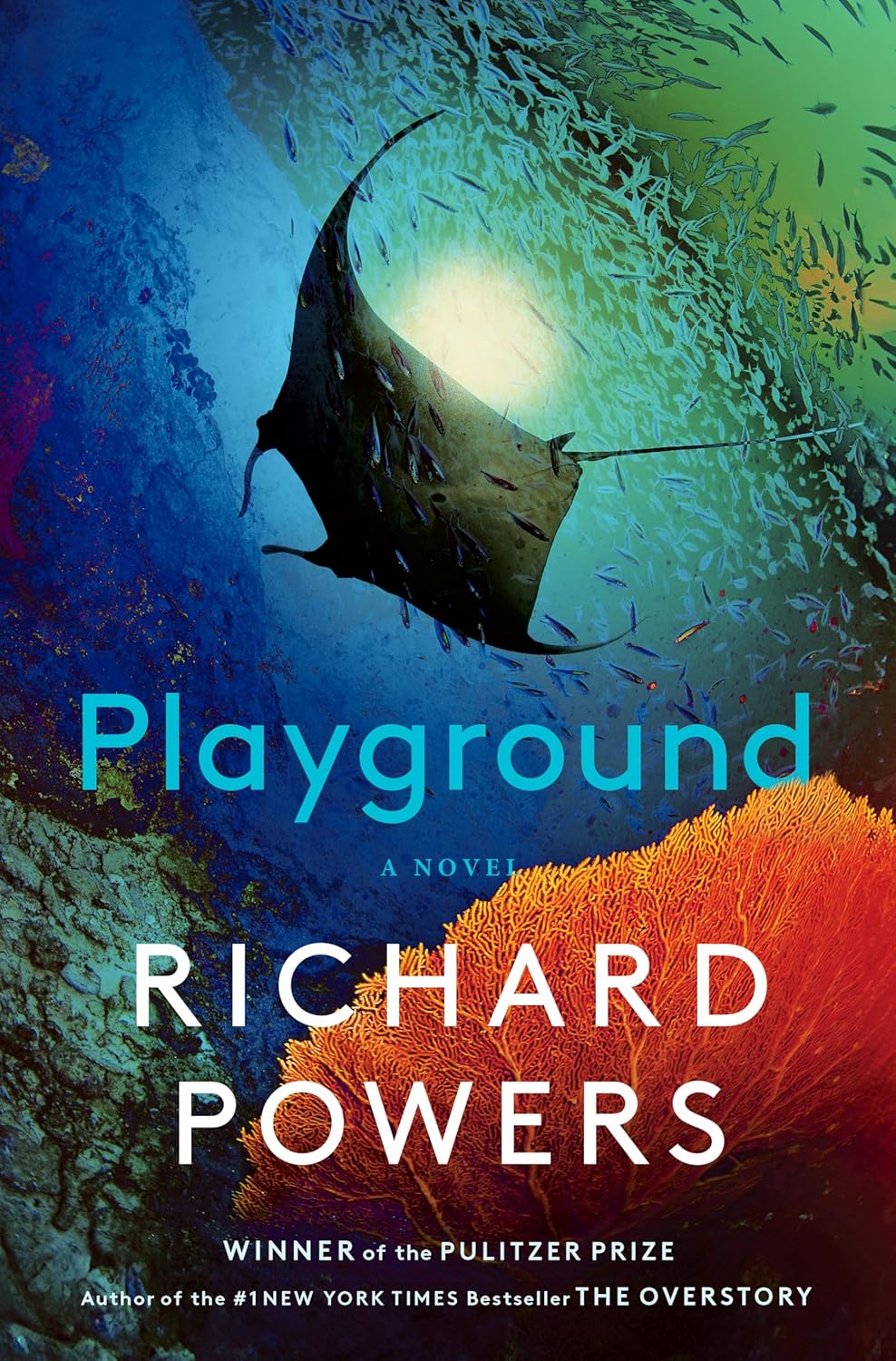

Playground: A Novel

- By Richard Powers

- W.W. Norton & Company

- 400 pp.

- Reviewed by Kristin H. Macomber

- October 2, 2024

A provocative exploration of our depths both interior and oceanic.

For weeks now, I’ve been lugging around my advance copy of Richard Powers’ Playground, devouring chapters in waiting rooms and dog-earing pages on subway rides. When people nearby happen to notice that the book is by the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of The Overstory, they ask what this new novel is about. Where to begin?

Well, as the cover art suggests, there is an “understory” element to Playground, which includes remarkable descriptions of the world that dwells in the depths of our oceans. But it also questions the consequences of allowing human discourse to be overrun by social-media algorithms and generative AI. Oh, and a curious fact: Portions of Playground take place on a real Pacific atoll decimated by phosphorus mining in the mid-1900s and which, in this fictionalized account, is now inhabited by 82 citizens who’ve been called upon to vote yea or nay on their island’s proposed future as a staging zone for launching manmade floating city-states, the better for mega-billionaires to protect their investments and prolong their tenure at the top of the net-worth food chain.

Whew!

Don’t worry, no casual passerby was subjected to that entire hodgepodge of a response. I generally opted for a simpler description: Playground is about a tech whiz, a poet, and an artist — their friendship and love and betrayals and falling outs. It’s also about a deep-sea diver and how she engages a generation to care about the panoply of life in the ocean. And, at the end, it’s about those 80-plus people on that rocky outcropping in the Pacific and how they choose to save their home and their souls.

Playground’s swirling narrative centers around two young men: one brilliant and entitled, the other brilliant and penniless, both suffering from personal lives they’re anxious to escape. They meet in high school and bond over their mutual love of board games — first chess, later Chinese go — along with their parallel desire to outdo one another on all fronts. Over time, they shift from nonstop competition to pursuing their individual interests as they set off on wildly divergent academic paths: poetry and computer science. Once in college, the men befriend a young woman who shrewdly draws them out with a game that requires each to share his innermost truths and dreams.

Drifting through the three students’ storylines is the diver’s thread, which traces her lifelong quest to identify undiscovered aquatic creatures large and small in biozones so amazing and complex, the only way to widely share what she’s witnessed is to write a book targeted at young adults. Her treatise becomes a clarion call to the next generation, urging them to protect the oceans in order to preserve the planet.

How does Powers manage to weave all these strands into a coherent saga? In part, by employing a pair of alternating narrators. The first is a classic third-person-omniscient voice that reveals all and provides useful background intel with Wikipedia-like efficiency. The second, whose presence is announced by a switch to italics, is the internet-obsessed half of Playground’s high-school duo. We learn that he’s become supremely successful in his professional life — think Mark Zuckerberg, only smarter and more creative.

Alas, he is now also supremely unfortunate: Rogue proteins are eating his brain. This fact has lit in him a desire to tell his story before his memories are stolen away — most particularly, his lingering regret over the rift he orchestrated between his dearest friend and the woman they both adored.

As Playground’s threads cohere, a narrative rift, too, reveals itself, pitting prior depictions of certain scenes against updated ones informed by new facts. This unsettling twist sent me back more than once to re-read passages in search of which voice first told me what, and when. It also made me reconsider to whom, exactly, the dying character is speaking. Is it me, the reader? (Spoiler alert: Nope, it’s not, a fact I should’ve realized sooner.)

In the end, it turns out that the omniscient voice…well, I’m not going to tell you how it turns out. Even as I type these words, I find myself grappling with the dual narrators and how they treat the facts as we readers have come to understand them.

Mark Twain said it best: “Never let the truth interfere with a good story.” Powers has adhered to this magnificently, apparently at one of his narrator’s request. We the living are left to wonder what might (actually?) happen next beyond this fictional saga and in our own futures, which we are only now beginning to face.

Kristin H. Macomber is a writer living in Cambridge, MA. No ChatGPT or AI bots were enlisted in the writing of this review.