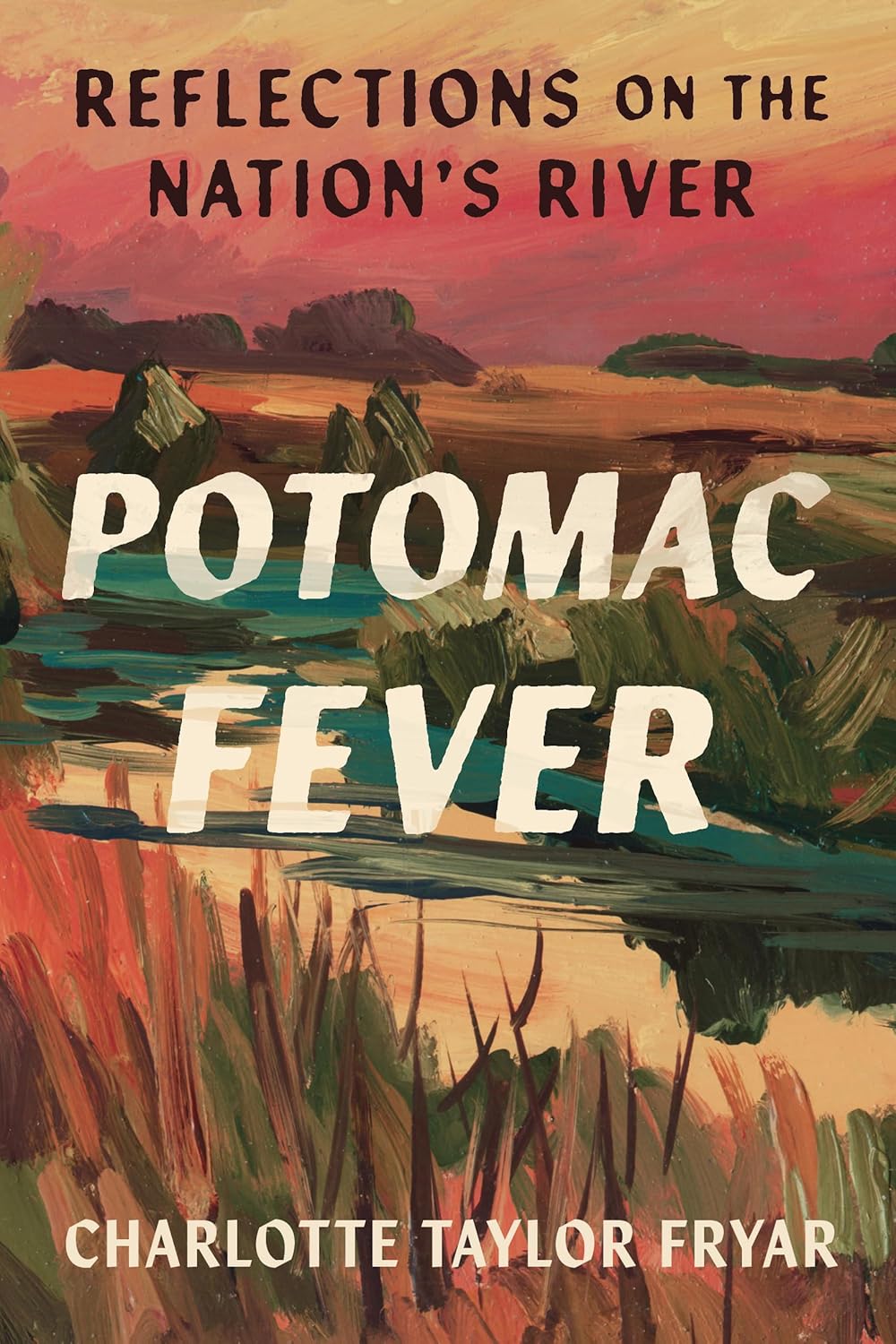

Potomac Fever: Reflections on the Nation’s River

- By Charlotte Taylor Fryar

- Bellevue Literary Press

- 272 pp.

- Reviewed by Chris Rutledge

- April 14, 2025

The DMV’s racist past ripples in its famed waterway.

Potomac Fever is a powerful collection of essays by Charlotte Taylor Fryar, through which she juxtaposes our region’s passion for “America’s River,” the Potomac, with the nation’s history of racism, both environmental and social. While it’s ground others have covered, this work stands head and shoulders above anything else you’ve likely read on the subject.

Fryar’s experience as a writer of magazine pieces and as an herbalist gives her unique insight into how we as people leverage nature, but she takes that experience a step further to explore how we segregate and oppress others. She loves the land but knows that white people have long claimed it, unfairly, for our own purposes.

Potomac Fever is, first of all, a love note to the Washington, DC, region. Fryar takes to the water itself like a lover, sharing how much she endeavors to “walk with the river and even talk to it.” In discussing her excursions to explore the habitat, she adopts a quasi-religious fervor, reporting that “with every year, I find I need this ritual more than I did the last.” She is nourished by her presence in this world.

But Fryar does more, looking at the intersection of racism and the environment and asking the important question, “Who is nature for?” As she notes, the DMV is a “regional ecosystem of intersecting policies, histories, and displacements.” She offers examples of how we white residents have deliberately excluded our Black neighbors from parks, beaches, and other amusements. Such exclusions are not incidental. Fryar tells us that “consumerist and even emotional demands of white people appear to direct many aspects of Black displacement.” White people want what we want when we want it, and a little thing like Black people existing will not stand in our way.

She offers several examples. In the 1900s, beaches were created at the Tidal Basin (something hard to imagine today). Separate facilities and areas were established for white and Black swimmers. However, to some white folks, the mere proximity of Black people was too much to bear. Fryar reports that common myths came to the fore, including “preconceptions about Black people’s predilection to spread communicable diseases.” Simply swimming in the vicinity of Black people could pollute whites. Further, white people came to dwell on “myths of Black male hypersexuality” and were concerned about the virtue of their virginal distaff members.

As is often the case — “White Americans believe deeply that another’s gain is our loss” — whites decided to destroy something rather than share it. The Tidal Basin beaches were shut down by Congress.

This is but one example of whites’ “privatization of public spaces.” Fryar goes into the District’s archives to examine pictures of social activities, and “in every photograph there is also an absence…almost no nonwhite faces.” Americans have historically been determined to secure happiness only for one group.

Beyond recreation, crimes against the DC Black community extend to exposure to pollution. Through efforts to beautify primarily white neighborhoods and provide them access to more pristine nature, trash was rerouted to Black neighborhoods. As a result, “The Kenilworth dump was the worst source of air pollution in the District.” This contributed to lingering health effects for Black residents young and old. “Children developed asthma and adults died young from respiratory illness and strokes,” Fryar reports.

Pollution also extended to the waterways. The Potomac, primarily used by white pleasure-seekers, was cleaned up via concerted efforts late in the 20th century. Unfortunately, human waste had to go somewhere, and that somewhere was the Anacostia River, which bordered DC’s Black communities. The result? “Fecal coliform counts in the Anacostia rose so high…in the mid-1980s that an outbreak of cholera…became a threat.” This would merely be tragic if it wasn’t so clearly criminal.

Even whites who share Fryar’s love of nature have notable blind spots regarding race. For example, Rachel Carson, author of Silent Spring, passionately worked to end the use of DDT and eliminate its impact on the environment. But the very community she sought to serve, Silver Spring, Maryland, was, at the time, a “sundown community,” meaning the only Black people welcome there were servants. Others couldn’t stick around to enjoy nature — they needed to be gone when the last bus left for DC, where they primarily lived and where pollution continued unabated.

Potomac Fever strikes a wonderful balance. In some parts, it is a pastoral, wherein Fryar depicts the wonders of nature found along the banks of our region’s preeminent river. In others, it’s a hard-hitting critique of our racist past and present. We can only hope readers learn from all of it.

Chris Rutledge is a husband, father, writer, nonprofit professional, and community member living in Silver Spring, MD. Besides the Independent, his work has appeared in Kirkus Reviews, American Book Review, and countless intemperate Facebook posts, which will surely get him into trouble one day.