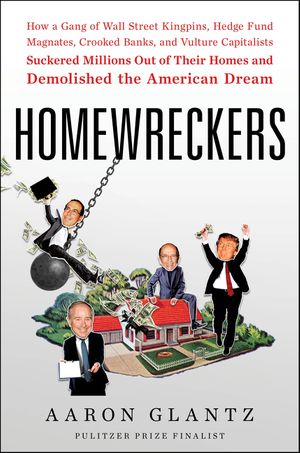

One Day, Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This

- By Omar El Akkad

- Knopf

- 208 pp.

- Reviewed by Sarah Trembath

- March 20, 2025

An astonishing assessment of our coming moral reckoning on Palestine.

Every time I review a book, I ask myself, “Who is this for?” I first wrap my head around its intended audience, and then I can assess how well the book did what it wanted to do. As I got into Omar El Akkad’s One Day, Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This — savoring his gorgeous prose as if each utterance was a delicacy of words, feeling each page as one might feel any other painful thing one needs — it occurred to me: This book is for me. It is a pristine lamentation, a mirror, and — for humanitarian activists of the literary type — an amplification of our cry written by a lauded journalist far more eloquent than most and deeply committed to the sanctity of human life.

One Day is also a call to conscience. It isn’t just for those of us who agree with every word. It is for anyone with the courage to peel back the veil of delusion that enshrouded the West the day it committed to condoning “the world’s first live-streamed genocide” in Palestine. Most Westerners, El Akkad contends, have developed a “terrible immunity” to preventable mass-scale cruelty and have concluded that “certain peoples simply need to be crushed.”

One Day is not for Zionists or die-hard conservatives who truly believe in the crushing; it is not a call to their consciences. They are already morally honest and can say, “At least there’s no contradiction between what I am, what I claim concerns me, and what I plan to do.” El Akkad’s audience, then, is the liberal, the person who knows better than to tacitly condone mass atrocity but has “said nothing” about all the U.S.-sponsored killing and the obvious propaganda about it.

He is refreshingly brutal about such folks. Modern centrists are “transactional,” he writes; the liberal is morally “vacuous.” Middle-of-the road Democrats failed profoundly, committed as they long have been to begging voters to simply “hold their nose and align with the least worst thing” between the two major parties. In fact, in the mainstream Democrat, El Akkad sees “the smirk of someone who has come to realize the ugliness of the enterprise they have passively aligned with but cannot muster the courage to abandon now. The soul, what’s left of it, buckles under the weight of contradiction, and all one can do is hide behind that pained little smirk, the half-stance of the spineless, the chanting, with not quite enough conviction, of four more years, four more years [of Democrats in the White House], as the bodies pile up outside [their] door.”

They have “stepped too far into complicity with something evil” to turn back now.

Such people reflect the neoliberal society in which they thrive, defined by “the gap between its lofty ideals and its bloodstained reality,” wherein the “well-being of Congolese children” does not yet outrank “the desire for evermore powerful smartphones.” But “there’s no such thing as other people’s children,” El Akkad reminds readers. All people’s children are his children, my children, and yours. Thus, the book is a warning to those who have strayed too far from the basic moral truths of the world.

As a journalist, El Akkad has borne witness to a number of atrocities, and he is not impressed with the mainstream press’ jingoistic dismissals of them or the gullibility of their readership. His rhetorical analyses of the media, its “anesthetic euphemisms,” its “equivocations,” its dishonesty, its “trite invectives,” and its “tortured rhetorical constructions” are scathing and revelatory. He shares, for instance, that “When the Israeli military open[ed] fire on starving civilians clambering for flour, The Guardian describe[d] the killings as ‘food aid-related deaths.’” This is “narrative power,” terribly abused.

El Akkad’s critiques of his own once-loved vocation are gut-wrenching. He’s lost the ability to be in the professional spaces that he used to occupy with ease. His dilemma, which many of us are also experiencing, is, “What is this work we do? What are we good for?” He wonders, “What’s wrong with me that I can’t keep living as normal? What is wrong with all these people who can?”

One Day is not without hope, though. After 185 pages of pulling back the veil, El Akkad allows, “It is not so hard to believe, even during the worst of things, that courage is the more potent contagion [than complacency and delusion]. That there are more [people] invested in solidarity than annihilation. Just as it has always been possible to look away, it is always possible to stop looking away.” For, “alongside the ledger of atrocity,” he has kept another, which attests to the best in us:

“The Palestinian doctor who would not abandon his patients, even as the bomb closed in. The Icelandic writer who raised money to get the displaced out of Gaza. The American doctors and nurses who risked their lives to go to treat the wounded in the middle of a killing field. The puppet-maker who, injured and driven from his home, made dolls to entertain the children. The Congresswoman who stood her ground in the face of censure, of constant vitriol, of her own colleagues’ indifference. The protesters, the ones who gave up their privilege, their jobs, who risked something, to speak out. The people who filmed and photographed and documented all this, even as it happened to them, even as they buried their dead.”

What a service it is to give substance to the silhouette of the quiet people of principle whom one can’t really see beyond the warmongers and the deluded or disinterested masses.

This weary activist/writer is grateful for Omar El Akkad and the courage that it took him to dig so deep. I’m grateful to Knopf for publishing this masterpiece, which goes against the official position of our war machine. Both author and publisher are doing a great service. This is because, as awareness seeps in — the “omg, I should have been against that genocide” — many Americans will feel the need for absolution. One Day, Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This will help them get there, gently but unapologetically, setting folks down where they should have been all along.

Sarah Trembath is an Eagles fan from the suburbs of Philadelphia who currently lives in Baltimore with her family. She holds a master’s degree in African American literature and a doctorate in Education Policy and Leadership. She is also a writer on faculty at American University. She reviews books for the Independent, has written extensively for other publications, and, in 2019, was the recipient of the American Studies Association’s Gloria Anzaldúa Award for independent scholars for her social-justice writing and teaching. Her collection of essays is currently in press at Lazuli Literary Group.

.png)