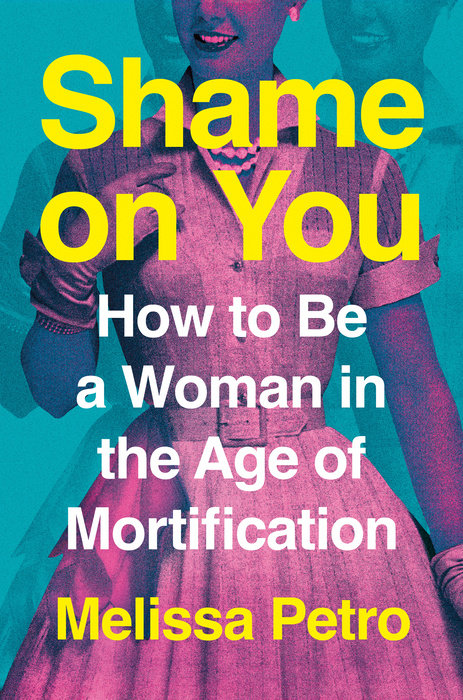

Shame on You: How to Be a Woman in the Age of Mortification

- By Melissa Petro

- G.P. Putnam’s Sons

- 288 pp.

- Reviewed by Yelizaveta P. Renfro

- September 17, 2024

The more things change, the more they stay the same.

Melissa Petro’s Shame on You: How to Be a Woman in the Age of Mortification opens with a moment from her own life when she experienced public humiliation: having to leave her job as a teacher of art and creative writing at an elementary school in the South Bronx after she was outed as a former sex worker. Dubbed a “prosti-teacher” in the tabloids, Petro has spent the two decades since thinking about shame — in particular, women’s shame.

“The fact that women experience shame more frequently, and more intensely, isn’t some biological glitch: it’s the direct result of a patriarchal culture that urges women to feel bad about themselves…and then punishes us when we do,” she writes. Her book, which weaves together research with her own experiences and interviews with hundreds of women, sets out to answer three main questions:

“What are we ashamed of? Where is that shame coming from? What are we doing about it?”

In the first half of the book, “Identifying Shame,” Petro begins by exploring the first question. “Appearance and body image, family and parenting,” she writes, listing common shame triggers. “Money and work. Mental and physical health. Addiction. Sex. Aging. The traumas we survived. The stereotypes we endure. These are the things, according to social scientists, that really set off our shame reflex.”

She tells the stories of women humiliated in the media — Anita Hill, Monica Lewinsky, Lorena Bobbitt, etc. — incorporating data along the way. For example, she identifies the four main responses to shame as fleeing, fighting, fawning, and freezing, and then interweaves her personal story and shame-inducing episodes (stripping, sex work, infidelity, and alcohol abuse, among others). Then, in the second half of the book, “Overcoming Shame,” Petro offers suggestions to help build “shame resilience.”

In other words, this book is part research, part memoir, and part self-help, and in trying to do all of these things, it succeeds in doing each in only a cursory manner.

Much of the latter half of the book reads like pop psychology. “Shame resilience isn’t easy,” Petro writes. “For a lot of us, it means learning to compensate for the failures of adult protection and care. It means learning how to live, mid-life. It isn’t easy, but it’s possible. No matter what you’ve lived through or what age or point in your life, it is possible to recover your sense of self-worth.” In another section, she writes:

“I am on a journey to own my own breath. I am claiming every part of myself and my story, and that means leaving nothing out. What has happened cannot be undone, but it can be dealt with. I am not, and will never be perfect.”

There’s nothing objectionable in Petro’s advice, but much of it consists of vague platitudes. And even her more specific suggestions on dealing with shame — e.g., women need to tell their stories and to cultivate friendships with other women — aren’t especially insightful or novel.

Petro incorporates the voices of other women, including the responses she collected about the shame-inducing messages they’ve internalized. “Society wants us to be this perfect human being: full-time mom, full-time wife, superhero,” one woman tells her. “Men just get to wake up, get ready for work, and come home to a clean house and a hot meal. Women do everything else.” Another woman confides, “I snip, dye, conceal, slice, color, shrink, grow, contour, mutilate, pluck, shave, shave, shave, inject, fill, douse, spray, and starve myself. My value in this world is linked to my desirability…I’m supposed to be lithe, curvy, and beautiful.”

If these laments seem familiar and unoriginal, it’s because they are. Petro’s interactions with women — in interviews, over social media, in casual conversations with friends — reveal that we continue to feel the same pressures we have for decades. Petro herself makes this point when she writes, “Twenty years after Brené Brown declared a war on shame, our culture of shame continues to rage out of control.”

This is a good insight, but what is disappointing about Petro’s project is that while it delivers fresh examples of the problem — such as cancel culture and new channels for shaming courtesy of the internet — it offers no truly innovative perspectives. Rather, it merely rehashes the same conversations we’ve been having all along.

Although Petro synthesizes much of the writing on shame that has appeared in mainstream outlets over the last two decades, other books boast more in-depth treatment of the subject. For instance, Brené Brown’s I Thought It Was Just Me (But It Isn’t) is packed with sound advice on developing shame resilience, and Melissa Febos’ Girlhood is an insightful, nuanced exploration of gender, sexuality, and consent.

Ultimately, Shame on You seems to be taking on too much, and its greatest shortcoming isn’t that any of what Petro writes is objectionable, but rather that it’s all been said before. Though the book is disappointing for this reason, perhaps we should be even more disappointed by the fact that so little seems to have changed for women in the last 20-plus years. We’re still being shamed for all the same old reasons.

Yelizaveta P. Renfro is the author of a book of nonfiction, Xylotheque: Essays, and a collection of short stories, A Catalogue of Everything in the World. Her fiction and nonfiction have appeared in Glimmer Train Stories, Creative Nonfiction, North American Review, Colorado Review, Alaska Quarterly Review, South Dakota Review, Witness, Reader’s Digest, and elsewhere. She holds an MFA from George Mason University and a Ph.D. from the University of Nebraska.