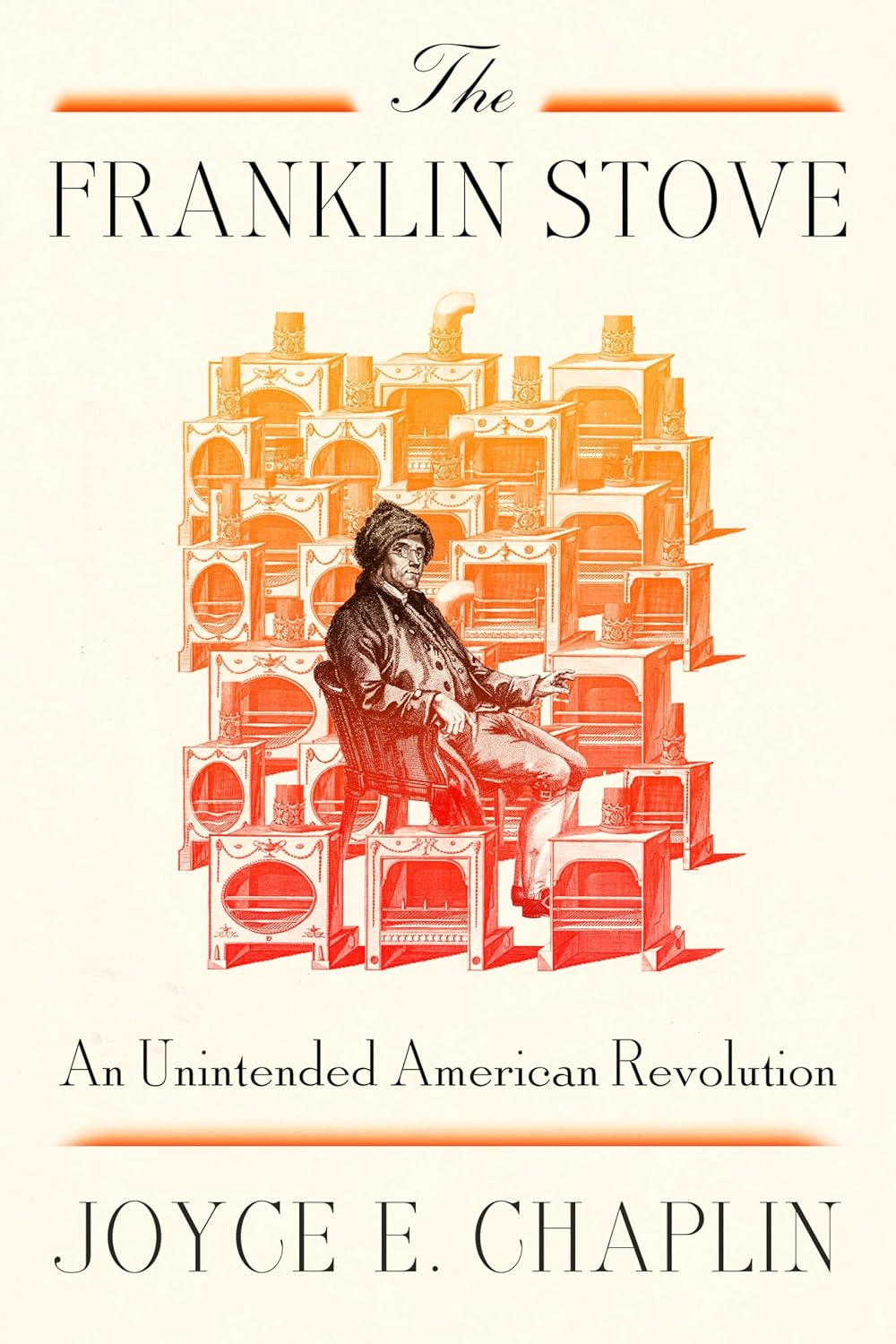

The Franklin Stove: An Unintended American Revolution

- By Joyce E. Chaplin

- Farrar, Straus and Giroux

- 432 pp.

- Reviewed by Stephen Case

- April 22, 2025

This excellent history covers far more than the Founder’s forays into home heating.

Benjamin Franklin’s “stoves” — meant for heating, not cooking — were heavy cast-iron contraptions about the “size of a side table,” writes Joyce E. Chaplin. Burning fewer logs than other devices, they boasted ingeniously located metal plates that channeled the fire to radiate more heat and expel smoke more efficiently than other woodstoves.

Harvard history professor Chaplin, a superb scholar, has written in The Franklin Stove a reader-friendly, fact-packed, and meaty book. It addresses numerous intriguing and complex sociopolitical, geopolitical, and scientific factors surrounding Franklin’s thinking and his invention, including climate, deforestation, and slavery. Drawing extensively from the man’s papers, Chaplin also reveals what an amazing and witty polymath he was, despite his flaws.

To the vexation of Young Man Franklin, the Little Ice Age raged during his lifetime, driving down temperatures while simultaneously driving up the cost to deal with them. He lamented in November 1732 that “Wood is risen to an excessive Price [because] No Vessels can go up or down [the frozen Delaware River], a Thing rarely happening so early in the Year.”

On their arrival, the first European settlers in Pennsylvania met, said Franklin, an “Ocean of Woods.” However, as time passed, forestland disappeared. Why? Endless demand for fuel. By Franklin’s time, cheap timber near Philadelphia “was vanishing,” writes Chaplin, necessitating — and making more expensive — the shipping in of firewood. Compounding the problem was the “constant removal of trees” for lucrative grain-exporting, which required “appropriation of Indigenous land for farming.”

Even though he pined (pardon the pun) for low-priced firewood, Franklin favored deforestation, stating that he “hoped that ‘White People’ would increase and continue Scouring our Planet, by Clearing America of Woods.” In a pamphlet about his stoves, he said he developed them so that “fighting frigid winters could be achieved while [still] conserving trees.” If wood was a precious natural resource, at least his stoves burned less of it.

Understandably, the natives detested the loss of timber. Indigenous Lenape (or Delaware) tribes respected and needed the forests. They “appreciated trees,” explains Chaplin. “They considered them kin, comparable to humans.” And brutal winters didn’t bother them. Unaccustomed to living in heated homes, the tribes saw cold weather “as the time of plenty,” when hungry game exposed itself during daylight, making hunting easier.

Predictably, white settlers and Indigenous people did not mix well, and Franklin, like most of his brethren, harbored deep prejudice. In 1755, writes Chaplin, he brazenly:

“stated his preference for people he deemed white (Northern Europeans…) worrying that globally they were vastly outnumbered by those who were ‘black’ (Africans) or ‘tawny’ (Asians and Native Americans) or ‘swarthy’ (Southern or Eastern Europeans). He complained that [slaves] from Africa had ‘blacken’d half America’ even as some ‘tawny’ Natives remained.”

Too often, conflicts between newcomer Europeans and long-extant tribes broke out into cheating, violence, and subterfuge. Among other incidents she highlights to flesh out the character of the era, Chaplin reports on the “nefarious land grab” of 1736’s so-called Walking Purchase; the 1763 terrorist attack by “vigilante[s] called the Paxton Boys [who] murdered nineteen Susquehannocks” living peaceably in their own community; the assassination of Delaware chief Teedyuscung; and the despicable British colonel Henry Bouquet, who, in 1765, gave smallpox-infected “gift” blankets to Indigenous people.

Getting back to the stoves of the book’s title, their fabrication required the manufacturing of heavy metal plates from iron ore — a need that colonial Pennsylvania’s iron industry could meet ably if not nobly. “[M]aking iron depended on white and Black workers…waged workers, skilled and contracted services, casual labor, indentured servants, convicts and enslaved people.” After 1725, “up to half of the people at some Pennsylvania ironworks were enslaved.”

Although he, too, owned slaves as a young man, Franklin would preside over an abolitionist society as an old one. Even so, states Chaplin, “Most colonial American iron artifacts now displayed in museums should disclose they were ‘Made by Slaves.’”

Over the course of 35 or so years, Franklin would design five versions of his eponymous stove, including one that burned coal to accommodate changing habits in England. (After 1757, he lived mostly in London or Paris.) They all worked well, attracted imitators, advanced home-heating technology, and occasionally irritated their creator. Observing the effects of burning coal, Franklin “complained…about the constant smog.” Yes, his stoves diminished the flow of woodsmoke into homes, but the gentleman scientist’s contraption, alas, proved unable to reduce air pollution overall.

Stephen Case is a member of the Independent’s board of directors and serves as its treasurer.