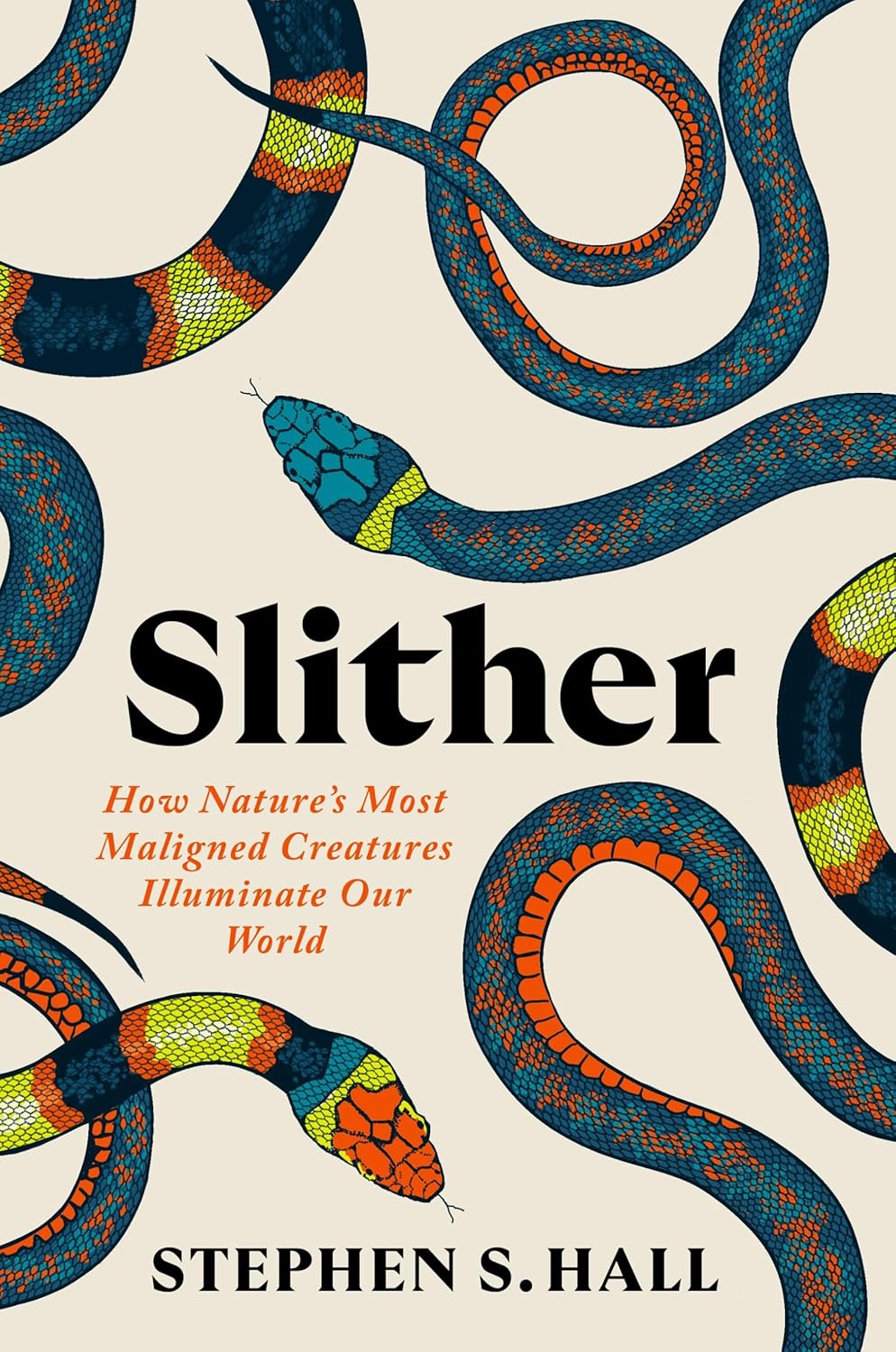

Slither: How Nature’s Most Maligned Creatures Illuminate Our World

- By Stephen S. Hall

- Grand Central Publishing

- 416 pp.

- Reviewed by Mariko Hewer

- June 6, 2025

If not Satan, why Satan-shaped?

Observing the way people cuddle dogs and cats but recoil from snakes — despite all three animals being kept as pets — I’ve often thought that familiarity breeds comfort rather than contempt. It’s not uncommon to hear people opine that reptiles have no personality, no warmth, no sense of companionship, but is that true, or are they simply more alien (and therefore more frightening) than their furry, domesticated counterparts?

In Slither: How Nature’s Most Maligned Creatures Illuminate Our World, Stephen S. Hall makes a compelling case for the individuality, social nature, and fascinating biology of our scalier friends. He explores everything from the mind-bending physics of the sidewinder (“nocturnal denizens of the desert Southwest [who] have a unique form of locomotion that defies logic and compass”) to the complex mechanics of snake reproduction and the explosive phenomenon of the Florida Burmese python. In his introduction, Hall writes:

“Snakes don’t let go of our collective imagination. Of all the creatures on earth, they seem to incite more awe and fear, more earthly fascination and philosophical musing, more veneration and more hatred than any other animal with which humans interact…To the creative imagination, snakes become irresistible metaphoric vehicles to explore human limitation, human fallibility, human mortality, human otherness.”

The author combines high-caliber science writing with detours into the history of serpents in various cultures, peppering each chapter with just plain fun facts. “By some estimates, a dose [of Mojave rattlesnake venom] as small as 15 milligrams — roughly 0.003 teaspoon — can be lethal to an adult human”; “Female snakes can store active sperm for years — up to eight years in one documented case — and essentially self-fertilize at a time of their choosing”; and “Some males, known as she-males, mimic females, manufacturing and emitting female sex pheromones to distract rivals. And some males are so good at this mimicry that they end up courting themselves, endlessly circling and tongue-flicking their own bodies.”

Hall’s writing is captivating and clear, and he touches on broader social conundrums as they abut his serpentine subjects. In a chapter on reproduction, he notes that it took four women scientists to discover and report that female snakes have two clitorises, or hemiclitores, more than a century after a group of men determined that male snakes have two penises (hemipenes).

“It’s fine that it didn’t occur to them, because no one single person can come up with all the questions and all the answers,” says evolutionary biologist Patricia Brennan, one of the team of scientists who published on the clitoral discovery. “What this really illustrates is why diversity in science is important. It becomes a problem if you exclude whole groups of people from being in science, right?”

If there’s a unifying trait among the people portrayed in this book, it’s their reverence for the animals they interact with and their commitment to understanding them better. Harry Greene, a preeminent herpetologist, describes tracking a lethal snake he’d been monitoring for 12 years and searching for her underfoot, only to realize she was hanging “inches from my face” from a branch of the juniper tree under which he was standing.

“She doesn’t rattle,” Greene muses. “She doesn’t pull her head back as if to strike…I think there’s a pretty good chance I missed what would have been a horrible bite, because I had not taught Female 21 that I was a threat.” The author notes that Greene and his collaborator took special care when handling the snakes they were tracking to refrain from using harsh or frightening techniques; Greene believes this made a difference in Female 21’s treatment of him that day and may well have saved his life.

In a world where the decision to be kind and gentle must be made anew each day, it’s refreshing to read Hall’s chronicle of individuals who are choosing to do both. Slither is a triumph of science writing, as well as a boon for anyone who wants to learn more about the not-so-scary critters who crawl among us.

Mariko Hewer is a freelance editor and writer as well as a nursery-school teacher. She is passionate about good books, good food, and good company. Find her occasional insights of varying quality on X and Bluesky at @hapahaiku.