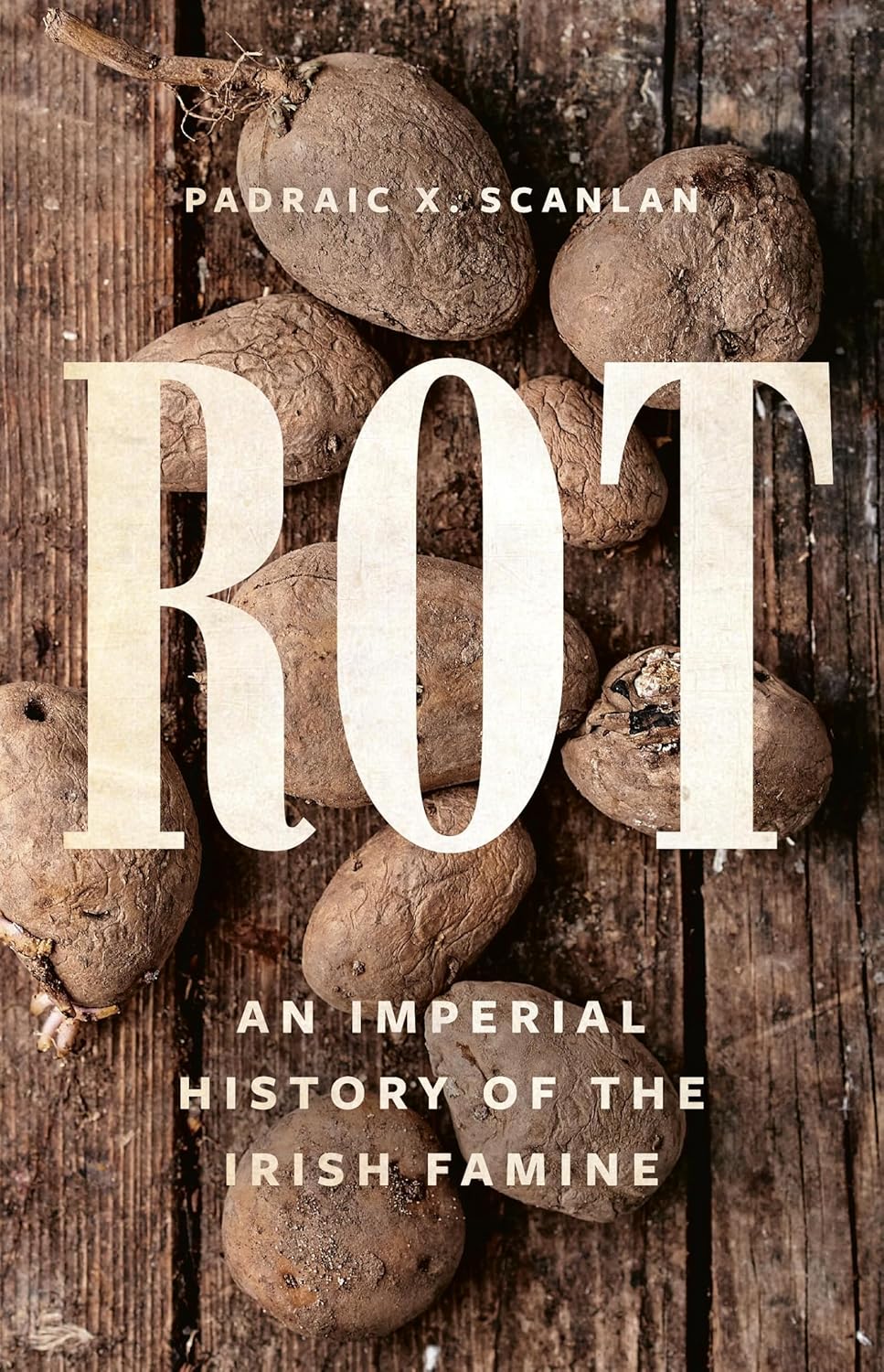

Rot: An Imperial History of the Irish Famine

- By Padraic X. Scanlan

- Basic Books

- 352 pp.

- Reviewed by Bob Duffy

- March 14, 2025

An exceptional account of a crippling, long-ago blight.

Padraic X. Scanlan’s Rot, thoroughly factual and staidly dispassionate, is built-to-order for serious students of European history. It’s a masterful dissection of the origins, advance, and tragic consequences of the Irish Potato Famine, which reached its devasting apogee between 1846 and 1849.

But be prepared. If you’re looking for the story-friendly cushioning of more popularly oriented bestseller candidates, you won’t find that sort of tumble-forward narrative pacing here. Professor Scanlan’s book bristles with facts, statistics, and dogged scholarship — often delivered with raw, firehose intensity but only a modicum of attention to graceful presentation.

By most estimates, the famine left a million Irish dead of starvation (out of a population estimated at 5-7 million). In its aftermath, the pestilence compelled another million and more Irish working people (including every one of this reviewer’s forebears) to leave the country. Their destinations: mainly the U.S., though others set out for Canada, Australia, and England itself.

The responsible pathogen, Phytophthora infestans, arrived in Europe in 1845, likely from Mexico, making landfall in Belgium. It was a “late” agricultural pestilence, meaning the disease it triggered struck when the growing season was well advanced, causing ripe tubers — both in the ground and after harvest — to deliquesce into a black, odiferous, and inedible mush. The disease afflicted potato (and some tomato) crops all over Western Europe.

Ironically, in Ireland, the blight was only marginally more extensive in its reach. But in terms of its human toll, it was far more devasting and intractable there for a welter of sociopolitical reasons. Scanlan brilliantly enumerates the basis and the extent of these tragic outcomes.

To understand the blight’s impact on the Irish populace, we need to reach back to the 17th century, when England’s lord protector, Oliver Cromwell, inflicted a bloody conquest on the Emerald Isle, imposing his final solution on a century of off-and-on conflict between the agrarian Irish and the invading English. The victorious Cromwell redistributed all land in Catholic Ireland among largely Protestant English and Scottish landlords, stripping ownership from the natives.

Many of these newly created landlords were absentee owners, and Irish farmers were forced to rent small plots from them if they wanted to continue raising their potato crops. Over the years, many of these foreign landowners subdivided their demesnes into smaller and smaller parcels, many as tiny as a quarter-acre or less. Meanwhile, the rents demanded per unit of land continued to rise.

You may be surprised to learn that, by the time of the famine, Ireland was no longer an English colony, having been integrated into the newly established United Kingdom in 1801. This occurred with little say from the locals, and with no change in land-ownership policies. And the shoddy treatment — some say persecution — of Irish Catholics continued. Irish folk who cultivated crops, the bulk of the population, were subsistence farmers working tiny plots in thrall to their typically overseas overlords. While arguably corrupt and indisputably inequitable, this imbalance remained in force until the P. infestans plague hit. (Most of Ireland broke away from England in the 1920s.)

So, why the inordinately catastrophic impact of the plague in Ireland? The population, more so than any other European underclass, had become nearly entirely dependent for sustenance on the potatoes they raised. The remarkable productivity and (yes) nutritional content of the crop allowed the people — even on the tiniest of plots — to feed very large families (a source of condescending ridicule by wags across the Irish Sea). Many families could also keep a hog or two and sell off a few piglets every year to pay their steadily rising rents.

But, in 1846, the bottom fell out. Parents and children went homeless, were sent off to workhouses, or starved to death, their corpses rotting in ditch and byway. Alternatively, they could take ship for new lives overseas, with captains charging rock-bottom fares because they could cram the refugees into their holds as ballast cheaper to load and transport than stone.

And the role of the English in these tragic events? Scanlan exhaustively charts the actions of two successive London governments in responding to the disaster, with both falling woefully short, as history testifies. But make no mistake: The response from London was not entirely callous. Some English administrators and politicians — and even some landlords — made heartfelt attempts to improve the lot of the Irish. But for the most part, the official response was a mix of blindly ineffective measures (including those infamous workhouses) and an underlying prejudice against Paddy’s seemingly inherently lazy and drunken habits and his very un-Protestant propensity for wanton procreation.

Professor Scanlan makes the case against British management of the famine with a torrent of brilliantly researched facts. With its stunning wealth of argumentation, Rot delivers a knockout punch.

Bob Duffy, a retired academic and advertising executive/brand consultant, reviews frequently for the Independent.