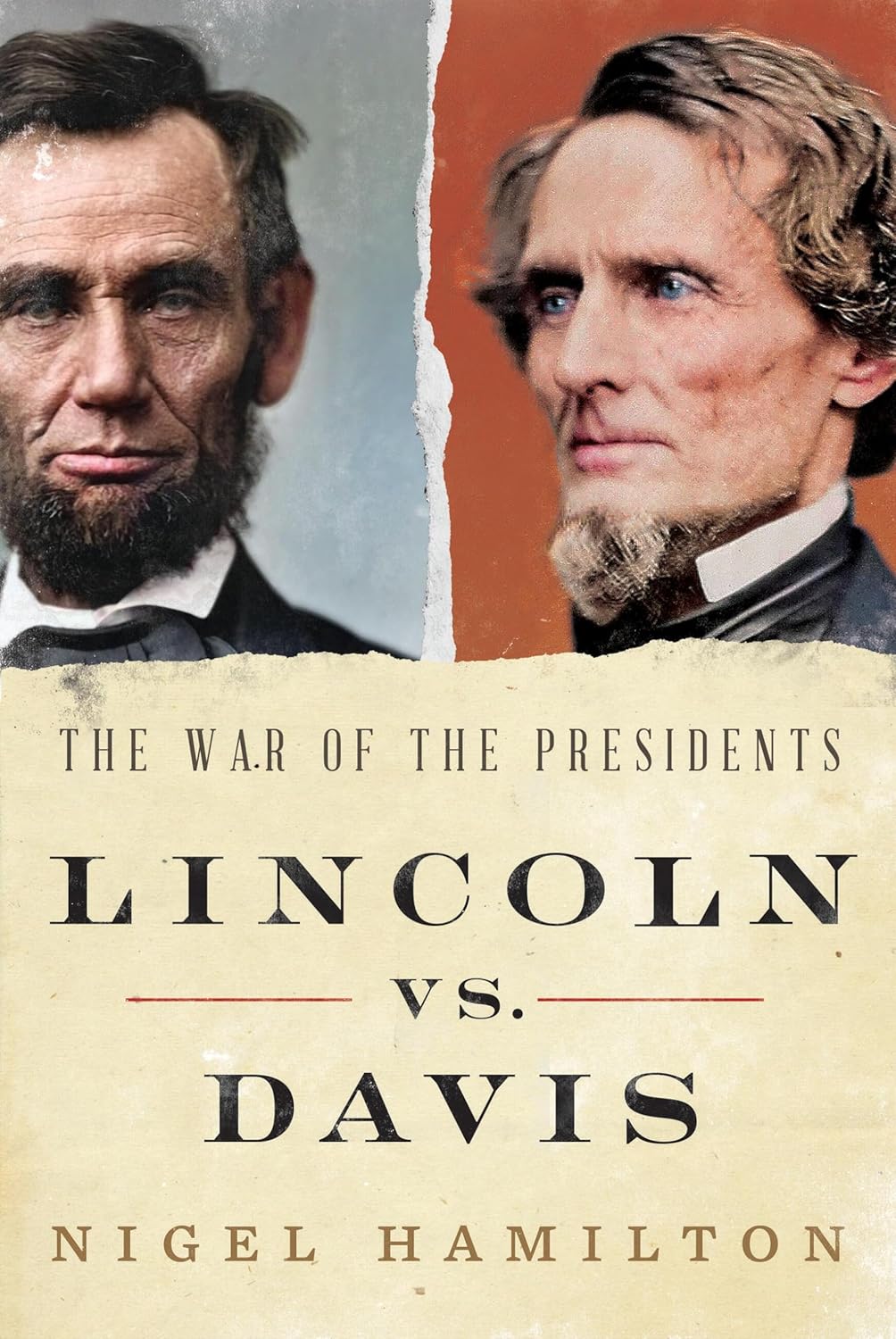

Lincoln vs. Davis: The War of the Presidents

- By Nigel Hamilton

- Little, Brown and Company

- 800 pp.

- Reviewed by Andrew M. Mayer

- November 5, 2024

This outstanding double biography brings the dueling leaders vividly to life.

Nigel Hamilton, the author of multiple books and a senior fellow at UMass Boston’s McCormack Graduate School of Policy and Global Studies, has written in Lincoln vs. Davis a sterling dual biography of the competing presidents during the U.S. Civil War: Abraham Lincoln, the 16th commander-in-chief of the United States of America, and Jefferson Davis, the first and only commander-in-chief of the Confederate States of America.

What is unique in Hamilton’s approach to covering the two men is that he uses a seminal event during the period — the issuing of the Emancipation Proclamation — as a throughline. He begins his narrative with Lincoln’s and Davis’ inaugurations (on March 4, 1861, and February 11, 1861, respectively), occurrences that themselves were fraught. “Whether either of the two presidents-elect would even reach his appointed destination was questionable as they left their homes in Illinois and Mississippi, given the partisanship, secession, and dissension riving the country since Mr. Lincoln’s election on November 6, 1860,” Hamilton writes.

“Assassination had been threatened against both men in their roles as standard-bearers of their sections of the country: ‘Black’ Republicans (so called because their party opposed slavery) versus Southern Democrats (who were intent upon preserving slavery if not forever, then for as long as possible).”

Lincoln had eked out his win after a contentious four-way race; in the months between the election and his inauguration, his predecessor, Democrat James Buchanan, stood by as seven Southern states — Alabama, South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas — seceded from the Union. Barely a month after Lincoln’s swearing-in, Confederate troops fired on South Carolina’s Fort Sumter, sparking the Civil War and precipitating the secession of Virginia, Arkansas, North Carolina, and Tennessee.

As chief executive, Lincoln faced more initial difficulties than Davis, including being surrounded by a cabinet that sometimes kept him in the dark. His secretary of state and onetime rival, William H. Seward, for example, quietly sought to abandon Fort Sumter to the Rebels and thus avoid war. Incredibly, Lincoln was filled in only belatedly. The author effectively uses this and other incidents to illustrate how the men around Lincoln initially saw him as little more than a figurehead they could manipulate.

They knew Lincoln, unlike Davis, had scant military experience and used it against him. Lincoln was further foiled by his own leader of the Union Army, General George B. McClellan, who consistently underplayed the size of Union forces and overplayed that of Confederate forces in delaying action for several months. Catastrophic defeats at both Battles of Bull Run, in the Peninsula Campaign, and elsewhere eventually prompted Lincoln to sack McClellan in favor of a series of other generals. Ultimately, he would name Ulysses S. Grant leader of the North’s entire fighting force.

Davis, for his part, had been an officer in the Mexican-American War — “Mexico, almost inevitably, had been the making of Jefferson Davis,” writes Hamilton — and actually led Confederate forces in the Bull Run battles (known in the South as First and Second Manassas). Realizing by 1862 that he was losing ground to Grant in the West, Davis was persuaded by Robert E. Lee to take the fight to the North in Sharpsburg, Maryland, in hopes of stoking fellow feeling among sympathetic Yankees, forcing a peace with Lincoln, and preserving the institution of slavery. The resulting clash on September 17, 1862, would prove to be the single bloodiest day in American history. While devastating for both sides, the Battle of Antietam was seen as a Union victory, and it closed the door on the Confederacy’s efforts to establish European markets for its exports, striking a blow to the future of “King Cotton.”

Antietam also prompted Lincoln to play his trump card: On September 22, 1862, just days after the battle, he issued a preliminary proclamation. It stated that if the South did not end its rebellion within 100 days, every slave held there would be declared free. When he followed through on his pledge on January 1, 1863, with the Emancipation Proclamation, it was as if a bomb had gone off in the South, and even in parts of the North. Lincoln faced opposition in his cabinet and throughout the Union. But Lee’s bold initiative to spark a Northern uprising had spurred Lincoln to undertake bold initiatives of his own.

What is not covered in the book is the growing desperation felt by the Confederacy after the proclamation forced Davis and Lee to make increasingly aggressive (and increasingly unsuccessful) battlefield decisions in places like Vicksburg and Gettysburg. It all came to an end on April 9, 1865, when Lee formally surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Courthouse in Virginia.

Lincoln, 56, was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, DC, five days later. Davis, who’d fled the Confederacy’s Richmond capital at the beginning of April, was arrested the next month in Georgia and served several years in federal prison. After his release, he wrote occasional columns and a memoir, dying in 1889 at age 81.

Hamilton distinguishes his work by focusing on the pivotal impact of the Emancipation Proclamation on the war and on the men leading it. “In some ways, the two Americans were remarkably similar,” he writes. Lincoln and Davis “were almost exactly the same age, born in Kentucky…little more than 100 miles apart. Both men had been U.S. congressmen in the 1840s…Both had already lost a son and would lose one more in the following struggle. Both were tall and imposing.” Time would reveal, of course, that in other ways, Abraham Lincoln and Jefferson Davis were very, very different.

Andrew M. Mayer is professor emeritus of humanities and history at the College of Staten Island/CUNY.