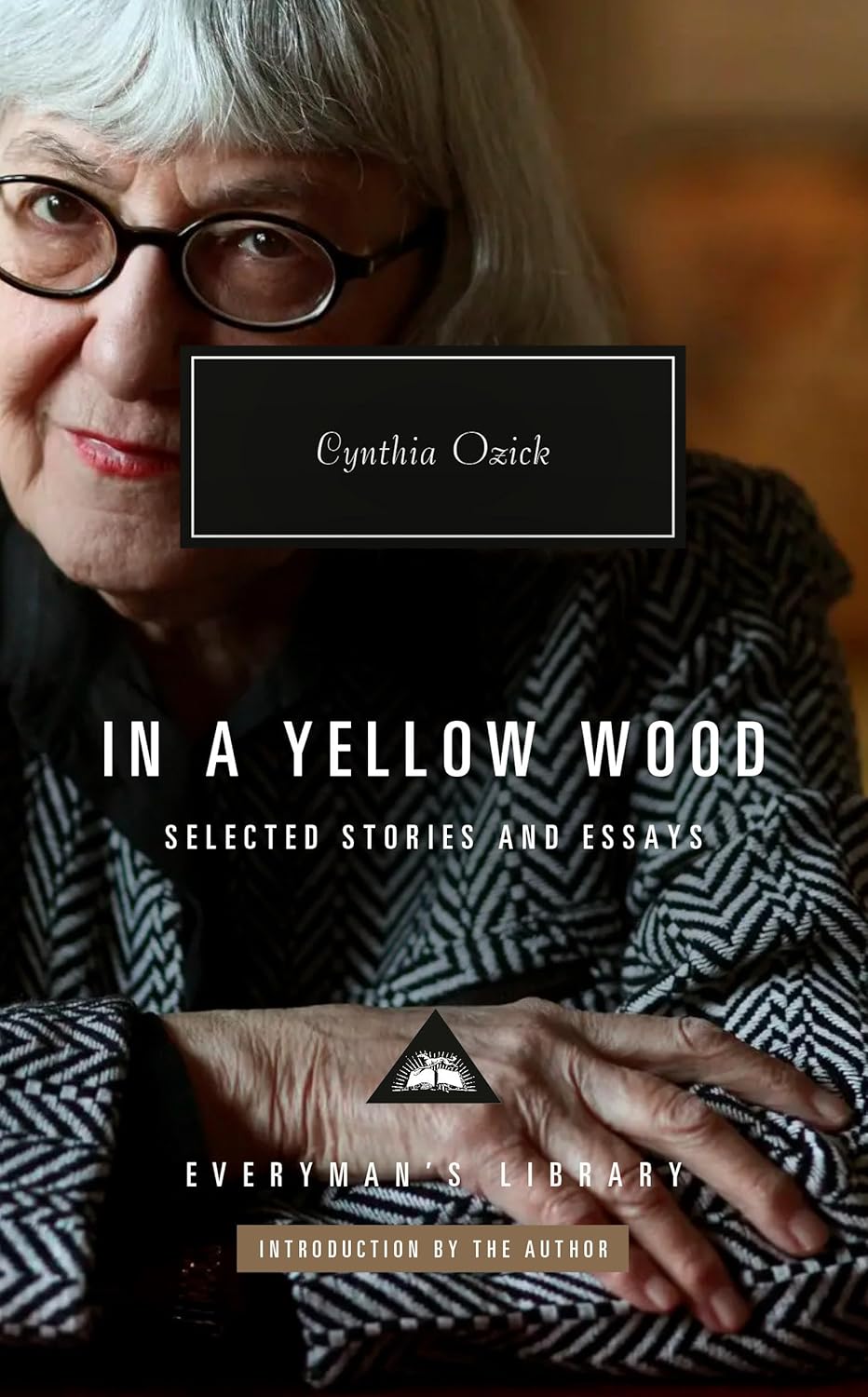

In a Yellow Wood: Selected Stories and Essays

- By Cynthia Ozick

- Everyman’s Library

- 712 pp.

- Reviewed by Karl Straub

- June 4, 2025

An outstanding introduction to the master’s body of work.

Cynthia Ozick has become known for two types of sentences: the rain-filled kind that flows through her fiction, cakey stream into river, river into venerable ocean, and (across town) in her immortal essays, the other kind — often grim — with which she pronounces on departed writers, forgotten luminaries, and burnished shibboleths.

To describe these Ozickian sentences as “well-crafted” is to mistakenly file them among the small beer and delicates, for her prose yardages (in the stem-winding manner of her beloved Henry James) are more than just a mundane job well done. Her Jamesian combination of linguistic prowess and sociological insight is on such an elevated plane that it skates eerily close to verbal mysticism.

Ozick was denied the validation of appearing in print for much of her youth; having lived for nearly a century, she now denies time and gravity, continuing to write the highest-quality prose at an age when most of us are dead. And her early sidelining paid an interesting dividend; reading them together in the new collection In a Yellow Wood, it’s hard to tell which pieces are old and which are young.

For artists of prodigious facility, there’s always the danger that critical focus on their virtuosity will obviate a serious consideration of their themes and the philosophy underlying their aesthetic concerns. This is a risk with Ozick, as it is with William Faulkner, James, and (in a very different field) saxophonist Charlie Parker. With artists like these, the technique is always white-hot and never more than briefly eclipsed.

Ozick’s prose, as baroque and flexible as a Bach melody line, is gloriously abundant in this assemblage. Here are a couple samples to whet the appetite of an Ozick newcomer. These passages are overwhelmingly thick with life and rhythm and color; to absorb it all, today’s Ozick novice is likely to become tomorrow’s Ozick re-reader. In “Virility,” she writes:

“He headed back for his cellar and I happened to notice his walk. His thick round calves described forceful rings in his trousers, but he had a curiously modest gait, like a preoccupied steer. His dictionary jogged on his buttock, and his shoulders suggested the spectral flutes of a spectral cloak, with a spectral retinue following murmurously after.”

And in “Usurpation,” she opines:

“Cheats and fakes always hunt themselves up in stories, sniffing out twists, insults, distortions, transfigurations, all the drek of the imagination. Whatever’s made up they grab, thick as lawyers against the silky figurative…Stories came from me then, births and births of tellings, narratives and suspenses, turning-points and palaces, foam of the sea, mermen sewing, dragons pullulating out of quicksilver, my mouth was a box, my ears flowed, they gushed legends and tales, none of them of my own making, all of them acquired, borrowed, given, taken, inherited, stolen, plagiarized, usurped, chronicles and sagas invented at the beginning of the world by the offspring of giants copulating with the daughters of men.”

The theme that runs through much of her work is the awkward human tendency to paper over the truth of identity and history. She most often locates this covering and subsequent uncovering in the material of Jewish life, but as much drama and tragedy as she’s found there, an avenue is an avenue. Her theme often wears, in a sense, a Jewish mask; its real identity is humanity.

She is at some pains, both in the collection’s introduction and in its substantial short-story offerings, to push back against the canard that she is primarily an essayist. Certainly, the bushel of fine-grained fiction makes a compelling argument for seeing her as one of America’s premier storytellers, but her essays are justly celebrated even more.

Ozick says an essay is “a short story told in the form of an argument,” and her approach to the form presents a fascinating paradox. Her force of argument — in essays about Anne Frank, Kafka, Helen Keller, Dostoevsky, and the essay form itself — is strong enough to batter a coastline, but she resists the cheap sentiment and manipulation of the polemic. Regardless of subject, her eternal investment is in the prose itself. As she writes in “She, Portrait of the Essay As a Warm Body”:

“The essay is by and large a serene or melancholic form. It mimics that low electric hum, sometimes rising to resemble actual speech, that all human beings carry inside their heads — a vibration, garrulous if somewhat indistinct, that never leaves us while we wake. It is the hum of perpetual noticing.”

No sampling of Ozick’s prolific output can tell the whole story, but this well-curated collection is a good place to start. It should be considered indispensable.

Karl Straub studied music education at Howard University and writes about music, books, film, and TV at karlstraub.substack.com. He lives in Alexandria, Virginia.

.png)