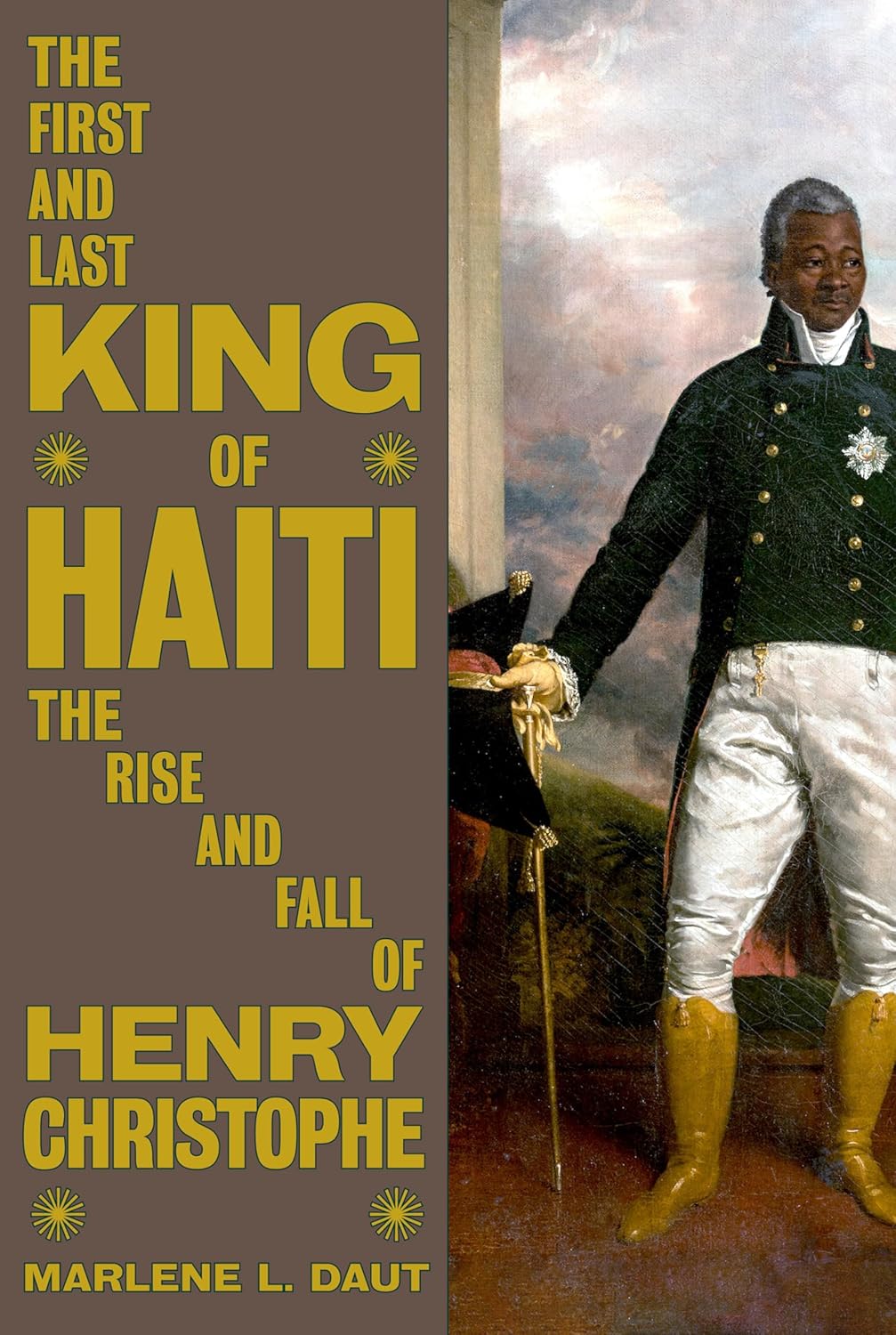

The First and Last King of Haiti: The Rise and Fall of Henry Christophe

- By Marlene L. Daut

- Knopf

- 656 pp.

- Reviewed by Peggy Kurkowski

- January 22, 2025

This revelatory work restores a lost figure to the pantheon of pivotal world leaders.

The Shakespearean drama of Haitian revolutionary Henry Christophe’s life is revealed in all its glorious color and complexity in Marlene L. Daut’s superb The First and Last King of Haiti. A product of more than a decade of research, this stout biography is a shimmering synthesis of his life within the rebellious milieu of Saint-Domingue/Haiti in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

Born a slave on the British-claimed island of Grenada in 1767, Christophe lived an early life that is more shadow than sunlight, standing mostly undocumented. But Daut’s keen instincts for parsing primary sources inspire many “what ifs” about how Christophe came to land in the French colony of Saint-Domingue, where he went from “being a child slave to a child soldier” in the employ of the French military as part of the chasseurs-volontaires, or free men of color who served as soldiers. She cites the amazing fact that Christophe fought at the American Revolutionary War battle of Savannah in 1779, where he would have “celebrated his twelfth birthday either on this bloody battlefield or in the hospital.”

Back in Saint-Domingue, Christophe spent the next decade working at a French luxury hotel before the “enormous freedom uprising” began in August 1791. Here, Daut moves from the murky historical record of Christophe’s early life to the far more substantial documentation of his revolutionary career, arguing that, by 1792:

“Henry Christophe had gone from being an enslaved child to a military officer participating in one of the most momentous struggles for freedom the world has ever seen.”

When, in 1793, slavery in Saint-Domingue was abolished by French decree, Christophe’s visibility as a Black man and French citizen became more prominent within the colony, where he would amass a fortune overseeing plantations on behalf of the French republic. So great were Christophe’s abilities as a soldier and businessman, he earned the trust of Toussaint Louverture, Haiti’s greatest revolutionary leader, who requested Christophe’s promotion to brigadier general. This made Christophe one of only “a handful of Black men…to attain the rank of general in the French military.”

But as with any Shakespearean tragedy, betrayal would soon raise its ugly head. When Louverture moved from arresting and deporting his rivals to ordering the execution of his trusted associate (and nephew) General Hyacinthe Moyse, Daut suggests it was Christophe’s “lifelong instinct of self-preservation” that made him give up on Louverture.

Readers with some familiarity of Haitian history will fare better than the neophyte, as Daut packs a university-level course into these 650+ pages. It is much more than a “biography” of one man in that it ranges widely across Haiti’s early history of slavery, revolution, and transformation under the aegis of first Louverture, then Jean-Jacques Dessalines, and finally, with Christophe’s “crowning” as King Henry in 1811.

A theme that recurs is the question of whether Haiti’s prominent Black and other generals of color were ever truly loyal to France after Louverture’s arrest, banishment, and death, which Daut pinpoints as a key factor that led to an internal rupture with present-day implications:

“Yet one thing is clear: the French successfully sowed division and distrust in the ranks of the Black generals, officers, and soldiers, leading to great divides that persisted in independent Haiti.”

The infighting climaxed with the assassination of Emperor Dessalines in 1806, which launched a civil war between General Alexandre Pétion (the main architect of the emperor’s downfall) and Christophe, Dessalines’ chosen successor. For 13 years, Haiti would have two presidents: Pétion in the south of the island and Christophe in the north. It was Pétion’s feckless agreement with France over the “indemnity” France demanded from Haiti that led to “the greatest heist in history,” Daut contends:

“A recent investigation by The New York Times confirmed that in the end Haiti paid France 112 million francs, or $560 million over more than a century (amounting to between $21 billion and $115 billion in total losses to the Haitian economy).”

Christophe was unequivocally against indemnifying France and “made it his mission to ensure the Haitian people would never forget the basic fact of France’s obsession with enslaving them,” be it by violent force or the imposition of crushing debt. In the wake of a debilitating stroke in 1820, a despondent Christophe chose to end his life, forever leaving an answerless “what if”: What if he had lived?

Peggy Kurkowski is a professional copywriter for a higher-education IT nonprofit association by day and major history nerd at night. She writes for multiple book review publications, including Publishers Weekly, Library Journal, BookBrowse Review, Historical Novels Review, Open Letters Review, Shelf Awareness, and the Independent. She hosts her own YouTube channel, “The History Shelf,” where she features and reviews history books (new and old), as well as a variety of fiction. She lives in Colorado with her partner (quite possibly the funniest Irish woman alive) and four adorable, ridiculous dogs.