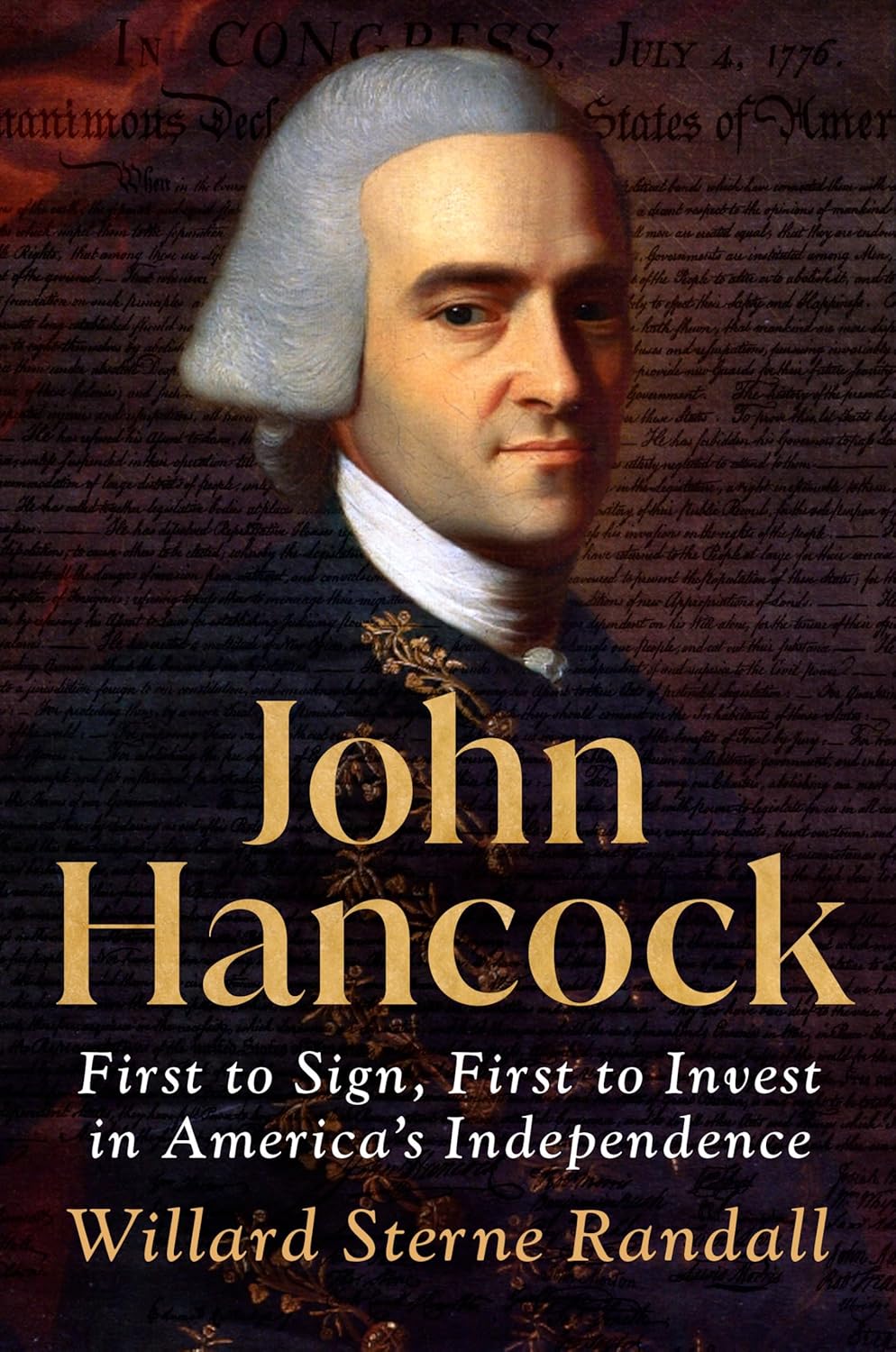

John Hancock: First to Sign, First to Invest in America’s Independence

- By Willard Sterne Randall

- Dutton

- 288 pp.

- Reviewed by Stephen Case

- August 4, 2025

This patriot deserves recognition for more than his penmanship.

Imagine the Revolutionary War as a film competing at the Academy Awards. Surely, George Washington would win Best Patriot. But who would take home Best Supporting Patriot? In his crackerjack new book, John Hancock: First to Sign, First to Invest in America’s Independence, acclaimed biographer Willard Sterne Randall convincingly stumps for Hancock. (Remember him? His supersize signature all but jumps off the Declaration of Independence.)

Although never officially a soldier nor an overseas diplomat, Hancock was both president of the Continental Congress and a multi-term governor of Massachusetts. After the Revolution, while dealing wisely with unhappy farmers in Massachusetts and finagling ratification of the Constitution, Hancock, despite frequent, disabling bouts of gout, continued laboring on his country’s behalf until his death, at 56, in 1793. His childhood friend, future president John Adams, wrote about him:

“I could melt into tears when I hear his name. [He was] benevolence, charity, generosity…personified…[He was a] steady, ready, punctual, industrious, indefatigable man of business. Not less than a thousand families were every day dependent on Mr. Hancock for their daily bread.”

Hancock was born in 1737 in Braintree, Massachusetts. His preacher father died in 1744, survived by John’s impecunious mother and three children (John was second). Hancock’s life transmuted from rags to riches when his mother entrusted him, at age 8, to his late father’s childless brother, Thomas, a wealthy businessman who had “emerged as one of Boston’s leading citizens.” This move, writes Randall, “transported John to a mansion atop Beacon Hill and the privileged status of adopted son and putative heir to one of colonial America’s wealthiest entrepreneurs.”

Uncle Thomas sent Hancock to Boston Latin School and, at 13, to Harvard. Despite weathering one punishment there for heavy drinking, Hancock graduated at 17. Upon his uncle’s death, Hancock became “one of the wealthiest men in colonial America.”

In 1765, Britain imposed the Stamp Act, whose nocuous effects on businessmen are skillfully described by the author. Collaborating at the time with John Adams’ cousin Samuel (from whom Hancock was later estranged owing to a falling-out over local politics), Hancock capably led Bostonians’ successful efforts to achieve its repeal.

Not giving up, Parliament, in 1767, passed the Townshend Acts, which Hancock opposed aggressively, and which resulted in the seizing of one of his many ships. In 1772, angry Rhode Islanders incinerated the ship, by then renamed Gaspee and pressed into service of His Majesty’s customs’ fleet. Taking place 18 months before the Boston Tea Party, this represented the first public destruction of British assets at the hands of nascent Americans.

Just before 1773’s infamous Tea Party began, Hancock addressed the restive crowd, although debilitating gout left him unable to physically participate in the mayhem. Nevertheless, in 1774, Crown prosecutors charged him with treason. Arresting Hancock, his fellow colonials believed, was one objective of the British raid on Lexington and Concord in 1775. Warned by Paul Revere, Hancock escaped and journeyed to Philadelphia for the Second Continental Congress, which elected him president (a position at which, Randall tells us, he worked assiduously).

That same year, at 38, Hancock married the decade-younger Dorothy Quincy. While she lived until 1830, neither of their two children survived past age 10.

In 1778, with the Revolutionary War well underway, a force of Continentals, French Navy, and Massachusetts militia sought to oust the British from Newport, Rhode Island. Hancock, by then governor of Massachusetts, nominally commanded the state’s militia. Owing to poor planning and worse coordination, the attack was a fiasco, although nobody then or now, notes the author, blamed Hancock for the failure.

Following the war, Hancock continued to serve as Massachusetts’ governor, finally retiring in 1785 after five terms (all of them plagued by his ever-worsening gout). His successor, James Bowdoin, oversaw a period of nasty unrest — the 1786-1787 Shays’ Rebellion — among disenfranchised, highly indebted farmers in the western part of the state that nearly exploded into civil war. When Bowdoin raised funds for a militia to put down the uprising, Hancock refused to contribute, decrying “any scheme to finance an army of mercenaries to fight against their fellow veterans of the Revolution.”

Nonetheless, Bowdoin’s hired force routed the rebels at Petersham, Massachusetts, in February 1787. Inspired by the massacre to return to politics, Hancock “won [the governorship] in a landslide…[with]…more than 75% of the vote.” He then pardoned the Shays’ Rebellion offenders, commuted sentences, and spearheaded reforms that restored calm in his state.

Overcoming personal reservations, Hancock led the effort for Massachusetts to ratify the fledgling U.S. Constitution in February 1788. This healed his 17-year rift with Samuel Adams, who enthusiastically joined Hancock in endorsing the document. Adams then ran for lieutenant governor on Hancock’s victorious ticket in the next election, and the two men served together. Upon Hancock’s death in 1793, Adams succeeded him as governor.

Stephen Case is a member of the Independent’s board of directors and serves as its treasurer.