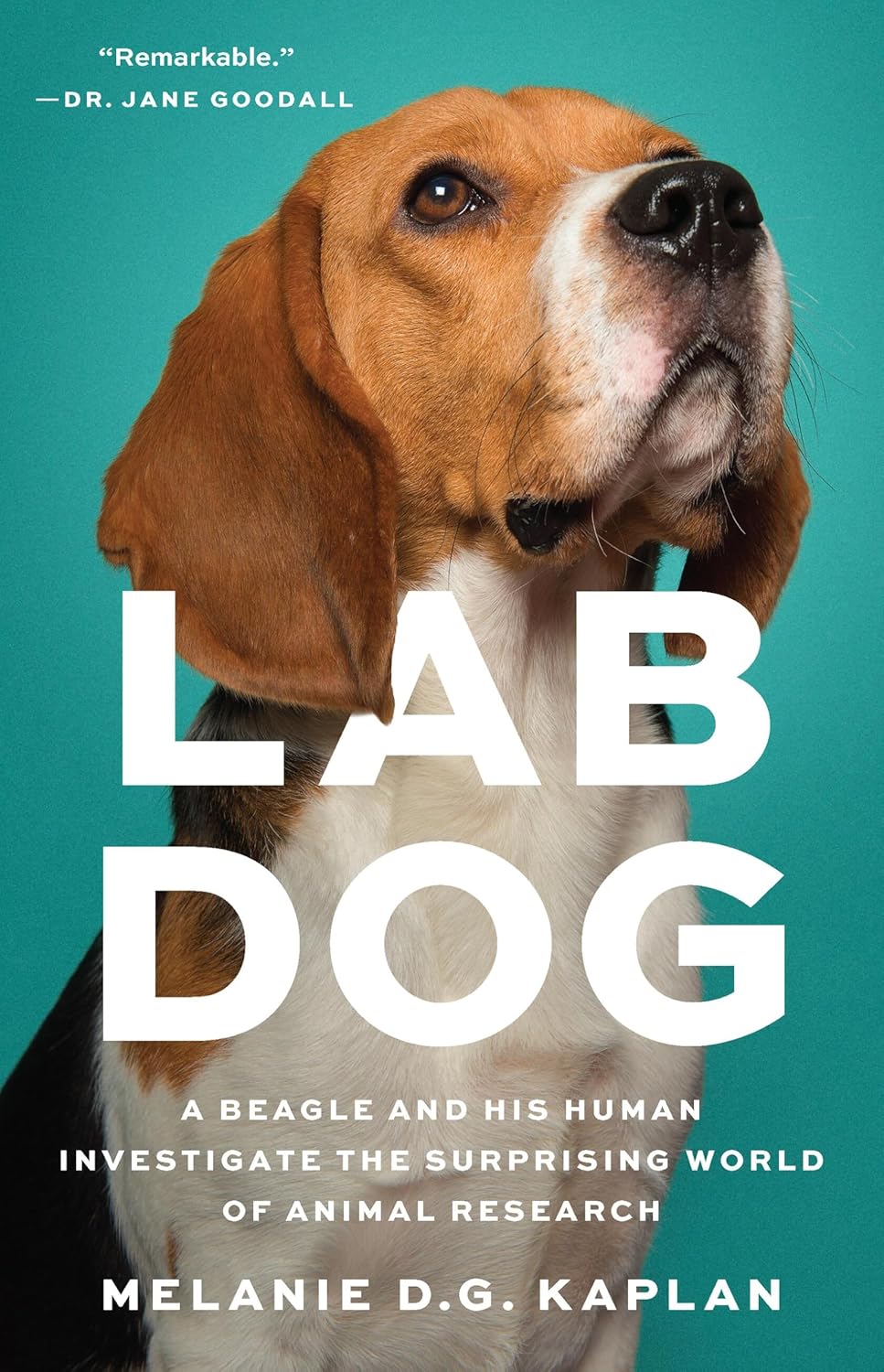

Lab Dog: A Beagle and His Human Investigate the Surprising World of Animal Research

- By Melanie D.G. Kaplan

- Seal Press

- 352 pp.

- Reviewed by Jay Hancock

- December 19, 2025

What are we doing to our four-legged brethren?

The Trump administration promises to reduce the torture of beagles, rabbits, monkeys, and mice in drug research as part of its “Make America Healthy Again” program. Federal officials talk about a “paradigm shift” of replacing animal tests with computer simulations and lab-grown organs. Fox News is in favor. The White Coat Waste Project, a Republican-linked animal-rights group, says the Trump people aren’t moving fast enough.

Changes favored by progressives often need conservative support before they become the rules of society. The animal-welfare movement of Albert Schweitzer and Jane Goodall has now signed up right-wing inflamer Laura Loomer. To understand how we got here, meet Hammy, freed from beagle prison and assigned to the lab beat alongside his human, journalist Melanie D.G. Kaplan.

To write Lab Dog, they drive around the country visiting breeding factories, universities, and rescue ranches. They interview scientists, business people, activists, and politicians. They politely query others making a living off of animal testing who never reply.

The project includes investigating the life of Hammy — who is sweet, anxious, and scared of cats — before Kaplan adopted him. Who bred him? What lab funded by FDA or NIH bought him? What did they do to him? Kaplan is honorably fair in a genre not known for balance, appropriately invoking philosopher Jeremy Bentham and the notion that a certain amount of harm can lead to immeasurable good.

Dog experiments were essential to the discovery of insulin. Manipulative brain surgery on monkeys and cats advanced neuroscience. Nasty procedures on dogs and pigs led to heart-disease treatments in people. Kaplan correctly notes that animal-welfare advocates sometimes seem more interested in publicity and fundraising than in helping animals.

Labs hesitate to offer post-test beagles for adoption instead of euthanizing them because activists take the pups and put them in panhandling and outrage videos. Rescue ranches quietly cooperating with labs get accused of giving cover to moral criminals. But even unsentimental utilitarians want to minimize harm in the pursuit of good. What jumps out from Kaplan’s book and recent news in Washington is the scale of animal tests and the wantonness and uselessness of most of them.

The industry casts suffering creatures as “heroes” helping humanity, but their sacrifices lead to appallingly few new treatments or scientific discoveries. The main purpose of animal testing seems to be maximizing employment for breeders, scientists, lab personnel, vice deans of research, and FDA and NIH program officers.

As much as 90 percent of candidate drugs that seem promising in animal experiments don’t work or are too dangerous for humans, physician and senior FDA advisor Tracy Beth Høeg said this summer at a workshop on reducing animal testing.

In any given year, there are some 50,000 dogs in labs across the country, animal-rights groups estimate, most of them beagles. And researchers use 111 million mice and rats a year, a recent Nature paper estimated.

“There’s a paranoia out there about the public seeing the numbers,” an animal-science administrator at Boston University tells Kaplan.

Cold War researchers injected beagle pups with plutonium, radium, and strontium, logging the resulting tumors, disfigurations, and deaths. The experiments left an EPA superfund site on one California campus filled with the radioactive remains of 800 dogs. Ivan Pavlov, the Nobel laureate remembered for his salivating dogs, tortured his animals.

Dogs evolved to be loving and loyal to humans. Sentencing them to lab row is “a horrible betrayal,” dog-cognition researcher Alexandra Horowitz tells Kaplan. A doctoral advisor told one junior scientist that her concerns about experimenting on animals made her “emotionally immature.”

Anguish over cruelty to animals goes back centuries. Kaplan might have mentioned that the utilitarian Bentham was also an early animal-rights advocate. The question is not whether animals can reason or talk, Bentham said, but “can they suffer?”

As long ago as 1876, the United Kingdom passed a Cruelty to Animals Act requiring licenses for animal experimentation. It was ineffective, Kaplan writes. The U.S. Animal Welfare Act has been updated eight times since its initial passage in the 1960s, but outrages continue. Just three years ago, state and federal authorities raided a beagle mill in Cumberland, Virginia, finding hundreds of dogs in “acute distress.”

The company paid millions in criminal fines and agreed to free thousands of dogs for adoption. Hammy and Kaplan were there to witness the liberation as vans and cars exited the chain-link stalag with beagles on board. Perhaps Hammy had a flashback.

Conservatives’ distress about cruelty to animals goes back at least to Matthew Scully, a speechwriter for George W. Bush, who, in 2002, published Dominion: The Power of Man, the Suffering of Animals, and the Call to Mercy. Scully was “an unexpected defender of the animals against the depredations of profit driven corporations,” the New York Times said in a review. Recently, right-leaning influencers realized they could amplify hatred of Anthony Fauci by adding NIH beagle abuse to their bill of complaint.

Kaplan is a nice writer who is generous about crediting sources in her book’s text. Much of what she covers should be familiar to people who follow the subject, but for those who don’t, Lab Dog is a discomfiting and timely dispatch as the animal-testing tide seems to be turning.

Jay Hancock was the chief economics correspondent for the Baltimore Sun. His free Substack newsletter is here.