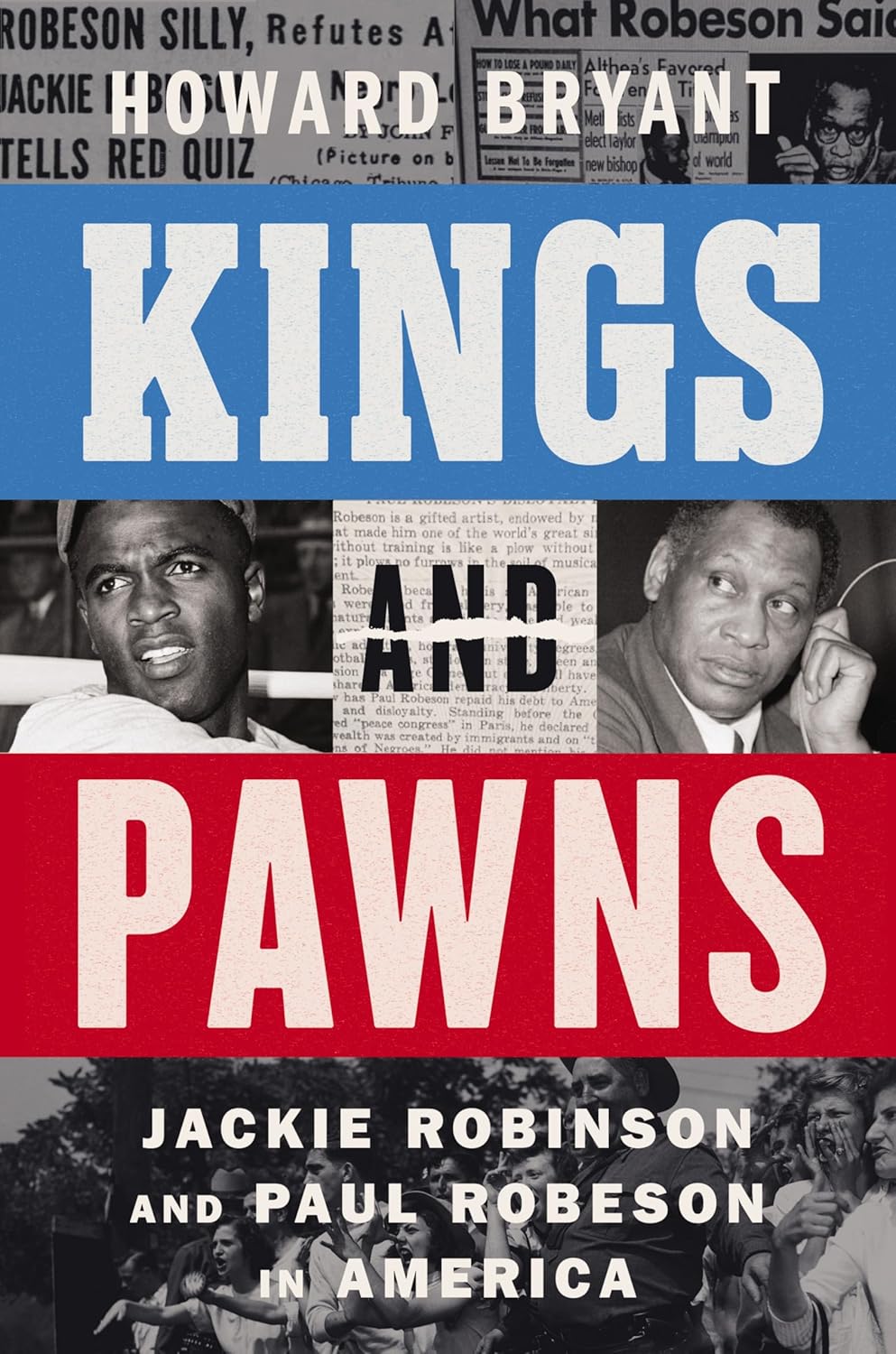

Kings and Pawns: Jackie Robinson and Paul Robeson in America

- By Howard Bryant

- Mariner Books

- 320 pp.

- Reviewed by E. Ethelbert Miller

- January 29, 2026

More than anything, the Cold War was a chess match.

On April 20, 1949, the Paris Peace Conference held its opening sessions. World War II was over, but the Cold War was heating up. The United States and the USSR, once allies, found themselves now in conflict and in pursuit of different political and economic goals. The mere mention of the word “communism” or “communist” created a Red Scare across America.

Singer, actor, and activist Paul Robeson spoke at the conference and remarked that American Negroes would never fight in a war against Russia. Those words would haunt him for the rest of his life. They would also create a divide within the Black community as white America looked for a well-known Black person to publicly reject Robeson’s views.

They found that person in legendary baseball player Jackie Robinson.

Howard Bryant, the author of several books about baseball, has carefully examined the politics that shaped America’s pastime during the 1940s and 1950s. In Kings and Pawns, he skillfully shows how Robinson’s and Robeson’s lives were intertwined and how both white people and the Black press used the two men to promote their own agendas. How Robeson and Robinson became pawns during the Cold War is at the center of this well-researched book.

Bryant notes a meeting that took place on December 3, 1943, at the Roosevelt Hotel in New York City between Major League Baseball’s 16 team owners and Robeson. At the time, Robeson was highly celebrated for his achievements in the theater, including for his role as Othello. He was also an outstanding athlete and felt that Black people were ready to play in the big leagues. Most of the owners, though, didn’t want Blacks to join their teams, but one exception was Branch Rickey of the Brooklyn Dodgers. His signing of Robinson — the MLB’s first Black player — was viewed as a great experiment, but Rickey was simply a business owner making a business decision. One which would prove profitable.

The integration of professional baseball during the Cold War coincided with the growing Civil Rights Movement in the United States. How could America be an advocate for equality around the world if Black people at home were denied it? The Robinson story was, therefore, more than a tale about a Black person playing on a white team; it was a symbol of success in America (and of the success of America). Robeson was similarly celebrated, at least until he made those controversial remarks in Paris. Was the famed performer really just a communist pawn?

To find out, the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) would eventually bring both Robinson and Robeson to Washington as part of its aggressive campaign to examine what it saw as “Communist Infiltration” into society. In 1949, Robinson was invited to testify before the committee. (Early drafts of his remarks were co-written by Rickey and biographer Arthur Mann.) Robinson didn’t directly criticize Robeson, but his mere presence before the HUAC in many ways made him a pawn, too. Bryant notes how Robinson’s wife, Rachel, even suggested some changes to his prepared testimony.

How loyal and thankful should Black people be to America? W.E.B. Du Bois wrote about the double consciousness of the souls of Black folk in 1903. Robinson and Robeson, like many Black people, wrestled with American acceptance and rejection. During the Cold War, the federal government tried to place a veil over incidents like the murder of Emmett Till in Mississippi in 1955. And FBI head J. Edgar Hoover believed the Civil Rights Movement was led by communists and used the agency to keep tabs on various Civil Rights leaders — especially Robeson.

Not surprisingly, Robeson was defiant when he testified before the HUAC in 1956, invoking the Fifth Amendment 30 times during the 60-minute hearing. Although his testimony was completely different than Robinson’s, both men sadly paid a price for having their names linked. By the end of the 1950s, their health had deteriorated, and years would pass before their reputations were restored.

Kings and Pawns, then, is also a cautionary tale. How many Black leaders have been forced to navigate America’s racial chessboard? Near the end of the book, Bryant writes about Moses Fleetwood Walker:

“Walker was the Oberlin- and University of Michigan-educated catcher who would become the first Black player to play in the professional circuit eventually known as Major League Baseball. Fourteen years before Robeson’s birth and sixty-three years before Robinson’s historic debut, Walker played in the primitive days of baseball...”

In 1908, Walker published “Our Home Colony: A Treatise on the Past, Present and Future of the Negro Race in America.” Unlike Robinson and Robeson, he understood his country well enough to embrace some of the teachings of Marcus Garvey. Like Garvey, Walker felt Africa, not America, might be the solution to the racial question.

One reads Kings and Pawns while reading and listening to the daily news. How welcome in this country, even now, are people of color? As we begin to celebrate the 250th anniversary of the founding of our nation, both Robeson and Robinson would likely agree that there’s much work still to be done. Black people have been playing checkers for too long. When will we master chess?

E. Ethelbert Miller is the author of two memoirs and several books of poetry. For 17 years, he served as the editor of Poet Lore magazine. He hosts the weekly WPFW morning radio show “On the Margin.” He was inducted into the Washington, DC, Hall of Fame in 2015 and received the 2016 George Garrett Award for Outstanding Community Service in Literature. Miller was given a congressional award from Congressman Jamie Raskin in recognition of his literary activism, and he was a Spoken Word and Poetry album Grammy finalist in 2023.