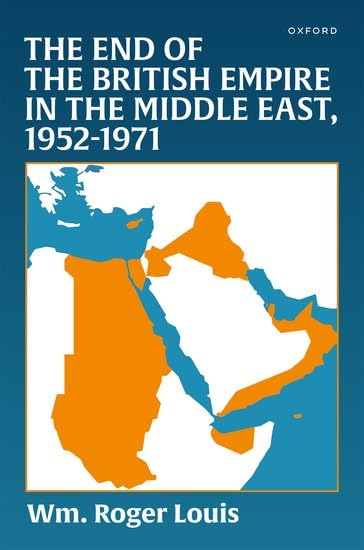

The End of the British Empire in the Middle East, 1952-1971

- By Wm. Roger Louis

- Oxford University Press

- 528 pp.

- Reviewed by Andrew M. Mayer

- July 4, 2025

A stellar assessment of a volatile period in Mideast history.

Wm. Roger Louis, Kerr Chair in English History and Culture Emeritus at the University of Texas at Austin and past president of the American Historical Association, caps a six-decade career in academia with his magnum opus, The End of the British Empire in the Middle East, 1952-1971, a superbly detailed, scholarly study filled with prodigious footnotes from both official and secret files.

“In the background to the present volume, the post-war Labour government hoped to create a new relationship of equal partners with the Arab states and Iran,” the author explains in his introduction. “It would replace the old system of alliances and domination. Caught between the forces of Arab nationalism and American anti-colonialism, the British failed in the quest to transform the basis of their presence in the Middle East.” With that failure came Britain’s eventual exit from the region.

Divided into three sections — “From Musaddiq to Nasser, 1952-March 1956,” “The Suez Crisis,” and “The Middle East, 1957-1971” — the book covers multiple seminal events that unfolded in a relatively brief timespan. Among other clashes, Israel (with help from Britain and France) invaded Egypt during what came to be known as the Suez Crisis of 1956. Later, following renewed unrest, Israel retaliated against Egypt, Jordan, and Syria in 1967’s Six-Day War. Its victory left Jordan with hundreds of thousands of Palestinian refugees (some of whom attempted, unsuccessfully, to overthrow King Hussein in 1970); greatly reduced Egyptian president Nasser’s power; and created the volatile West Bank/Gaza Strip situation, where fighting continues to this day.

Louis, while taking a big-picture view of the region during the Cold War era, does home in on a pair of individuals. “The roles played by two prominent Middle Eastern figures are crucial for understanding the themes of [this] book,” he writes. “One is Mohammed Musaddiq; the other, Gamal Abdel Nasser.” Musaddiq (usually spelled Mosaddegh) was Iran’s prime minister from 1951-1953. Although painted as a demagogue by the West, “Musaddiq worked for social, judicial, and economic reform, including equitable land distribution and taxation,” Louis asserts. “Yet he is remembered above all for his legendary struggle against the British. For their part, the British regarded him as a fanatically anti-British nationalist.”

Musaddiq’s taking over of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (soon to become British Petroleum) set in motion the 1953 coup — orchestrated jointly by the CIA and MI6 — that would topple him. Almost simultaneously, Nasser led an officers’ coup in Egypt that brought down that country’s government. He then nationalized the Suez Canal and pressured the Brits to leave the Canal Zone, thereby precipitating the aforementioned Suez Crisis. “Nasser’s challenge to Western hegemony endured in the history of the region as the quintessential defiance of the British Empire,” writes Louis.

The author also elucidates the causes of — and fallout from — 1958’s Iraqi Revolution; recounts Sudan’s 1956 independence from Britain (which resulted in persistent tension in Aden); explores Yemen’s civil war (and the United Kingdom’s role in it); and chronicles the actions of the U.K.’s various prime ministers during the era, starting with Winston Churchill (in his second term, following his ouster at the end of World War II) and concluding with Edward Heath, who held Britain’s top office from 1970-1974.

Long before the book’s concluding year of 1971, however, the writing was on the wall for British colonizers. Explains Louis:

“The [UN] General Assembly in 1961 created a special committee on colonialism, eventually known as the Committee of 24. Its purpose was explicit: to end all colonialism immediately, which meant the end of the British Empire. Britain’s ethical position, as far as nearly all UN members were concerned, had been shattered as a result of the Suez crisis.”

While he stresses Britain’s crucial participation in the passage of 1967’s infamous UN Security Council Resolution 242 — which guaranteed Israel peace with Arab nations willing to accommodate it, in return for Israel withdrawing from territories claimed in the Six-Day War — a resurgent PLO frustrated attempts at peace as recently as 2000, and the subsequent emergence of Hamas only fueled the fire. Today, Gaza, the West Bank, the Golan Heights, Lebanon, Syria, and Yemen (among others) remain unstable.

Finally, Louis examines the legacy of the Balfour Declaration, signed at the nadir of World War I. The 1917 agreement, known as the British Mandate, guaranteed a Jewish homeland in Palestine while promising that Arabs residing there wouldn’t be displaced. Following the creation of the United Nations in 1945, and with the support of the Truman Administration after the mandate ended, the state of Israel was established in 1948. Shortly thereafter, multiple Arab armies attempted to eliminate it. All were defeated but few have given up.

Professor Louis is to be congratulated for tackling this complicated, ongoing story in the many books he’s written during his long career, including this wonderful volume. It is highly recommended for both scholars and serious students of Britain’s foreign policy in the Middle East.

Andrew M. Mayer is professor emeritus of humanities and history at the College of Staten Island/CUNY.