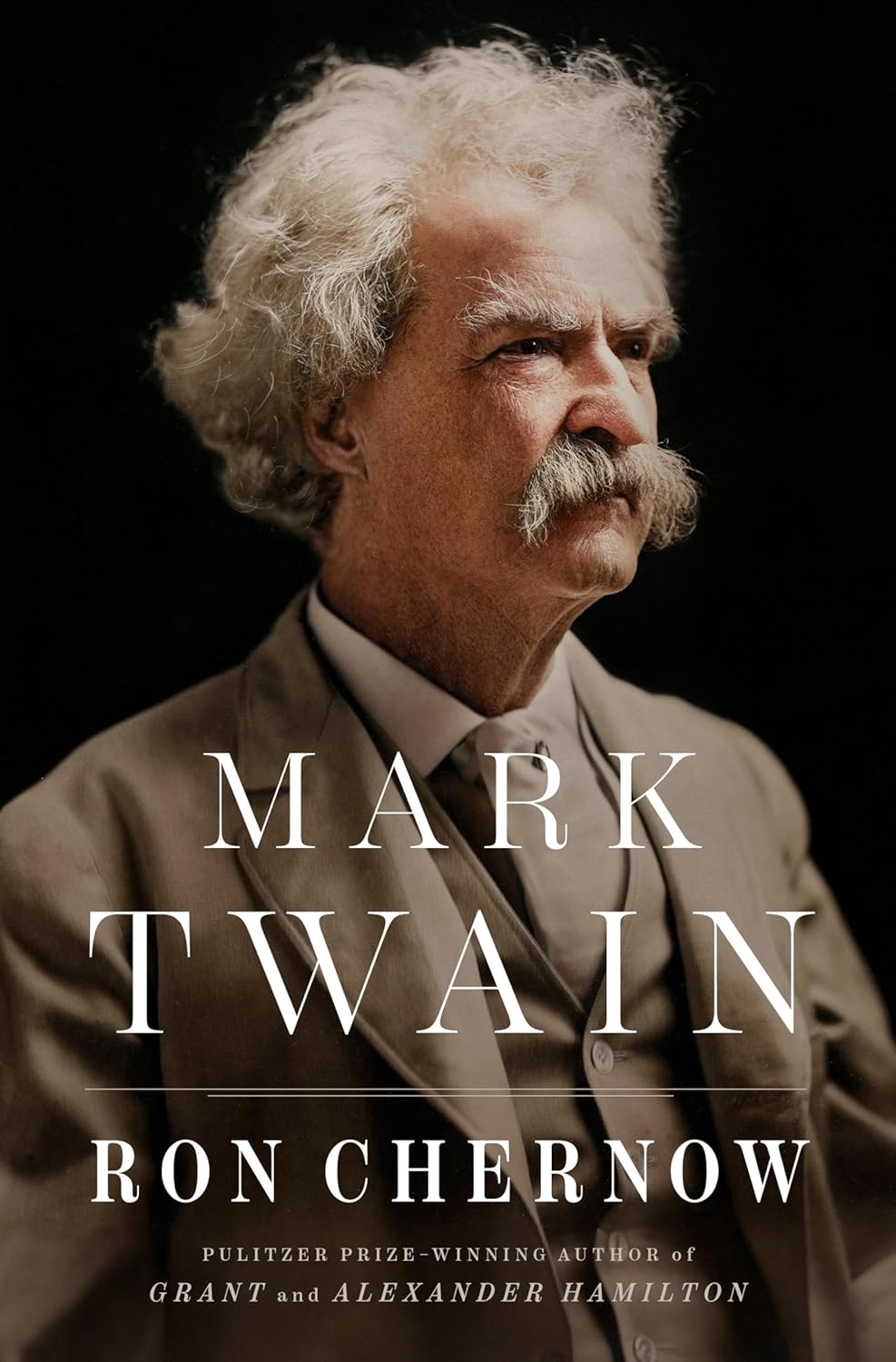

Mark Twain

- By Ron Chernow

- Penguin Press

- 1,200 pp.

- Reviewed by Karl Straub

- May 12, 2025

This stellar biography doesn’t shy away from revealing its subject’s darker side.

For the modern-day reader eager to face the egregious errors of history while still enjoying the literary legacy of our pedestaled ancestors, Mark Twain presents a battle that isn’t merely uphill but uphill in lousy weather.

Ron Chernow’s Mark Twain arrives during this difficult season for long-dead writers, and it’s hard to imagine a biography proving more useful to Twain lovers and bashers alike. In examining the art and life of a man both adored and reviled, Chernow has presented the case without romanticizing or (it must be said) bowdlerizing his subject. If Twain were alive to read this book, or to lift it, he might wonder aloud how many people would actually survive the trip from one cover to the other.

It took a Mississippi River’s worth of pages for Chernow to bring us this thorough look at a life filled with many triumphs but also numerous body blows — most of them self-inflicted — without causing us to forget how much fun Twain can be to read. Readers of Chernow’s book will slog through many unpleasant periods in Twain’s life, only to suddenly round a corner and hear about another of the man’s great works, many of which were overshadowed by his more famous books.

Even Twain’s less-familiar catalog is an embarrassment of riches, and Chernow is a capable curator both of the writing and the peccadilloes. Those inclined to skip over painful passages about Twain’s life to get to Chernow’s reading recommendations may miss some valuable insights, but they’ll indeed still profit. Normally, when reading Twain, it takes some digging to get past Huck and Jim and Tom to discover bitter satire like The Man Who Corrupted Hadleyburg and The War Prayer (not to mention Twain’s many short comic pieces), but Chernow has done the excavating for us.

He has also unearthed a considerable amount of forgotten witty remarks. On an international cruise, for instance, Twain was subjected to the society of a businessman who wrote egregious doggerel, printed it up, and forced it upon fellow passengers with great regularity. Twain dubbed this man “the Poet Lariat.”

Chernow contradicts the bucolic tone of Twain’s fictionalized version of his youth, while shedding light on how Samuel Clemens became the writer we know. Tragedies surface uncomfortably amid all the early fun; among them, the untimely death of his brother and Twain’s feelings of guilt about it, his father’s decline, and the various seeds of the author’s later distance from his family. Chernow helps us see how, and why, Twain let darkness creep into his work, but he also shows that Twain’s comic instincts never deserted him, even as death and loss preoccupied him.

Twain was “a born salesman, with a glandular optimism,” Chernow writes. This is an apt characterization of Twain’s proselytizing for questionable enterprises but also of his selling of himself as a mythical figure. He was one of the first celebrities to achieve fame in this way, and the story of how he created and successfully marketed his own legend is well told here.

Chernow also gives us convincing evidence that one part of the Twain myth wasn’t what Huck Finn would’ve called a “stretcher”; while Twain whitewashed much of his own thoughtless behavior, and was very good at blaming others for the mistakes he couldn’t manage to deny, he did not exaggerate his own comic abilities. (Not that he didn’t try.)

“Never a tepid convert to any cause,” Chernow observes, writing about the epilepsy of Twain’s daughter Jean, “Twain blithely assumed the Kellgren treatment was a cure-all for almost any conceivable illness.”

Setbacks often forced the credulous and myopic Twains to rethink plans, and this is a common refrain in the book. After one disappointment, Chernow tells us, “the footloose family, weighed down by eight trunks of luggage, was condemned to wander the earth for another season.”

In an example of the unwelcome but necessary task for Twain scholars to cover the darkening of the man’s writing in the wake of an acre of emotional trials and personal losses, Chernow ably reports:

“During his Viennese period, Twain’s adages more and more shifted from pure laugh lines to sardonic reflections on the human condition, some so freighted with dark meanings as to stop us cold in our tracks.”

Chernow illustrates the point here, when Twain turns his style of witty understatement inside out. “Unfortunately none of us can see far ahead; prophecy is not for us,” Twain wrote. “Hence the paucity of suicides.”

The man lives on in the pages of Mark Twain, his contradictions intact, and Chernow brings him to life with empathy but not indulgence. It’s the book Twain deserves and also the book deserved by both his fans and his detractors. Twain would surely wrestle over which group deserves it most.

Karl Straub studied music education at Howard University and writes about music, books, film, and TV at karlstraub.substack.com. He lives in Alexandria, Virginia.