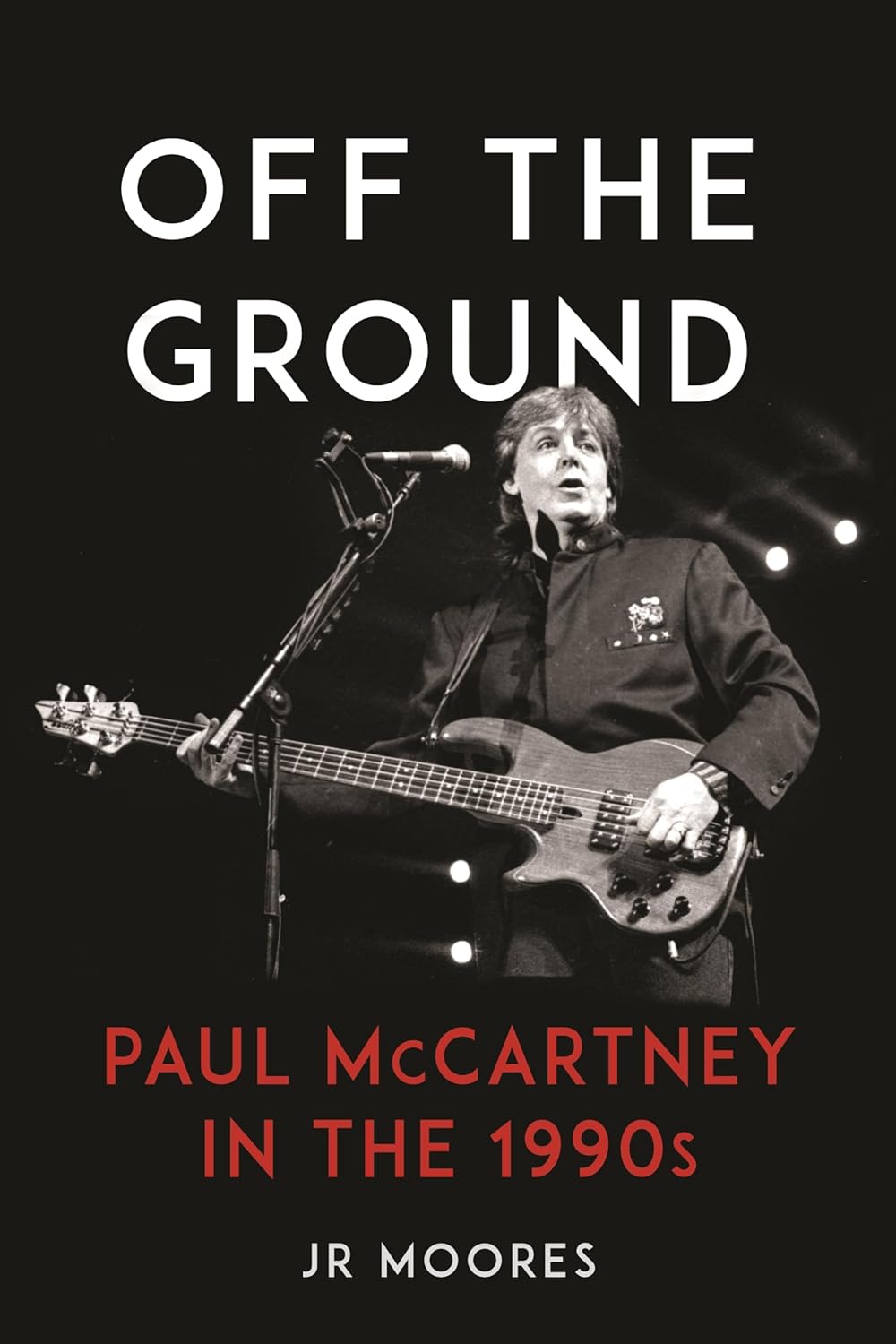

Off the Ground: Paul McCartney in the 1990s

- By JR Moores

- Reaktion Books

- 320 pp.

- Reviewed by Randy Cepuch

- January 17, 2025

An unfocused look at an important decade in the life of the cute Beatle.

Sometimes, it seems there are nearly as many books about the Beatles, collectively and individually, as there are holes in Blackburn, Lancashire (4,000, per the lyrics of “A Day in the Life”). It’s probably not as many as have been written about Abraham Lincoln, but his heyday preceded theirs by a century.

While it’s inevitable that there’s more recycling of material over time, several books in recent years have genuinely added to the Beatles canon. In 2023, for instance, Kenneth Womack gave us Living the Beatles’ Legend: The Untold Story of Mal Evans, a superb biography of the band’s indispensable and omnipresent assistant.

Digging deeper than earlier authors to produce exhaustive (and sometimes exhausting) voluminous minute-by-minute tick-tocks like Mark Lewisohn’s Tune In: The Beatles: All These Years and Allan Kozinn and Adrian Sinclair’s The McCartney Legacy has also shed new light. (Notably, the abridged version of the former runs 944 pages, and the extended edition is 1,728 pages, and that’s just volume one, with two more expected to follow. Similarly, volume one of the latter is 720 pages, while volume two is 768 pages and ends in 1980!)

In Off the Ground: Paul McCartney in the 1990s, JR Moores attempts to focus on a single decade in the former Beatle’s life. “As we shall see, Paul McCartney’s 1990s were an era like no other,” he writes. “It could even be argued that this was the most significant decade of his entire career after the 1960s.”

That’s the premise of this work, whose title comes from a 1993 McCartney album and whose subhead specifies the decade to be examined. Unfortunately, it doesn’t quite do what it says on the tin. Too often, the focus is blurry.

Page after page is filled with detailed recollections and criticisms of Britpop, Cool Britannia, U.K. politics, and even the comedy of Jerry Seinfeld, eventually circling back to offer occasional brief interjections — “Meanwhile, Paul McCartney…” — and other attempts to tie things together. There are more than a few quibbles with other journalists and authors, apparently included to discredit them or settle scores, several of which have little to do with the subject at hand. (Writing this, I realized that I’m a reviewer reviewing a reviewer reviewing reviewers. Yikes.)

A lengthy first chapter details things that happened before 1990: lauding Beatle achievements such as “composing pop music that sounded like nothing before it, and growing startling moustaches,” considering how punk musicians did or didn’t embrace the Beatles, ruminating on reactions to the murder of John Lennon, and knocking Paul’s 1984 film, “Give My Regards to Broad Street.”

It’s completely understandable, of course, that Beatle references continue throughout the book. After all, in 1995, fans savored “The Beatles Anthology” television documentary, which featured two partial Lennon songs (“Free as a Bird” and “Real Love”) newly finished by McCartney, George Harrison, and Ringo Starr by pretending Lennon had simply stepped out for tea.

Still, some mentions of McCartney’s old bandmates on their own seem unnecessary and mean-spirited: Moores calls one chart-topping 1987 solo record by another ex-Beatle “duller than a bucket of unseasoned soup.”

Setting up the story of how McCartney was a Nirvana fan who eventually became close friends with Dave Grohl (that band’s drummer and subsequently the frontman for Foo Fighters), the author considers what Kurt Cobain and Lennon had in common:

“Both...came from broken homes. Each was tormented by his own celebrity status. They struggled with hard-drug abuse. They met tragic and violent ends, one self-inflicted; the other at the hands of a mad fan. They were fathers who left young children behind. People have scapegoated both men’s wives.”

It’s an interesting analysis, but perhaps better suited to another book.

Surprisingly, there’s little attention paid to the 11 (!) McCartney albums — three rockers, three live collections, three classical, and two experimental efforts (as the Fireman) — released during the 1990s, or to his three world tours over the period, which included 186 concerts.

Since the 1970s, McCartney’s touring band had included his first wife, Linda, who died in 1999. She was a keyboard player and backup singer who Moores observes started off with virtually no experience but improved with time. One chapter in the book is a thoughtful look at her many influences on Paul, notably how they became vegetarians together and how, in 1991, she launched a hugely successful line of vegetarian frozen foods (now owned by Hain Celestial Group). She and Paul made guest appearances on “The Simpsons” in 1995 in exchange for a promise that Lisa, one of the principal animated characters, would remain a vegetarian forever.

Not much there that most serious fans didn’t already know, which is why a paragraph near the end of the book (right after a bit about Paul’s efforts as a painter) is especially grating:

“While there is not the space to delve into them all here, other out-there activities McCartney got up to in the 1990s included collaborating on a musical adaptation of the poem ‘Ballad of the Skeletons’ (1996) with Beat poet Allan [sic] Ginsberg, resuming his role as a DIY DJ with the creation of a ‘wide-screen radio’ show called Oobu Joobu (1995), making the Liverpool Sound Collage (recorded in 1999-2000 with Super Furry Animals)...and even helping out on ‘Hiroshima Sky Is Always Blue’ (1995) by Yoko Ono.”

There surely could have been space for those less-known stories if fewer off-topic tangents had been taken.

For what it’s worth, some nice black-and-white pictures are scattered throughout, but most are likely to be familiar to anyone who didn’t stumble onto this book by accident.

Randy Cepuch is a member of the Independent’s board of directors and an enthusiastic Beatles fan.