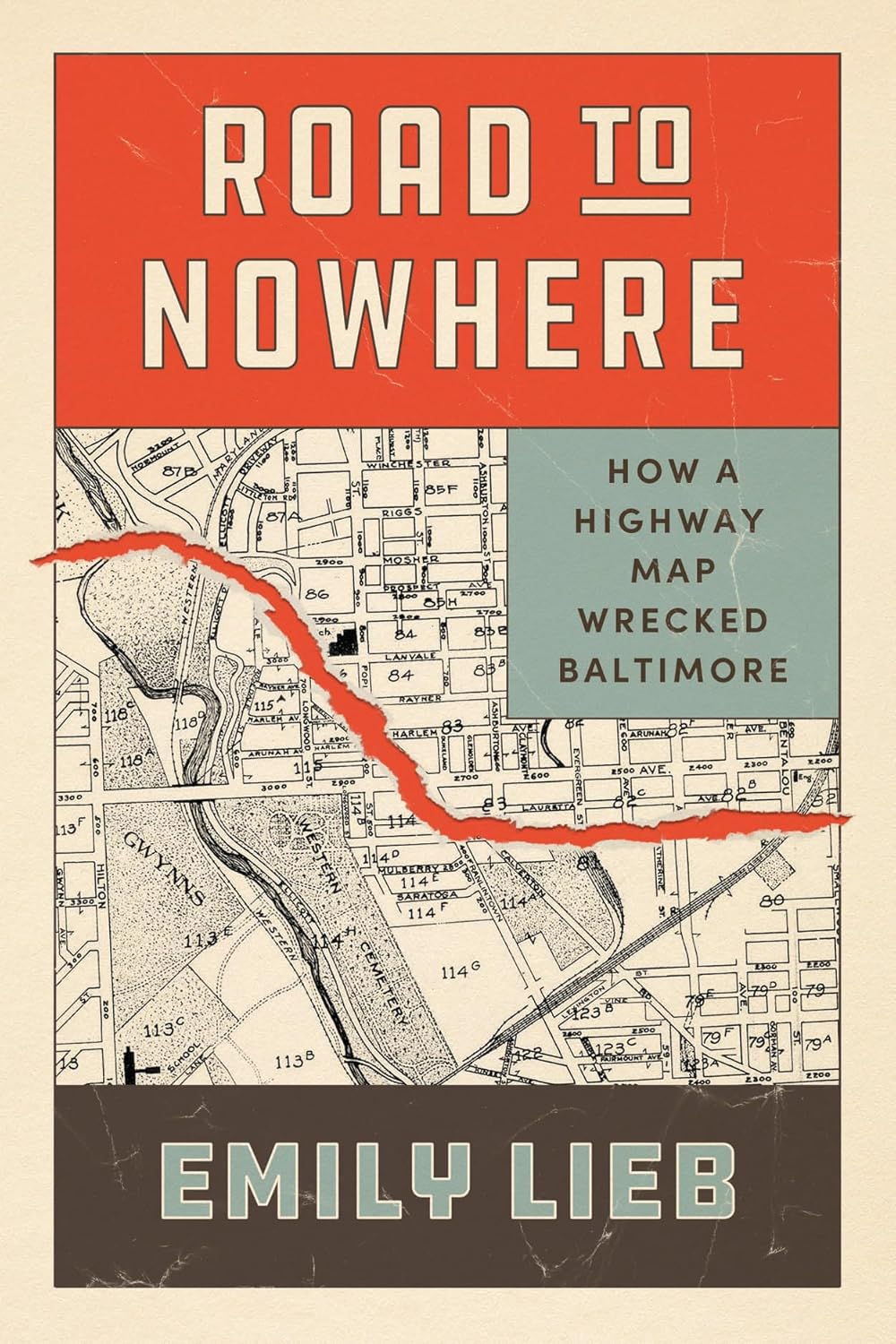

Road to Nowhere: How a Highway Map Wrecked Baltimore

- By Emily Lieb

- University of Chicago Press

- 244 pp.

- Reviewed by Patricia Schultheis

- December 29, 2025

The residents of Charm City’s Rosemont never stood a chance.

For 60 years, this reviewer has lived in Baltimore, a city of neighborhoods, each one distinguished by a unique name, architecture, and history. Emily Lieb’s Road to Nowhere is a detailed tome about one of them: Rosemont. It is also the tale of Rosemont’s near-destruction by callous urban planning, governmental indecision, and political cynicism, plus greed, deceit, and almost unspeakable indifference to the people who actually lived there, people who were just trying to enjoy their share of the American Dream.

On maps, Baltimore resembles a square, with its east, west, and topmost boundaries meeting at right angles. But its lower edges angle downward toward the southeast, with a jagged tear through its center representing the Port of Baltimore.

The port is one of the nation’s busiest and the one on the East Coast nearest the Midwest. For this reason, planners thought Baltimore, long a national transportation hub, was the perfect terminus for I-70, the ribbon of highway first conceived of in the 1950s and planned to stretch from Baltimore to Denver. (For the record, I’ve traveled I-70 as far as the Mississippi River.) Today, the highway stretches 2,100 miles westward past Denver to Cove Fort, Utah, but it doesn’t end at the Port of Baltimore. Instead, it sputters out in a scruff of woodland just beyond I-695 (aka the Baltimore Beltway), the highway encircling the city.

That scruffy patch actually is part of Leakin/Gwynns Falls Park, an extraordinarily large urban park that wanders through West Baltimore (including past Rosemont). Originally, I-70 was to slice through the park, then through Rosemont, across downtown, and through East Baltimore so that cross-country drivers could easily reach their destinations, while suburban commuters could quickly get to work downtown.

Lieb’s impressive research reaches back to when the vast estates of Baltimore’s gentry were converted into neighborhoods like Rosemont, communities of neat rowhouses for white working people. But by 1950 — just about the time the first maps for I-70 were drawn — the city’s demographics were changing: Baltimore’s Black population had risen to 25 percent, and pressure was growing to end redlining, the city’s vicious codified system of housing segregation.

Rosemont’s white homeowners began selling to their Black counterparts, who became much like the homeowners they replaced, forming garden clubs, sending their children to dance lessons, and joining social organizations like the Baltimore Cossocks, dedicated to “wholesome fun and recreation.” In short, Rosemont’s new homeowners were focused on living their lives, while in the halls of power in Annapolis, Maryland, and Washington, DC, highway planners and politicians were churning out map after map for completing I-70.

“Plans came and went, elusive as lynx,” Lieb writes. Just east of Rosemont, several city blocks were condemned, and a scant mile of highway actually was built. Today, it remains a hideous concrete gash going nowhere and serving no purpose other than to lend Lieb her book’s title. Still farther away from Rosemont, the working-class people of East Baltimore found a fearless defender in Barbara Mikulski, a Baltimore City Council firebrand who later became a U.S. senator.

Without Mikulski, the residents of East Baltimore might’ve had their interests dismissed; the residents of Rosemont, lacking a similar champion, had their very humanity dismissed. In 1967, much of Rosemont was condemned, and homeowners were offered “fair market value” for houses they’d spent years making payments on. But who determined that value? Appraisers hired by the same government that condemned the houses in the first place. And if that wasn’t bad enough, the people of Rosemont soon found that getting their houses appraised wasn’t easy.

“I am very anxious to sell and get settled in an apartment. I wrote a letter, and a man came out several months ago but haven’t heard anything since,” wrote one homeowner. Recalled another, “My husband and I have been scanning around for houses; however, it is a dubious situation, not knowing how much we’ll have to spend on a down payment.”

For four years and five months, the people of Rosemont lived with that gut-wrenching uncertainty. After that, matters got worse.

By then, boarded-up houses riddled the neighborhood, and the government hired an incompetent broker to resell them; in a few instances, the same property was sold to more than one buyer. Then, inept contractors bungled essential repairs, and banks granted FHA-insured mortgages to people patently unable to repay them. Eventually, the oil crisis of the 1970s, coupled with the efforts of environmental activists determined to halt a highway slicing through a park, stopped any further construction of I-70. But in Rosemont, the damage was already done.

On a recent afternoon, I drove through the neighborhood, which isn’t far from my former neighborhood of Dickeyville. It was a Saturday, and I saw children playing basketball, a young woman sweeping her front porch, and a man trimming moss from his sidewalk. But I also saw a pile of garbage near overflowing trash cans and boarded-up houses pocking every block. The U.S. Postal Service reports that nearly one-fifth of Rosemont’s residential addresses are unoccupied. The particulars of what happened to Rosemont might not be known by its current residents, but the signs are everywhere.

The Road to Nowhere is part of the University of Chicago Press’ Historical Studies of Urban America series, and it’s as dense as you’d expect an academic tome to be (e.g., it includes more than a thousand citations). Unfortunately, it lacks the deft melding of the personal with the factual in the way that makes Isabel Wilkerson’s similarly erudite The Warmth of Other Suns such a wonderful, illuminating read. Also, Lieb characterizes I-70 as a road for daily commuters rather than the last link in a substantial national highway.

But this is not to say that Road to Nowhere isn’t an important book: It is. With meticulous detail, Lieb illustrates how, for the overworked and under-rewarded people of Rosemont, life became a never-ending shuffle of proposals, plans, and maps. And of how, ultimately, they lost a game they never realized they were playing.

But they are far from alone. Seventeen years ago, on my trip along I-70 through Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois, I stopped in many small towns that had the same atmosphere as Rosemont, the same feeling of having been bypassed and abandoned by unseen, powerful forces. The eyes of their residents held the same wariness of a stranger that I experienced in Rosemont. And their faces evinced the same exhaustion. All across America, people are being pushed down roads to nowhere, with no end in sight.

Shame on us.

Patricia Schultheis is the author of 40 published short stories, including the award-winning collection St. Bart’s Way. She is also the author of Baltimore’s Lexington Market, published in 2007, and A Balanced Life, published in 2018. She has received awards from the Fitzgerald Writers’ Conference, Memoirs Ink, the National League of American Pen Women San Francisco Branch (2010, 2020, 2021), Winning Writers, and Washington Writers’ Publishing House. She lives in Baltimore.