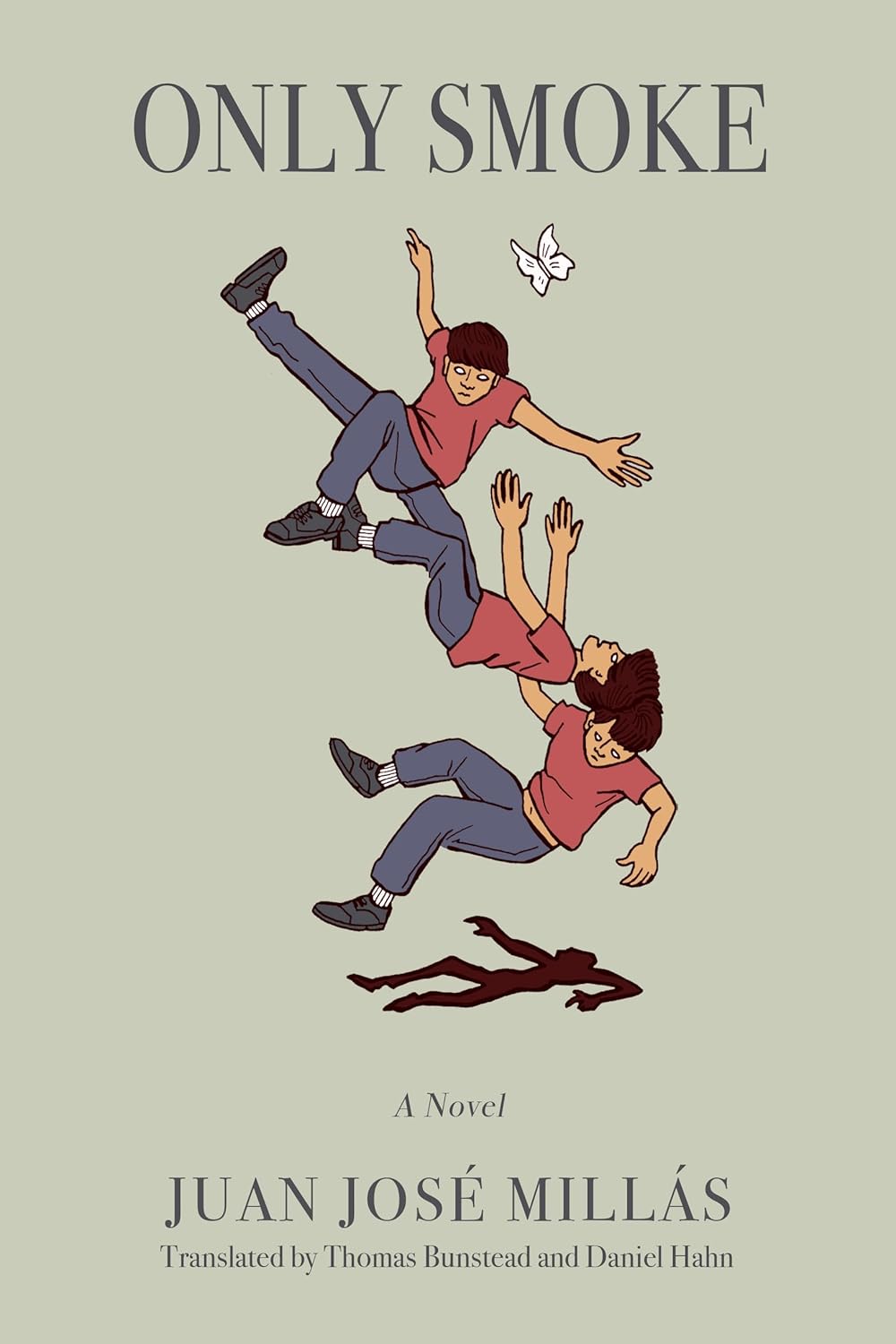

Only Smoke: A Novel

- By Juan José Millás; translated by Thomas Bunstead and Daniel Hahn

- Bellevue Literary Press

- 176 pp.

- Reviewed by Mike Maggio

- May 23, 2025

A young man searches for his father while channeling Grimm’s Fairy Tales.

Imagine a young man abandoned by his father at an early age. Just like his father, his name is Carlos. Now imagine that, when Carlos the son reaches adulthood, Carlos the father dies in a traffic accident, unexpectedly leaving the son all his possessions, including an apartment filled with books.

Carlos the son moves into his new abode and begins wearing his father’s clothes. Then, one night, as he’s getting ready for bed, he finds a copy of Grimm’s Fairy Tales on the nightstand, along with a notebook filled with his father’s scribblings alluding to a girl who seems to be his daughter and who dies at the very moment he’s pinning a butterfly to his bulletin board.

“A troubled man,” Carlos the father’s estranged wife would constantly say of her husband. And yet, here was also a man apparently steeped in literature — steeped in imagination — whom Carlos the son now feels compelled to learn more about.

The tale that unfolds in Only Smoke, by acclaimed Spanish author Juan José Millás, is a blending of reality and fantasy, though it’s not magical realism. The story is written in deceivingly simple prose that resembles the language of fairytales. Carlos the son (these appellations may sound awkward, but they mimic the language of the novel) begins reading Grimm and, like his father before him, gets transported deep inside them, where he finds remnants of the elder Carlos. It is only later, when he discovers a homunculus living in the wall behind his bathroom mirror, that Carlos the son’s true wish is granted: He comes face to face with his deceased parent.

Or does he?

Perhaps this book should’ve been called Only Smoke and Mirrors, for there are parallel universes here, not least of which is the one where Carlos the younger embarks on a journey of discovery not only of his father but of himself. He has, for example, his first sexual encounter — with the very next-door neighbor who supposedly bore his father’s now-deceased daughter.

Unfortunately, this mix of fantasy and reality — of fact and conjecture — sometimes falls flat, often thanks to cumbersome language, as in this scene where Carlos the younger gets trapped inside “Hansel and Gretel”:

The real Carlos, meanwhile, was in the bedroom again with the book in his hands.

“I’m back,” he said to ghost Carlos.

“Yes, I can see,” came his reply.

Though ghost Carlos was not able to sample the house’s sweet flavors for himself, he somehow succeeded in transmitting them to the real Carlos…Ghost Carlos tried to return to the body of the real Carlos, who was fast asleep, but found he wasn’t able to.

And so on, with ghost father and ghost son interacting with their corporeal counterparts. While the blurring-of-the-actual-with-the-fantastical intent here is admirable — it is, in fact, the point — the execution can be clumsy.

At times, Only Smoke feels reminiscent of Luigi Pirandello’s Six Characters in Search of an Author, except, in this case, it’s the characters from one story — the one we’re reading — trying to influence those from another:

“In this place, son, you and I are nonbiological forms of existence. They can’t detect us, but we can still occupy their minds, which is the part of them least rooted in biology.”

“But they don’t exist, either — they’re characters.”

“They exist in the same way you do in the so-called real world. You think people are more real than these characters That’s a dream; it’s a delusion you’d do well to give up as soon as possible.”

And therein lies the crux of the narrative: The line — the smoke — separating the real world from the fictive one is thin; perception is the filter that declares a glass half empty or half full. Whereas an estranged wife sees Carlos the father as “a troubled man,” the son comes to see him as someone with a better grasp on the human condition than your average Carlos on the street.

In some ways, Only Smoke is a disappointment, for it is oftentimes predictable. In others, it is, like most fairytales, thought-provoking in the most simplistic of ways. No doubt, it will leave you pondering the world as we perceive it and wondering if that homunculus behind your bathroom mirror really exists.

Mike Maggio’s latest novel, Woman in the Abbey, was released in February and has been called “a magnificent blending of horror, fantasy, romance and suspense.”