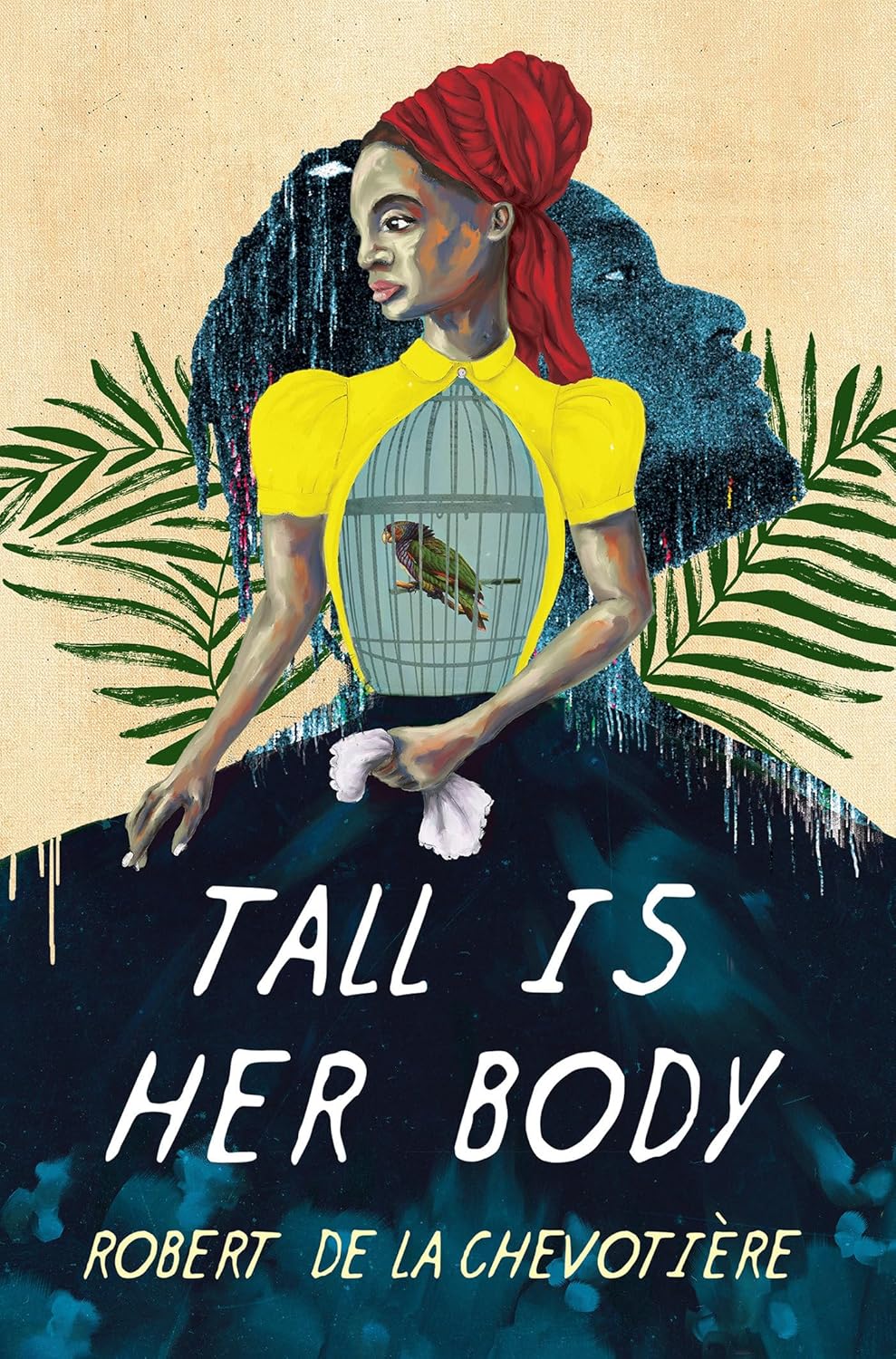

Tall Is Her Body

- By Robert de la Chevotière

- Erewhon Books

- 304 pp.

- Reviewed by Priyanka Champaneri

- November 18, 2025

A Caribbean boy learns to make peace with the living and the dead.

The island chain that runs a curved path from Puerto Rico down to Grenada has provided fertile ground to writers from Jamaica Kincaid to Jean Rhys, and now, with his second novel, Robert de la Chevotière plants his flag. Set primarily in Dominica and Guadeloupe, Tall Is Her Body takes place a decade after the former achieved sovereignty in 1978. It’s a time when the island is still flexing into its identity, pulled between the folkways and beliefs passed down from enslaved ancestors and the legacy of Christianity and colonialism.

Similarly, Fidel, the book’s clear-eyed narrator, is also on a journey to understand his past and decide his future — but his launching point is a brutal one. The book begins with the vicious dispatching of his mother, Florita, and uncle, victims of a double murder at the hands of a mysterious man who’d threatened Florita the day before. Just 6 years old, Fidel is the sole witness and nearly becomes a victim himself.

His orphaning opens avenues to family members he hadn’t been aware of — both at home in Guadeloupe and in neighboring Dominica — all of whom have secrets and stories to tell. Fidel’s confusion is adeptly portrayed by de la Chevotière:

“The only thing I understood at that moment was that my world was no longer just mine. It was getting larger, more occupied — fuller. In turn, I felt smaller.”

The novel’s opening act of violence is the first of many peppering these pages, and each time Fidel gains a certain amount of security, the world tilts. Soon after, he must again find his way with a new home, a new relative, a new set of histories to navigate, and one more thing: a new spirit to acclimate to.

For as he slowly comes to learn, Fidel is Obeah, a conduit with the land who can see the dead as easily as he sees the living. Before long, the ghosts of his mother, his uncle, a grandparent he never met, a childhood friend, and others populate his days. In their random appearances, some are silent and watchful, some repeat inscrutable phrases, and others are vindictive and aflame with the hate they nurtured while alive. Their presence overwhelms Fidel:

“Sometimes I can’t tell the dead from the living. I find myself speaking to people who aren’t there.”

Why do these spirits come to him? What is his responsibility to them? And is being Obeah a gift, as he’s told by some, or is it just a village superstition and not even real? As he comes of age and uncovers more of his family’s history, Fidel is alternately hunted, haunted, and helped by the ghosts he sees.

The central question of what being Obeah means — and whether it’s possible to run away from an ability he never asked for — drives Fidel’s journey from childhood to adulthood. It also takes him from Dominica to Nova Scotia, a place he flees to for college specifically because he hopes the spirits won’t follow him there. “If I wasn’t connected to the place,” he reasons, “perhaps I would not see the dead, or hear them, or feel their wants and fears.”

He mostly succeeds, but while the ghosts are quieter in this colder land, Canada brings its own challenges, including the racism he’s thus far escaped. In exploring what it means to be seen overnight as a minority, and to, in turn, see divisions where none existed before, de la Chevotière is unflinching:

“Where I came from, there was only one Blackness. But in Halifax, I was learning that there were many.”

The book’s swift pace lags in the Nova Scotia scenes, which heavily rely on Fidel’s interactions with characters who are dull and flat compared to the ones he leaves behind in Dominica. But when Fidel returns to his island home, the sparkle returns to the pages. The ghosts come back more readily, too, as if all that’s needed to give them shape are the shared cultural beliefs suffusing the air.

While the bloodshed and loss that drive much of the narrative could’ve become overwhelming, de la Chevotière tempers the voices of the dead with those of the living. With every blow Fidel endures, he also experiences the warmth of friends and strangers alike, their duty born from the simple common bond of humanity. These scenes — of an across-the-way neighbor briefly taking him in and feeding him Eskimo pies; of a family friend chaperoning the scared, lonely child on a boat trip; of an aunt saving teenaged Fidel from school expulsion — are among the novel’s most enduring. If Fidel is sharpened by the violence in his life, he is equally smoothed by the benevolence, a realization he hones as he gets older:

“I sensed that everyone was connected somehow. It’s like the universe was finally connecting all the little dots it had forgotten.”

The pleasure of following Fidel’s journey is in seeing him understand his own role in those connections. As he grows into a man, flees the islands and returns again, looks to (and turns from) his companion ghosts, and forms very real bonds with the living, he is ever the sympathetic character, rendering Tall Is Her Body, which has a vision all its own, an admirable addition to the canon of Afro-Caribbean literature.

Priyanka Champaneri is the author of the novel The City of Good Death.