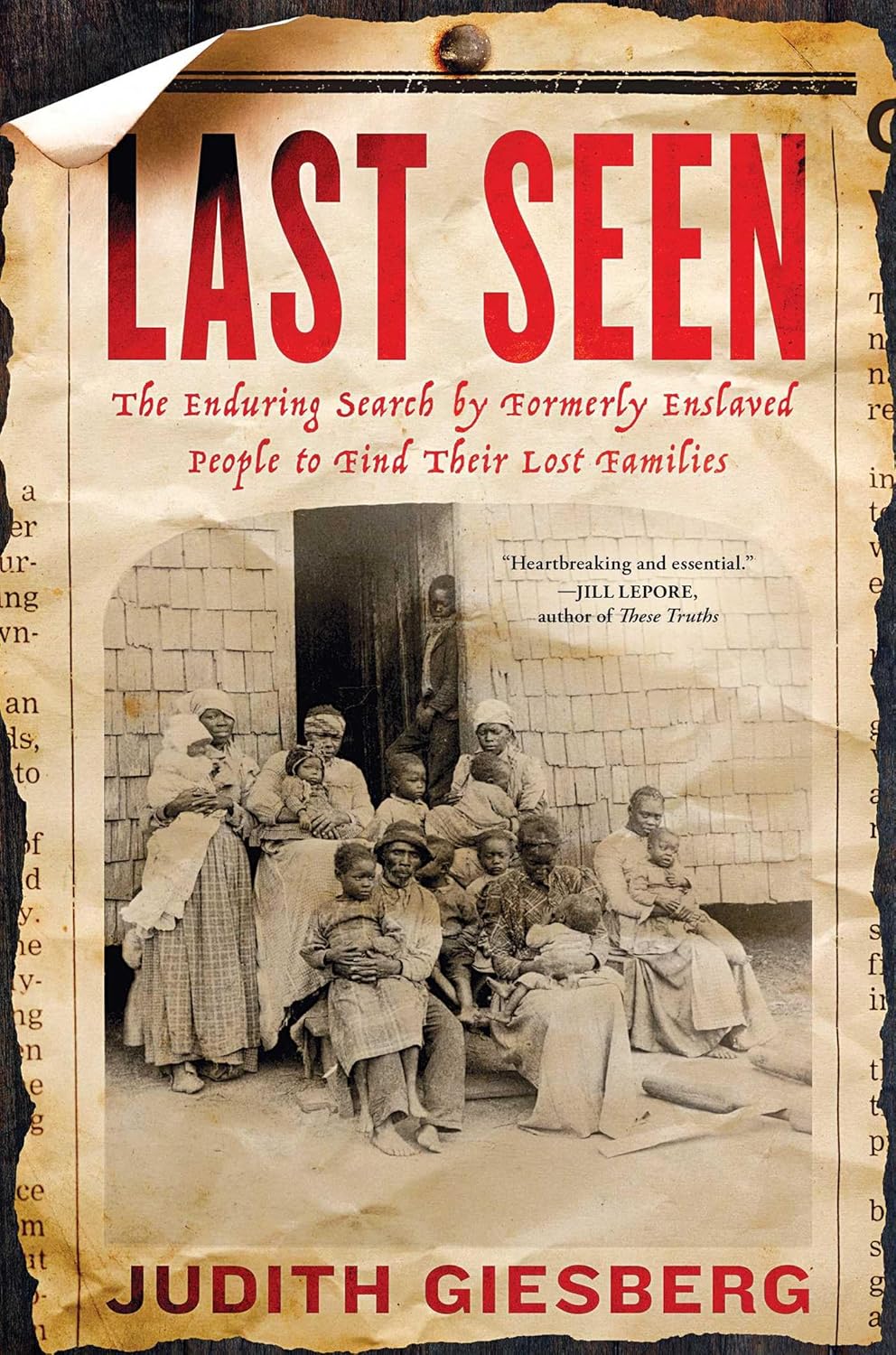

Last Seen: The Enduring Search by Formerly Enslaved People to Find Their Lost Families

- By Judith Giesberg

- Simon & Schuster

- 336 pp.

- Reviewed by Paula Tarnapol Whitacre

- February 24, 2025

Tragic accounts of seekers and the stolen.

Advertisements for runaway slaves were a well-known feature of newspapers before and even during the Civil War. As enslavers went on the hunt and offered rewards for capture, they inadvertently described the characteristics and tenacity of the people whom they considered their property.

This tenacity was also reflected in another set of notices that appeared in papers after the war. Lesser known today, they form the basis for Last Seen: The Enduring Search by Formerly Enslaved People to Find Their Lost Families by Villanova University historian Judith Giesberg. They make for heart-rending reading.

A few examples of the more than 4,500 notices that Giesberg and her colleagues have collected in their publicly available “Last Seen: Finding Family after Slavery” database:

From Diana Johnson of Goliad, Texas: “Mr. Editor — I desire to find the whereabouts of my mother, sisters, and brothers, whom I left in Roan [sic] County, North Carolina.”

From Tally Miller of Shreveport, Louisiana: “Mr. Editor — I wish to inquire through your paper for my two children that I left near Chester Village, Chester County, South Carolina, about 1837.”

From a man living in Sacramento, California, in 1869: “John Walker, a servant of Dr. E.M. Patterson in 1856, wishes to know the whereabouts of his wife Peggy, and his three sons, William, Samuel, and Miles, who were also slaves of Dr. E.M. Patterson.”

These writers, of course, did not choose the fact that they “left” relatives behind. As Giesberg notes in her excellent introduction, “By 1860, one million enslaved people had been sold from the Upper South to the Deep South. Each of them left behind family. One quarter of those sold were between the ages of eight and fifteen.” This movement of people, known as the domestic slave trade, occurred within the United States (in comparison to the forced trans-Atlantic passage of people from Africa to the Americas).

The chapters begin with a reprint of an original notice or article, followed by as much information as could be mined through wills, census records, and other documents. Giesberg selected the dozen or so notices because of their relative abundance of information or because they reflect a common theme (such as the search for husbands and wives). A certain amount of conjecture takes place. Words like “surely” and “may have” show up often in the text.

Giesberg notes that the most frequent question she receives on her website is about whether the seekers featured in her database ever connected with those they sought. Sadly, most did not. Reunions, she emphasizes, were the exception. Of the 4,568 advertisements in the database, there were only 105 known resolutions, or two percent. Families torn apart via the domestic slave trade unfortunately remained apart.

Many reasons account for the lack of resolution. Too much time had transpired (in some cases, decades). Too few details could be provided, especially among people given no identifying documents of their own. Distances between people with extremely limited resources spanned hundreds, even thousands, of miles. Those being sought might not have seen or heard about the notice or, in some cases, chose not to respond. And, of course, everything happened in an era without computers, social media, TV, or even radio.

In fact, not only were reunions rare, but Giesberg points out that publicizing them fed a narrative that romanticized and trivialized the trauma of separation. For mainstream (i.e., white-controlled) newspapers, “these feel-good vignettes” or “slavery stories with happy endings” depicted a very different story than the reality. For example, an article in a Chicago newspaper noted that when two sisters reconnected, “the reminiscences of slavery days…are of the most interesting nature.” Another tack was to dramatize the saga to sell papers. An article in the New York World subsequently carried by papers across the country was headlined “Thirty Years Search: Mrs. Bashop’s Pitiful Search for Her Daughter, Patience.” Giesberg tells fuller stories of these women’s situations in Last Seen.

The entry point for each chapter is the individual, but the stories serve to tell the broader context of what was happening at the time of the separation and/or when the notice appeared. Tally Miller’s story, for instance, provides a way to discuss the economics of the cotton trade. We learn about Texas as the far reach of the slave structure through the stories of Diana Johnson and a family called the Andersons. The role of the U.S. Colored Troops is discussed in chapters about men who escaped slavery, enlisted, and applied for pensions after the war. And the importance of the Black press and Black churches as trusted sources of information is shown throughout the book.

Because I live and write about Alexandria, Virginia, I began Last Seen curious to see whether the city’s notorious slave-trading businesses would appear in any of the notices. It didn’t take long. Chapter four revolves around a notice placed by Henry Tibbs, age 55, in 1879: “I desire some information about my mother. The last time I saw her was in Alexandria, Virginia, about the year 1852 or 1853.”

His rendering of names and dates was hazy, according to the follow-up research, but one clear detail remained with him for decades: “She brought me some cake and candy and that was the last time I saw her.” Tibbs ended up in the Mississippi Delta through a series of “swaps,” a child without his mother whose survival depended on “networks of communication, worship, and support that existed beyond the detection of enslavers.”

In Last Seen, Judith Giesberg provides a powerful way to understand the crime of slavery and, just as importantly, the enduring strength and faith of families.

Paula Tarnapol Whitacre writes about history, with a focus on 19th-century social history. She is currently working on a book about the Civil War and Reconstruction focused on Alexandria, Virginia, under contract with Georgetown University Press.