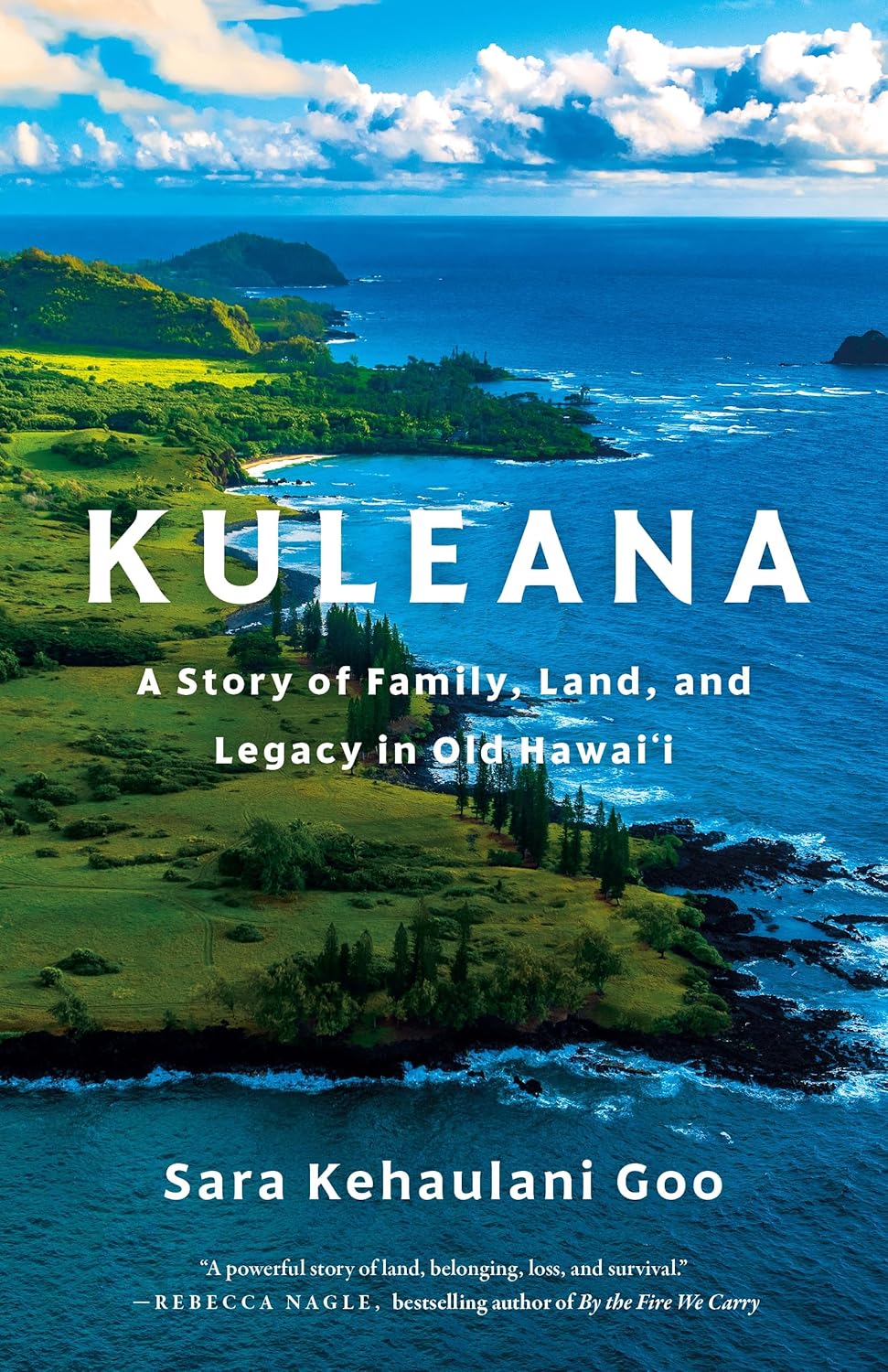

Kuleana: A Story of Family, Land, and Legacy in Old Hawai’i

- By Sara Kehaulani Goo

- Flatiron Books

- 368 pp.

- Reviewed by Rose Rankin

- July 7, 2025

The fight for an ancestral home unfolds amidst a history of dispossession.

When wildfires destroyed the city of Lahaina on Maui in 2023, it brought a number of issues to the public’s attention — ecological damage from plantation agriculture, for one, but also the dire lack of affordable housing for residents of Hawaii.

Land dispossession by wealthy outsiders — from plantation owners in the 19th century to tech moguls in the 21st — has driven up property prices and put home ownership (and rentals) out of reach for many residents, particularly native Hawaiians, for centuries. These problems weren’t on most Americans’ radar until the disaster in Lahaina, but for Indigenous families like Sara Kehaulani Goo’s, the tragedy was just the latest example of a slow-moving yet constant process to force residents off their land via exploitative economic practices.

It’s against this backdrop that Goo shares her family’s story of fighting tax reassessments, bureaucracy, and their own internal conflicts in an attempt to maintain their ancestral lands on Maui. Kuleana is at heart an autobiography of one family, but the book is at its best when Goo ties her experience to the larger history and economics of America’s paradise.

The daughter of an Indigenous Hawaiian/Chinese-American father, Goo begins her story by describing her upbringing as an Asian American in Southern California and her lifelong interest in understanding her roots. The Hawaiian side of her father’s family was given a large parcel of land in 1848 by King Kamehameha III, one of Hawaii’s last rulers. The land and the culture fascinated Goo her entire life and was the heritage she most identified with.

But, the realities of school, career, and raising her own family kept her far from Hawaii, both physically and spiritually. Goo is a successful journalist who’s had a front-row seat to history since the turn of the 21st century, and in the book, she also recounts her professional achievements at the Washington Post, living in Washington, DC, and the familiar grind of being a working parent.

All of this takes place very far from Maui, but woven into the narrative is the story of her family’s land being divided, sold off, and reduced to a fraction of its original size. In 2019, all of this is brought to a head when her father receives a property-tax increase of 500 percent on the remaining land, and Goo jumps into action to determine how they can keep what remains and not become one more Indigenous family forced to sell.

She does an excellent job exploring the history of dispossession, from the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy in 1893, to the appropriation of lands for sugar plantations, to huge purchases by the likes of Oprah Winfrey and Mark Zuckerberg in recent years. Goo shows that shady contracts, underhanded tactics, and pure greed aren’t shameful events from the past but a continuous, present-day problem in Hawaii and elsewhere.

When the concept of landownership was imposed on a society that had no history of possessing physical pieces of the earth, it opened the door for white colonists to take advantage of that society and game the system that they, the outsiders, knew so well. It all becomes very personal for Goo when the tax assessment threatens to take yet another slice of Indigenous land.

Goo applies her journalistic skills to better understand the legal and cultural history of her family’s gift from King Kamehameha III. Handwritten scraps of paper from the 1800s, lists of sales and leases, and even artifacts from the heiau, or temple, on her family’s land shed light on their story. Specifically, they show how plantation owners and outsiders carved up the original endowment. This knowledge motivates her to prevent any further losses, and she and her father commit themselves to navigating the bureaucracy (and their personal family dynamics) to find a way to reduce the tax bill.

Goo comes to see this task as her kuleana — her responsibility and privilege to care for her loved ones, community, and legacy.

The story then goes on a few side quests, such as when Goo and her children learn the traditional art of hula near their home in Virginia. The author’s reconnection with Hawaiian culture and her finding her sense of self are touching, but her hand-wringing over recalcitrant relatives and the many squabbles that accompany the land inheritance become a little tiresome. At times, she repeats anecdotes and gives the impression that even she has lost the plot amid all the twists and turns of filial tiffs.

Kuleana is, ultimately, a very human story of one woman and one family, but it’s most compelling when this family’s experience is placed in the larger context of colonialism and dispossession. It’s a reminder that the exploitation of native peoples isn’t consigned to history books, but neither are those peoples powerless to fight back.

Rose Rankin is a freelance writer from Chicago. She focuses on history, science, and gender issues, in particular women’s literary history.