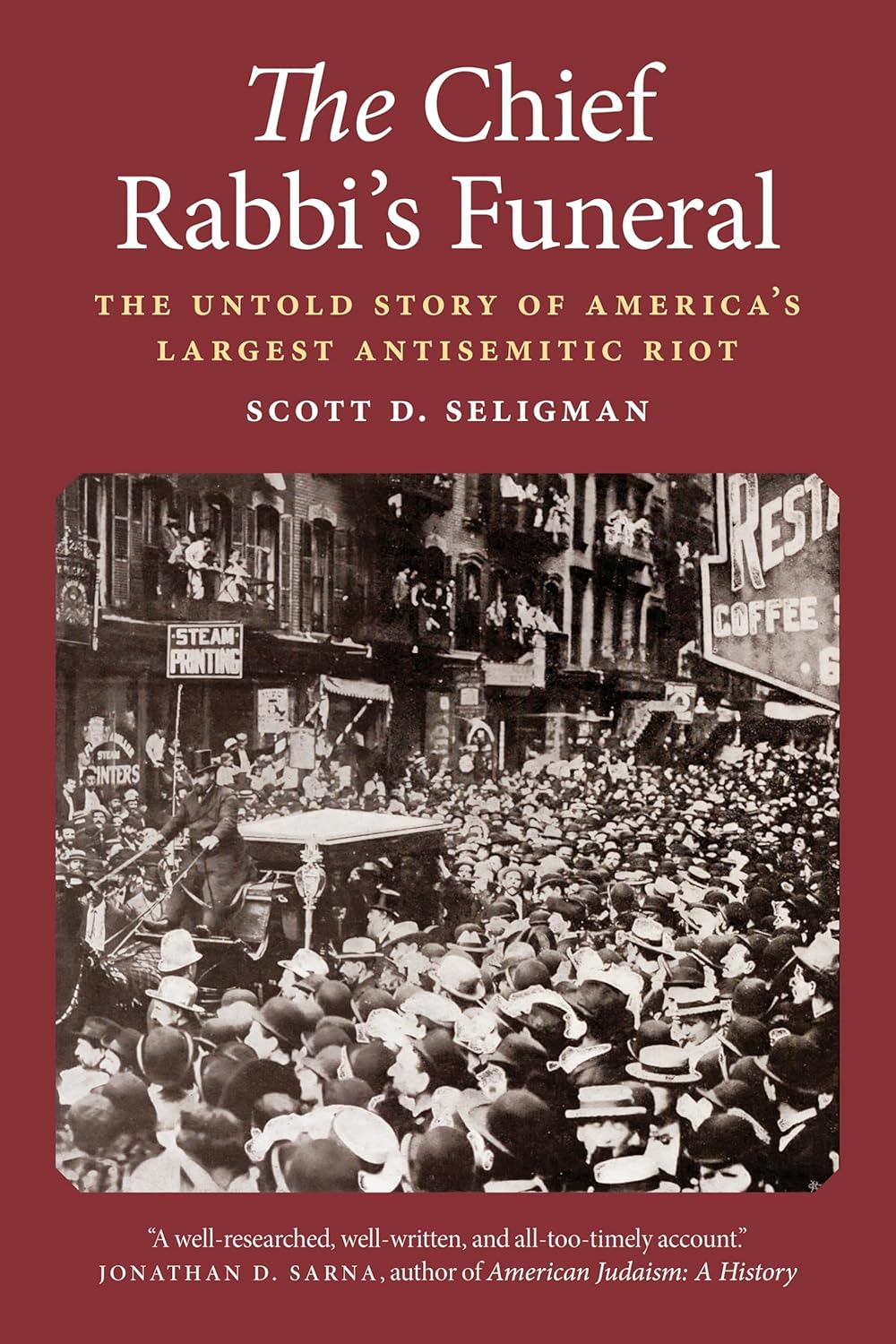

The Chief Rabbi’s Funeral: The Untold Story of America’s Largest Antisemitic Riot

- By Scott D. Seligman

- Potomac Books

- 248 pp.

- Reviewed by Paul D. Pearlstein

- December 16, 2024

When Manhattan’s Jews fought back against Tammany Hall.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, Jews in central Europe could only live in an area ruled by Russia called the Pale. That area is now Belarus, Moldova, parts of Poland, Ukraine, Latvia, Lithuania, and Russia. The Jews there were treated as unwelcome interlopers by the Christian residents. Periodically, they were subjected to violence in the form of state-authorized pogroms and riots. Resistance was impossible, and complaints fell on deaf ears.

The abused Jewish families were extremely poor people scratching out a living in small towns known as shtetls. As conditions worsened, these peasants began to flee the Pale. About 2 million of them arrived in the U.S. between 1900 to 1924. Most of these immigrants were from rural areas and spoke only Yiddish and Russian. They settled in cities at the American ports of entry: New York, Wilmington, Baltimore, Charleston, Savannah, New Orleans, and Los Angeles.

The largest number of Jewish immigrants at that time arrived in New York City and established religious congregations whose members followed strict kosher rules. Meat and fowl had to be prepared by special butchers (called shochets) following the correct methods or it could not be consumed by an observant Jew.

In 1888, a group of Orthodox congregations from Manhattan’s Lower East Side hired Rabbi Jacob Joseph from Lithuania. Along with working as a rabbi, he was to train shochets and rabbis to prepare and certify kosher food, to oversee and protect Jewish education, and to adjudicate disagreements. The congregation titled Joseph the Chief Rabbi of New York. The honorific was pretentious and aspirational at best. While many other countries have or had a “chief rabbi,” there had never been one in the United States. Given congregations’ diversity of practice, only a few shuls and synagogues (orthodox and conservative) but no temples (reformed) accepted him as their chief rabbi.

By 1902, the Big Apple’s Jews were quite diversified. The earliest Jewish settlers were Portuguese, arriving in “New Amsterdam” from Brazil in 1654. They were followed by German Jews. These early immigrants learned to speak English, and many achieved some financial success. The extremely poor, Yiddish-speaking Jews from the Pale who arrived later proved an embarrassment to the old-timers, and their assimilation was slow and difficult.

Rabbi Joseph came to the U.S. with a six-year contract that was not renewed. Considered too old-fashioned for the younger congregants, he never even learned to speak English. Still, he served as a devoted religious leader until his death on July 28, 1902, at age 62. Out of respect, thousands of Lower East Side Jews obtained a police permit and joined in his funeral procession. Tens of thousands of mourners marched through the streets to a ferry, which took them to the burial site in Brooklyn.

Reaching Grant Street, the mourners’ route passed a 200,000-square-foot manufacturing plant, R. Hoe & Company, several of whose employees had a history of antisemitism. As they watched from open windows, the workers began shouting slurs at the marchers. The abuse escalated when some employees started pummeling the mourners with bricks, metal objects, and scalding water.

Dressed in appropriate funeral attire not suited for a street fight, the marchers could do little to defend themselves. They yelled at the Hoe employees, and some threw back the stones and objects hurled at them. A riot soon broke out.

While a few police accompanied the procession, additional forces were called in to help quell the disturbance. Reflecting their own prejudice, the officers only spoke to the Hoe employees, who naturally claimed it was the Jews who started the incident. The cops quickly went after the mourners with their night sticks, beating, clubbing, and making arrests. Several mourners were injured and required medical care and even hospitalization.

The police malfeasance caused immediate outrage in the Jewish community, yet calls for arrests or other action against the Hoe employees were summarily ignored or refused. Clear evidence was disregarded, and no one in authority was reprimanded or held responsible. Corrupt Tammany Hall grandees merely closed ranks and expected the incident to be forgotten.

For many of the marchers — and for the larger Jewish community — the incident was all too familiar. A number of them and their families had witnessed horrible beatings and murders in the Russian pogroms, after all.

With excellent research, author Scott D. Seligman describes in The Chief Rabbi’s Funeral the events leading up to and following the riot. After months of persistent challenges both in and out of court — along with expert lawyering, bold publicity, and growing political clout — things began to change. Supported by a new, non-Tammany mayor and fresh police leadership, the Jews of Lower Manhattan achieved some redress.

The book is cleverly structured for both the casual reader and the serious scholar. A tantalizing preface is followed by a dramatis personae offering a reminder of who’s who. The prologue guides the reader into the main narrative, and a helpful chronology at the end revisits the complex events, dates, and players. Last is a glossary that provides a quick, useful Yiddish lesson on the terms featured in the text.

Beyond chronicling the specific happenings, Seligman emphasizes the significance of the Jewish response to this “American pogrom,” as it marked one of the first times in history that an abused Jewish community stood up and demanded (and achieved) justice. The mourners refused to cower as the pusillanimous, helpless victims they once were. The experience showed them they could have real rights in Di Goldene Medine, their new golden land. But these rights are not guaranteed. They must be demanded, fought for, and earned.

Paul D. Pearlstein is a retired attorney with a student-athlete granddaughter currently sidestepping the campus antisemitism outbreak at UCLA.