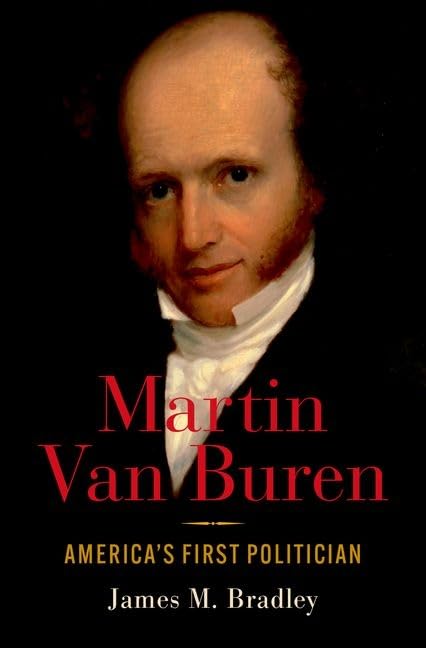

Martin Van Buren: America’s First Politician

- By James M. Bradley

- Oxford University Press

- 632 pp.

- Reviewed by Eugene L. Meyer

- December 10, 2024

Forget everything you thought you knew about our eighth president.

The subtitle of Martin Van Buren: America’s First Politician, a deeply researched and well-written biography of our eighth president, might sound grandiose. But then, how else to promote a book about a middling, largely forgotten antebellum figure whose grave in tiny Kinderhook, New York, may be the least visited of all the presidential resting places?

Van Buren, whom author James M. Bradley and other historians credit with establishing the political-party system in America, is also distinguished by being the first commander-in-chief born in the new country (in 1782) and the only one whose first language was not English. Dutch was the lingua franca in the Van Buren household in the upper Hudson Valley village. He was not the only president of Dutch descent, however, and he was far from the most distinguished. That honor would go to Franklin Delano Roosevelt, of patrician patroon lineage, elected a century later.

If FDR faced strong headwinds in the Great Depression and then in the coming Second World War, Van Buren struggled through the economic Panic of 1837 and grappled, not very successfully, with the North-South schism that would eventually devolve into the American Civil War.

What makes this biography by Bradley, co-editor of the Papers of Martin Van Buren at Cumberland University, well worth plowing through more than 600 pages of text, notes, and indices is the context as much as the leading man. So much of consequence happened during Van Buren’s time as Andrew Jackson’s secretary of state and vice president, during his one four-year term as president, and finally in his unsuccessful campaign to return to office, first as a Democrat and then as a Free Soil candidate. The reader is amply rewarded with important history normally overshadowed by the populist Jackson at one end and the sainted Abraham Lincoln at the other.

In between, Van Buren resisted pressure to accept the Texas Republic into the Union because he opposed the expansion of slavery (but did not advocate its abolition and once even owned a slave identified as “Tom,” who escaped to Worcester, Massachusetts, in 1814). On the northern border, he rebuffed rogue efforts to annex Canada, a “filibuster” attempt that came close to starting a war.

As Jackson’s vice president, Van Buren was a natural successor. But he suffered as much as he benefited from inheriting the office from the controversial Jackson. Van Buren took office just as the Panic of 1837 was beginning and was blamed for it and the major depression that followed. His reliance on Jackson’s deflationary policies seemingly made it worse.

He faithfully fulfilled Jackson’s program to expel five Indian tribes from their Southeastern homelands. He even celebrated implementing this “Trail of Tears,” reporting to Congress in 1838 that it gave him “sincere pleasure to be able to apprise you of the entire removal of the Cherokee Nation to their new homes west of the Mississippi.” The removals had met without “any apparent reluctance” and “have had the happiest effects.”

For Van Buren, the presidency was a mixed blessing. It was not a job he loved; he once remarked that his two happiest days in office were his first and last. Defeated for re-election, he undertook to write a presidential memoir, not then a commonly employed retrospective by former chief executives.

Of the autobiography, Bradley writes, “Rarely has a book been so bad, yet so valuable…It reads like a parody of bad writing.” Still, “No student of antebellum US politics can ignore the book,” which ends abruptly in 1834, due to the author’s devotion to a sick son, Martin Van Buren Jr., who suffered from chronic and ultimately fatal asthma.

When the former president died in 1862, the New York Times obituary was especially harsh, asserting that Van Buren “has associated his name with no measure that which entitles him to the permanent gratitude of our people…he did nothing distinguishable to advance the cause of humanity and civilization.”

But Bradley defends his subject as “a man of his times” who made each decision “based on what he thought was right at the time.” He adds, “No American did more to create his nation’s party system.” Van Buren had seen the presidency decided twice by the House of Representatives rather than by the voters. This, he declared in 1835, was “one of the greatest evils,” which could be rectified only by stable and enduring political parties. That his Democratic Party would deeply split during the Civil War, nominating a “peace” candidate, offered little to support his sunny view.

“In the name of building a party and winning elections,” Bradley writes, “he perpetuated slavery and carried out Indian removal, two policies that strengthened southern power and brought the nation closer to war…This is not a ‘presentist’ critique; Van Buren’s contemporaries said the same thing.”

Bradley notes that the increasing role of money has distorted the system Van Buren so venerated. Yet, for all its flaws, he argues, the party system “has insured the success and durability of bourgeois democracy — current threats notwithstanding.” This is a huge caveat that further undermines Van Buren’s political legacy and the author’s sympathetic view.

The Founders get the most attention, but “the political system that Americans live under today is the realization of Martin Van Buren’s vision, not theirs,” Bradley writes. One is left to wonder, in light of present events, if his optimistic vision still pertains.

Eugene L. Meyer, a member of the board of the Independent, is a journalist and author of, among other books, Five for Freedom: The African American Soldiers in John Brown’s Army and Hidden Maryland: In Search of America in Miniature. Meyer has been featured in the Biographers International Organization’s podcast series.