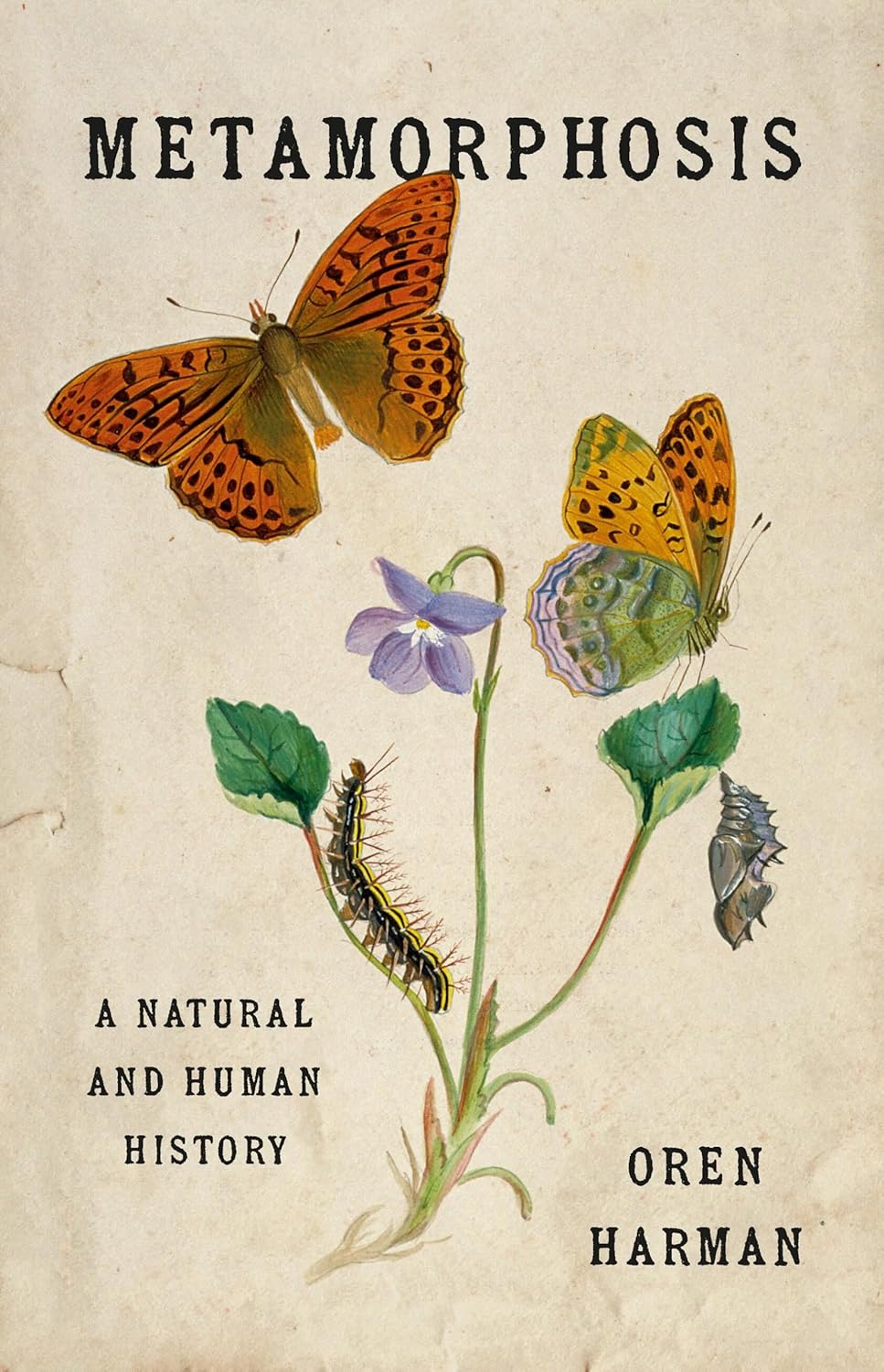

Metamorphosis: A Natural and Human History

- By Oren Harman

- Basic Books

- 400 pp.

- Reviewed by Julie Dunlap

- December 2, 2025

A startling exploration of the meaning of transformation.

In a lush, steamy land of passionfruit and pit vipers, Maria Sibylla Merian was perhaps the most exotic life form of all: a published artist, a scientist, and an independent woman. In 1699, she had left hearth and ex-husband in Amsterdam in search of tropical insects. In Surinam’s rainforests, she sought pieces to a puzzle no less than how biological order arises in a chaotic universe. Evidence Merian needed crawled and buzzed and flapped all around her.

Yet perhaps the most evocative clues seemed to rest in quintessential stillness. Suspended from twigs on slim pads of silk, butterfly chrysalises belied the tenacious belief that “lesser” organisms burst fully formed from mud or rotting meat. Once she re-crossed the Atlantic, crates of meticulously collected eggs, larva, pupa, and adult insect specimens would help her dismantle the myth of spontaneous generation. “In a world struggling to come to terms with the place of Man — and Woman — in God’s universe,” writes author Oren Harman, “Merian’s life is a performance of the period’s emblematic question: Where do we come from?”

Harman presents Merian’s 1705 Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium as a landmark in a scientific odyssey that began with Aristotle, who favored observation to discern reality over reasoning toward changeless Platonic Forms. Harman, a renowned historian of science and the author of Evolutions and The Price of Altruism, is adept at describing the interplay of facts and ideas that have shaped the dynamic field of evolutionary biology. In Metamorphosis: A Natural and Human History, he focuses on one biological process — physical change from conception to maturity — to challenge our understanding of life’s beginnings, middles, and ends. Centered in wonder, this creative and stimulating work reveals the quotidian and the magical about scientific discovery, always circling back to the meanings of these findings for our understanding of self. “Humans are story-telling creatures,” he explains, and stories, like cell birth and death in embryonic brains, transform our very beings.

Critics of Harman’s recursive style (which he dubs “a spirit of loose-jointedness”) will appreciate at least that he starts with a clear definition of biological metamorphosis: “radical post-embryonic development.” But in that same paragraph, and on almost every page, the book rejects a narrow view of a phenomenon we learn from a parent reading The Very Hungry Caterpillar. “We may not molt, or grow wings,” the author insists, “but considering our transformations into sexual adulthood, we too undergo dramatic change.”

Deep, often twisting dives into history illuminate old fallacies like spontaneous generation. Aristotle, despite seeing insects mate, refused to believe creatures low on his scala naturae could even have parents. For humans and other more perfect creatures, however, he held that male seed carries the form and cause of a new individual. Females contribute only menstrual blood; as the embryo grows, the seed shapes the blood-matter like a sculptor molds clay. Of course, wrote Aristotle, the sculptor is more perfect than the clay.

Harman credits a 17th-century Danish anatomist’s prolific dissections of dogs, sheep, birds, deer, and sharks with a key breakthrough. Nicolas Steno determined that structures then called female testicles were, in fact, ovaries; all female organisms, including those that have live young, produce eggs. Still ranking males above females on religious grounds, Steno could not deny his own discoveries. That revelation sparked a race among Maria Merian’s contemporaries to delineate relative male and female contributions to embryogenesis. Harman’s rich and lively tales of that era, a two-century war between “spermists” and “ovists,” are among the book’s most riveting passages.

In the 19th century, evolutionary theory would catalyze new ways of interrogating biological mysteries. “No longer perfect creatures, finished by the hand of God,” writes Harman, “species were now seen to be in a state of constant flux.” In one of several charming natural-history chapters, he uses poetry, colonial history, and Peter Pan to dramatize 1870s efforts to apprehend metamorphosis in axolotls. The now-familiar, whimsical-faced amphibian once stymied herpetologists by retaining its gills, undeveloped gonads, and other tadpole-like traits in adulthood. Yet, in the laboratory, these larva-like salamanders could reproduce. Says Harman:

“Of all the creatures evolution has divined, this one may be the weirdest.”

Experiments eventually showed that axolotls could be induced to express a mature terrestrial form, but Harman highlights a greater change that emerged in the understanding of evolution. Victorian Social Darwinists were disturbed by the animals’ so-called arrested, even regressive, development. It threatened their conviction that, just as natural selection drives biological advancement, “survival of the fittest” among humans powers social progress. That relentless progress, they claimed, justified imperialism, laissez-faire capitalism, racism, and eugenics. Passages on the abuse of scientific methods in service of biological determinism recall Stephen Jay Gould’s classic The Mismeasure of Man and are among Harman’s most chilling.

Axolotls — and modern genetics — helped jettison ideas of evolution propelling creatures up the Great Chain of Being and relegated Social Darwinism to pseudoscience. As Harman puts it, “in the lottery of genetic mutations, whatever worked best was what survived.”

The book also traces a more personal metamorphosis: the development of Harman’s third child from a “microscopic speck” in a watery womb to a blinking, smiling, air-breathing infant. Interspersed with chapters on starfish, the “symphony” of DNA regulation, and Neo-Darwinian theory, the author ruminates on the miraculous process of his daughter’s multiplying neurons and his family’s transition to an entity of five. Baby Sol’s very existence poses a new set of conundrums: “What is an individual?” “Why must we struggle to change?” And how is it possible that “we remain the same while changing all the while?”

Metamorphosis is steeped in wonderment, equal parts history of science, collective biography, and “meditation of a father-to-be.” It is also hauntingly timely; today, the work of empiricists like Maria Sibylla Merian is again threatened by ideology. Our very planet is transforming, and knowledge un-freighted with dogma is more essential than ever. With Harman’s expansive definition of radical change, here is the most penetrating question he raises: What kind of beings do we want to become? This probing book is for anyone who appreciates the splendor of the scientific enterprise and especially for anyone who doesn’t.

Julie Dunlap writes and teaches about wildlife ecology, environmental history, and climate change. Her children’s books include I Begin with Spring: The Life and Seasons of Henry David Thoreau, Tilbury House, 2022).