and rewrote, then rewrote and rewrote his 12 mammoth books simply because he loved every agonizing minute of the writing adventure.

Kitty Kelley is the author of seven number-one New York Times bestseller biographies, including Nancy Reagan, Jackie Oh!, and Elizabeth Taylor: The Last Star. She is on the board of the Independent and is a recipient of the PEN Oakland/Gary Webb Anti-Censorship Award. In 2023, she was honored with the Biographers International Organization’s BIO Award, which is given annually to a writer who has made major contributions to the advancement of the art and craft of biography.

.png)