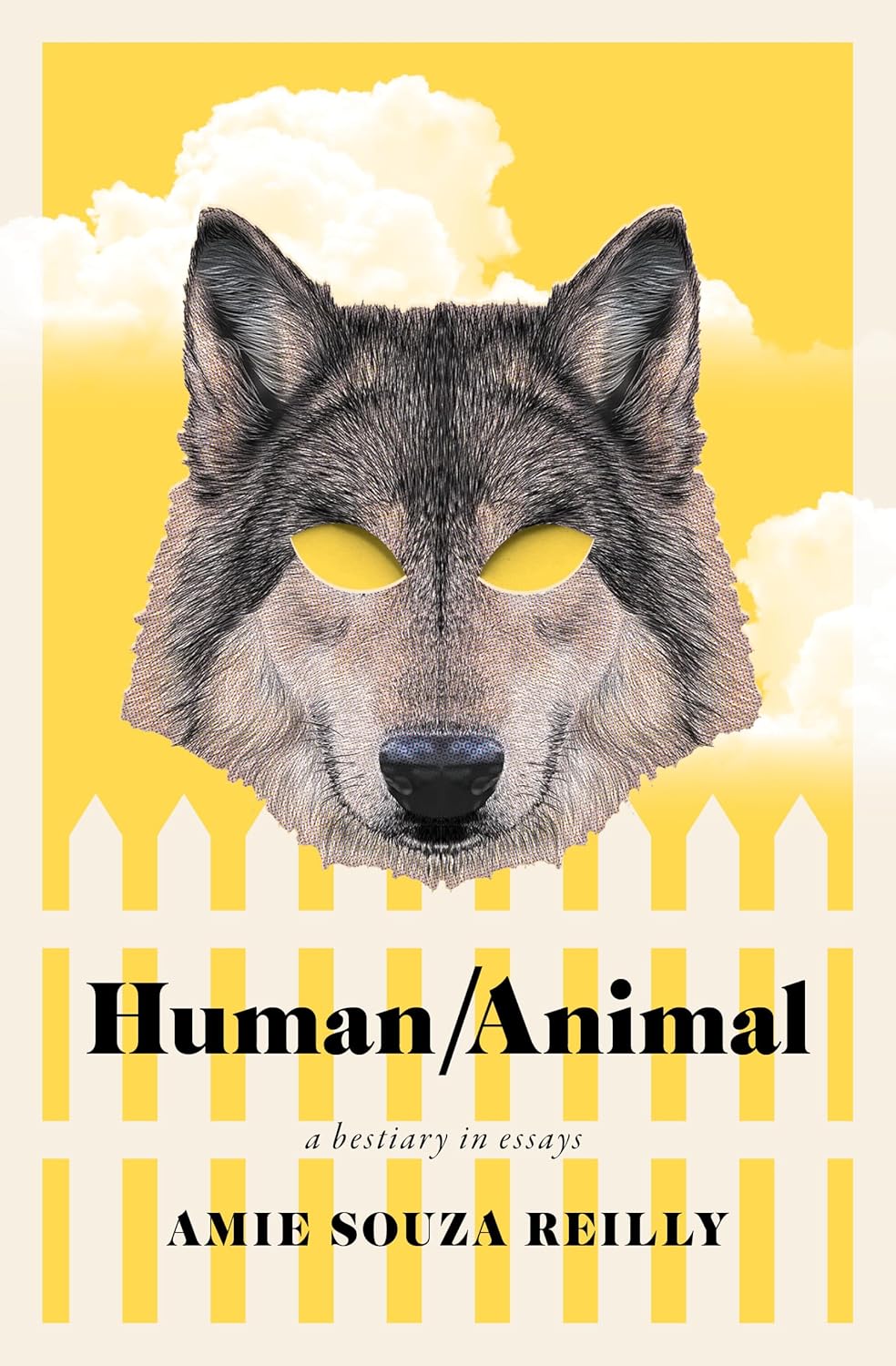

Human/Animal: A Bestiary in Essays

- By Amie Souza Reilly

- Wilfrid Laurier University Press

- 194 pp.

- Reviewed by Yelizaveta P. Renfro

- May 14, 2025

This incisive hybrid work plumbs what it means to be afraid.

Amie Souza Reilly’s Human/Animal: A Bestiary in Essays opens with a description of the home that she and her family moved into in August 2014. “An old white house with green shutters,” it had “hardwood floors and leaded glass windows” and was within walking distance of both the train station and the beach. Newly remarried and starting graduate school, Reilly was poised on the brink of a new life that seemed nearly idyllic, and then she drops a bombshell at the bottom of the first page: “For the first three years we lived here, we were stalked.”

The two brothers, Wes and Jim, who owned the house next door began to harass Reilly, her husband, and her 6-year-old son soon after they moved in. “In the beginning, there were no overt threats, but they stood too close, said peculiar things, stood in our yard uninvited and stared,” she writes, noting that she felt afraid of the brothers from her first encounter with them.

What follows is the story of what happened over the years that the brothers tormented Reilly and her family, interwoven with philosophical meditations on boundaries, fear, surveillance, paranoia, revenge, and other topics, as well as short, illustrated entries of a modern-day bestiary. The hybrid, experimental nature of the text — part memoir, part cultural criticism, part bestiary — makes for an eclectic and provocative reading experience.

The 35 bestiary entries sprinkled throughout the book’s 10 chapters don’t always have obvious, explicit connections to the material surrounding them. “The animal entries in this text form a linguistic history within my lived history, not disrupting the text so much as supporting it,” Reilly explains in the first chapter. “There is something I can learn from these animals, how we treat and have treated them, not just corporeally, but in language.”

She is interested not in the noun but in the verb form of common animal words — for example, to badger, to ape, to parrot, to squirrel, to fish, to ferret, and so forth — exploring how such usages say a great deal more about humans than they do about the animals from which they derive.

Reilly’s entry on the verb form of cow quotes Samuel Johnson’s definition, “to depress with fear,” to which she adds, “to dispirit, overawe, intimidate.” To gander means both “to wander aimlessly, in body or in speech” and “to look at, as in ‘take a gander.’” Reilly adds, “Looking can be violent, as in staring. The ‘taking’ of a look also implies a lack of consent.” Though she doesn’t mention herself or the brothers in her definitions, the connections are often obvious. And she notices something more about our use of animal nouns as verbs:

“Almost every animal, when reconsidered into its verb form, defines an act of violence, labor, or motherhood.”

One day, as the situation with the brothers escalates, Reilly, having just pulled into her driveway, is faced with a terrifying sight. “I heard a damp bump on my window, loud as the smack of rotted fruit,” she writes. “Wes had his hand pressed against the glass, hard enough that his flattened fingers appeared yellow and bloodless.” The man then proceeds to harangue her about her rudeness for not waving in a friendly manner at the brothers (who had been on their front lawn) and her unfitness as a mother. “My son and I sat silent in our seats, safe, but precariously close to unsafe, like two Jonahs in a whale,” Reilly writes. Later, perhaps to place some distance between herself and the terrifying encounter, she retells the story as a fairytale:

“Once upon a time there was a family. A mother, a stepfather, and a little boy. The family moved to an old white house in a suburb near the sea. Next door to the family lived two brothers, strange strangers who wandered the streets, dropping trash and sticks wherever they went…One day the mother took her boy out for ice cream and the day was so beautiful she forgot to be afraid. When they returned home, she didn’t notice the shadow coming around the driveway until the taller, meaner brother trapped her and her little boy in the car with his big hands. It was then when she realized how much stronger he was, how wild his eyes were, and she pulled and she pulled on the door to keep her little boy safe.”

Though the brothers never inflict any bodily harm on Reilly or her family, the specter of fear eventually begins to control her life. “They should not have followed us, mowed our lawn, rifled through our compost, stolen the survey stick, dumped yard debris onto shared space, hollered at me, my husband, my mother, trapped me in my car, shone a flashlight into our yard, or watched us over the fence,” she writes. As she examines her reactions to the brothers’ actions, Reilly realizes that gender and race are implicated in fear:

“Instilling fear is a way of maintaining power, or extracting more power, or removing someone else’s power. Fear is meant to be constant because it is integral to patriarchy and white supremacy, underpinning traditions of oppression and containment. My fear is mine and is also part of a collective consciousness, held by many folks living outside of a cisgendered straight White male identity. I am a cisgendered White woman and so have tremendous privilege, though still feel this fear. Like an electrical undercurrent to our existence, the longer it’s felt, the more we grow accustomed to it.”

Reilly’s terror balloons following another altercation. After the brothers park their car in Reilly’s driveway, blocking her in, and she summons the police, Wes falls to the ground in front of the officers, and an ambulance is called. As he is lifted onto a stretcher by paramedics, he shouts at Reilly, threatening to sue her. “I had scared him, he kept saying, my yelling scared him so much he tripped on the sidewalk crack,” Reilly writes. “I kept telling them to fix that, he said, and now I am having a heart attack.”

Now, Reilly fears legal retribution on top of the usual harassments. Though a different neighbor tells her that Wes’ apparent heart attack was “a ruse,” she still cannot escape the grip of her fear. “Every car door, every man’s voice outside, every baseball hat, every unfamiliar piece of mail became a possibility of their return or a summons or a court date,” she writes. “I didn’t even know if they had any grounds to sue us, but we had so much to lose that even the possibility sent my thoughts spiraling. It seemed impossible to move forward.”

In the end, it is the fear of what might happen — rather than what actually does happen — that proves the far greater torment. In a roving narrative that takes us into a host of topics — horror movies, gaslighting, the wilderness, consumption, pain, cannibalism, motherhood, and vegetarianism, among others — Reilly tries to make sense of the three years she suffered at the hands of Wes and Jim. She writes:

“I can’t get to the truest story of the neighbors without aligning them, or what happened, with something else, something not-them. I turned to lanternflies like I turned to rhinos, poems, horseshoe crabs, performance art, bug collections, elephants, horror films, and art. Like I turned to animal verb etymologies. I am looking wherever I can for reasons. The rhinos, poems, horseshoe crabs, performance art, bug collections, elephants, horror films, and art function as metaphors do — comparisons getting closer to what I can’t get to otherwise. And then, as I work to comprehend the brothers’ actions, I understand them as part of something larger, though seeing them as symbolic of settler colonialism seems more literal. Their behavior was both unlike anything I had seen before and exactly like everything I had seen before.”

In other words, Reilly’s situation becomes a microcosm for a much larger pattern of ills within our society. Her book is guided more by the meandering path of her reflections and etymologies than by the specifics of her conflict with the neighbors. In the end, the particular wrongs of the brothers matter much less than Reilly’s meticulous processing of them. Readers looking for a wide-ranging meditation on our country’s political climate and a host of other issues will find much food for thought here.

Yelizaveta P. Renfro is the author of a book of nonfiction, Xylotheque: Essays, and a collection of short stories, A Catalogue of Everything in the World. Her fiction and nonfiction have appeared in Glimmer Train Stories, Creative Nonfiction, North American Review, Colorado Review, Alaska Quarterly Review, South Dakota Review, Witness, Reader’s Digest, and elsewhere. She holds an MFA from George Mason University and a Ph.D. from the University of Nebraska.