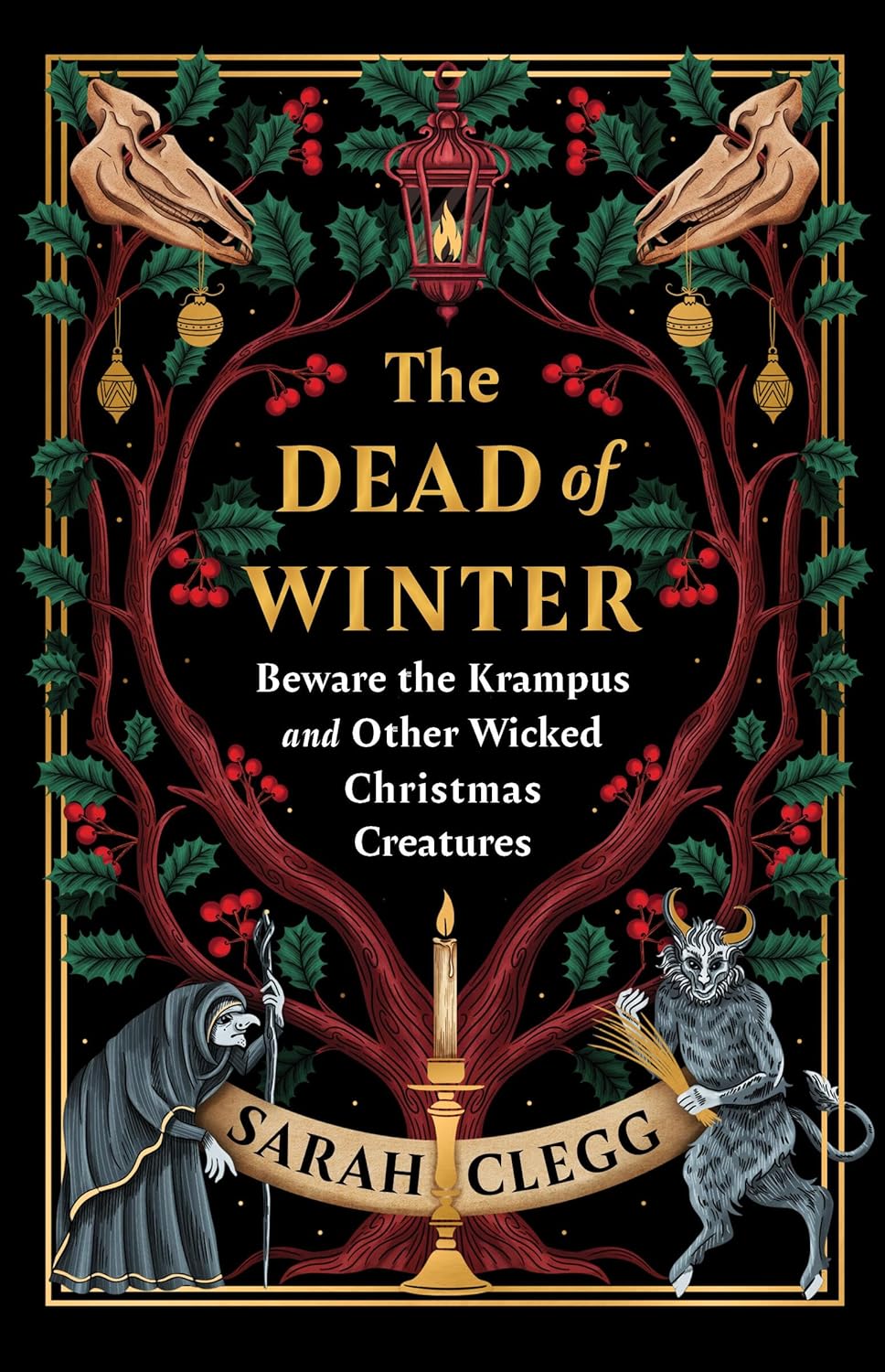

The Dead of Winter: Beware the Krampus and Other Wicked Christmas Creatures

- By Sarah Clegg

- Algonquin Books

- 208 pp.

- Reviewed by Randy Cepuch

- December 4, 2024

A rollicking look at things that go bump in the Yuletide night.

There’s nothing new about the notion of Hallothanksmas. Holiday mash-ups go back a long way and have often mutated (only in part due to the efforts of crafty retailers).

The Dead of Winter: Beware the Krampus and Other Wicked Christmas Creatures explores how a bunch of largely mean-spirited ancient Northern European traditions have somehow turned into today’s harmless Hallmark holidays, while also observing that the darkness of old may be gaining new popularity.

A century or so before anything of note happened in Bethlehem, the Romans began holding a mid-December Saturnalia feast in honor of the god Saturn. It became a weeklong blowout featuring all sorts of bad behavior not unlike that associated with many holiday parties even now — overindulging in food and drink, gambling, crowning of false kings and swapping of social roles, giving gag gifts, public nudity, and even the most inhumane practice of all: forced karaoke.

Back then, there were only 10 months in the year, but the Romans soon added two more (January and February). Before long, the spirit of Saturnalia (and several other winter fetes) had spilled over into the new months as Carnival season, which featured much of the same fun as Saturnalia, as well as going door to door wearing terrifying disguises and making demands, plus some wild parades.

Author Sarah Clegg, a Londoner who earned a Ph.D. in ancient history from Cambridge University, tracked down several present-day incarnations of old rites, reveling in the revels while hopscotching from one holiday horror to another.

While her exhaustive historical and firsthand research is clear, her text only rarely seems academic, and she clearly enjoys cutting loose in the footnotes. In a section describing the Feast of the Holy Innocents (a 15th-century celebration, on December 28th, of King Herod’s massacre of infants in an attempt to kill baby Jesus), the main text mentions a devil with “gun powder burning pipes in his hands and in his ears and in his arse.” Her bottom-of-the-page comment adds, “I’m starting the petition here for school Nativity plays to include fire-farting devils.”

The book opens with Clegg embarking on a Christmas Eve “Year Walk” in rural Sweden — taking a stroll an hour before dawn in hopes of seeing the future. There are strict rules: no talking, no looking into a fire, no eating or drinking. Reputed dangers include losing an eye, losing your mind, and seeing things you don’t want to see (like your own death). But the payoff, in addition to those glimpses ahead, is that getting it right will take care of “any werewolf-based curses you happen to be carrying.” Apparently she does, so no silver bullets are required.

Later adventures find the author in Venice for a costume ball; England for a murderous Mummers Play and the winter Solstice at Stonehenge; Wales to do some wassailing while being spooked by people wearing horse skulls as disguises (and by Morris dancers); Salzburg to mingle with a herd of huge half-human, half-goat Krampus monsters (more than one of whom smacks her with a bundle of grass or sticks, as Krampuses are wont to do); and Finland to meet Christmas witches.

The legends can be convoluted. Consider the contradictory tales of Lucy, a good/bad Yuletide figure in the Nordic countries who is seldom known elsewhere. In one version, Lucy was an angelic young girl who wore a wreath of candles on her head to shed light as she brought food and water to people hiding from religious persecution. Once caught, she was punished by having her eyes gouged out.

In another rendering, an unwelcome suitor who admired Lucy’s beautiful eyes led her to gouge them out herself — and then, each December, to fly through the skies with a posse of unholy souls, stopping at houses to eat food left out for her and her companions. She rewarded those who remembered the milk and cookies; those who didn’t were punished in gruesome ways.

How does one make sense of all that? Clegg observes:

“...only an utter mess of tangling beliefs can lead to a semi-benevolent, disemboweling witch who demands offerings, gives presents, and flies across the land followed by an army of the dead.”

Hard to argue with that.

What about everybody’s hero, Santa? Oddly, he’s considered to be the boss of the Krampuses, although, like many a boss, he can’t really control his charges when they run amok. The main story about him is the one we all know: He brings gifts to good children. What we may not have heard is that, in his earlier days, Mr. Claus allegedly ate bad children and filled his huge sack with to-go meals of the same.

Winter holiday celebrations calmed down considerably in the Victorian era, in part because newly industrialized society left little time for people to misbehave with reckless abandon. Of course, we have modern Christmas monsters on pages and screens: the Grinch, the Elf on the Shelf, Mr. Potter (the mean old man in “It’s a Wonderful Life”), and the Ghosts of Christmas Past, Present, and Future.

Still, this book’s very existence suggests a resurgence of interest in the wilder Yuletide creatures of old, and Clegg offers a reason why:

“Some of this modern embrace of the darker side of Christmas may be a pushback against the saccharine nature of our celebrations — an antidote to the cloyingly twee commercialisation that so many feel the festivities now represent.”

Randy Cepuch is a member of the Independent’s board of directors and a frequent reviewer. His favorite Christmas monster is Jólaköttur the Yule Cat, a giant feline that, according to legend, eats Icelanders who don’t receive new clothes as presents. He is the author of A Weekend with Warren Buffett and Other Shareholder Meeting Adventures (Basic Books, 2007), a business travelogue in which no investors were eaten.