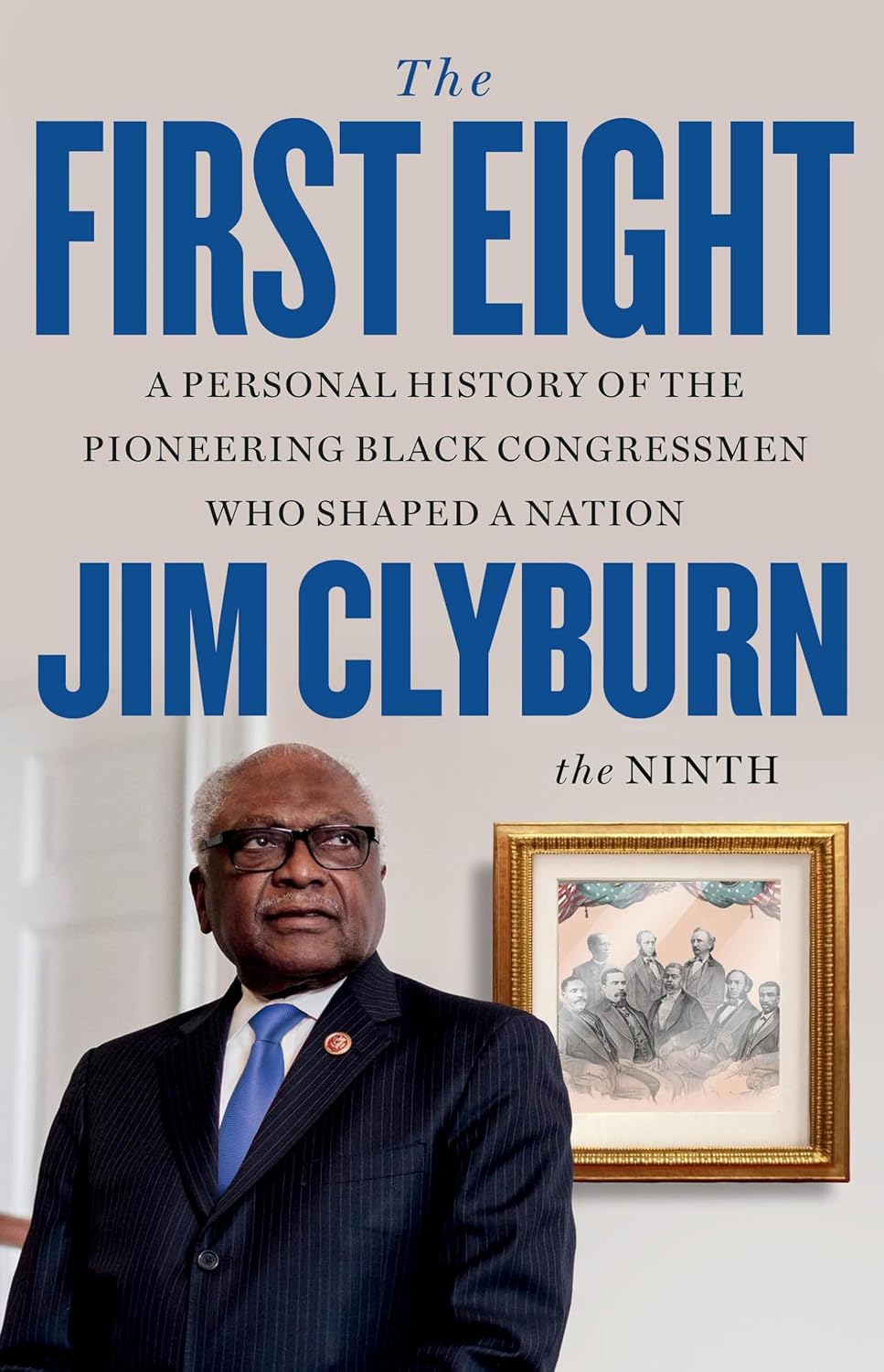

The First Eight: A Personal History of the Pioneering Black Congressmen Who Shaped a Nation

- By Jim Clyburn (the Ninth)

- Little, Brown and Company

- 304 pp.

- Reviewed by Kitty Kelley

- November 10, 2025

The esteemed South Carolina lawmaker honors his predecessors.

South Carolina is the state that gave rise to the Civil War. Three days after Abraham Lincoln was elected president, its legislature passed a resolution calling his election “a Hostile Act” because he was against enslavement. Weeks later, South Carolina seceded from the Union, followed by 11 more Southern states that then formed a rebel government, declaring itself the Confederate States of America and triggering the war.

After four bloody years and 700,000+ deaths, the Confederacy surrendered. More than 4 million enslaved people were set free, and Reconstruction began (despite “Black Codes” enacted to limit the rights of those freed). Since then, 153 African Americans have served in the U.S. House of Representatives, including nine from South Carolina, giving rise to this book, The First Eight: A Personal History of the Pioneering Black Congressmen Who Shaped a Nation by Jim Clyburn (the ninth).

The Sixth Congressional District is the only bit of Democratic blue sky peeking through in the Republican red Palmetto State, and it’s represented by James Enos Clyburn, dean of the state’s congressional delegation. Clyburn is the first Black man to represent his state in Congress since 1897. He’s been reelected every term since 1992 and served as majority whip under Speaker Nancy Pelosi. He became a presidential power broker in 2020 when he endorsed Joe Biden in South Carolina’s Democratic primary, giving Biden the momentum to capture the nomination and later win the presidency. Biden rewarded Clyburn in 2024 with the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Now, the congressman is celebrating himself, his predecessors, and their shared history in a tribute to the African Americans who fought so hard for equality against racial injustice. In honor of the movement to “Say Their Names,” here are the first eight African Americans to represent South Carolina in the United States Congress:

- Joseph H. Rainey (1832-1887), born enslaved, became the first Black member of the U.S. House of Representatives and was the longest-serving Black member of Congress in the 19th century.

- Robert C. De Large (1842-1874) was “mulatto elite,” wealthy, and a slaveholder himself who moved to Charleston for an education despite laws against teaching Black people to read and write. De Large was considered “Brown” and accorded privileges not available to Blacks, earning him no respect from his colleagues — and little from Clyburn.

- Robert Brown Elliott (1842-1884), a Northerner, didn’t grow up in an enslaved state but moved to South Carolina as an adult and a free man. He co-founded the nation’s first-known Black law firm in Charleston and married into a prominent mixed-race family, which put him squarely among the Black elite of the day.

- Richard H. Cain (1825-1887), another Northerner who moved to South Carolina as an adult and a free man, became the first Black minister to serve in Congress. Cain personified the faith that sustained the Black community through the dark centuries of slavery. As Clyburn writes: “Faith is a through line in American history, particularly in the Black community.” Throughout the book, he celebrates the church as a pillar of that community, particularly the A.M.E. Church known as Mother Emmanuel, established in Charleston in 1818. (Clyburn also applauds Cain for purchasing and running a small newspaper to educate and inform his community, which is something Clyburn did for several years before being elected to Congress. He continues to write columns in 200 Black newspapers across the country “to make sure our message gets through the fractured and polarized media landscape today.”)

- Alonzo J. Ransier (1834-1882), the first of two Black lieutenant governors of South Carolina, served only one term in the House of Representatives yet made himself heard: “We are circumscribed within the narrowest possible limits on every hand, disowned, spit upon, and outraged in a thousand ways.” Defeated for re-election, Ransier returned to Charleston and worked as a day laborer for the city until his death.

- Robert Smalls (1839-1915) was a Civil War hero whom Clyburn describes as “the most consequential South Carolinian who ever lived.” While working on a Charleston ship during the war, Smalls plotted an escape when his white supervisors went ashore for a night of drinking, leaving the vessel unattended. During those hours, Smalls commandeered the ship and steered its enslaved crew and their wives into Union waters. “I thought this ship might be of use to Uncle Abe,” he told the Union blockade commander who boarded the stolen steamer. Harper’s Weekly heralded Smalls’ act as “one of the most daring and heroic adventures since the war commenced.” Smalls was summoned to meet President Lincoln, and when “Uncle Abe” asked why he’d dared such an escape, the young man simply said, “Freedom.”

- Thomas E. Miller (1849-1938) studied law at the newly integrated University of South Carolina and became the first president of what is now South Carolina State University. He “was biologically white” but adopted by free Black parents. He asked that his gravestone be inscribed: “Not having loved the White less, but having felt the Negro needed me more.” Inspired by this, Clyburn instructed his own family to one day inscribe on his gravestone: “He did his best to make the greatness of America accessible and affordable to all.”

- George W. Murray (1853-1926), born enslaved and “of darkest hue,” became an emancipated orphan and taught public school for 15 years while tending to his farm and livestock. He was the last Black South Carolinian to serve in the House of Representatives in the 19th century.

While this appears to be a staff-written book, it’s been read and annotated by Clyburn, whose 2014 memoir was entitled Blessed Experiences: Genuinely Southern, Proudly Black. A decade later, the congressman still stands “Genuinely Southern, Proudly Black” as he gives to his constituents their magnificent history.

Kitty Kelley is the author of seven number-one New York Times bestseller biographies, including Nancy Reagan, Jackie Oh!, and Elizabeth Taylor: The Last Star. She is on the board of the Independent and is a recipient of the PEN Oakland/Gary Webb Anti-Censorship Award. In 2023, she was honored with the Biographers International Organization’s BIO Award, which is given annually to a writer who has made major contributions to the advancement of the art and craft of biography.